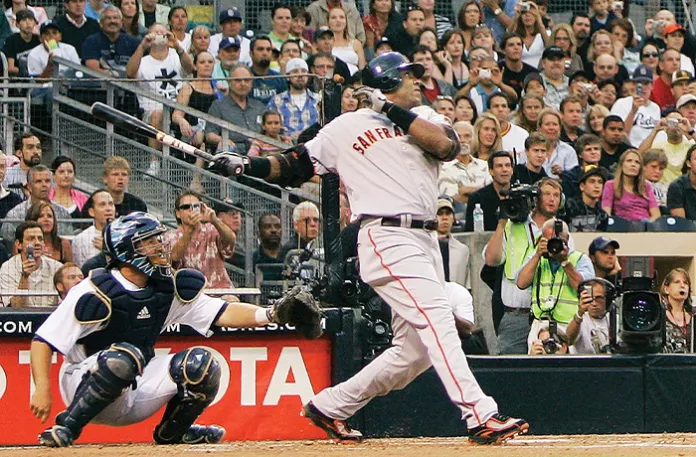

Around the turn of the new millennium, the San Francisco Giants fielded an all-time great baseball player who was so good that fans would buy tickets just to see him play. He would accomplish feats that had previously seemed impossible, and he seemed destined to be a Hall of Famer. They also had Jeff Kent.

Yet, on Sunday, the latter was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, while the former, Barry Bonds, was yet again snubbed.

Kent was a perfectly good baseball player who had an entirely reasonable case for being inducted. But his election at the same time that Bonds was overlooked just draws more attention to the gaping hole in baseball’s Pantheon. Bonds was an alleged steroid user, as was Roger Clemens, the all-time great pitcher who was once again snubbed this year. Each has a resume on the field that, officially, otherwise leaves him unquestionably worthy of induction. But both have been blackballed along with a long list of others who have admitted to using steroids or have been disciplined for failing a steroid test.

There are long debates about whether steroid use should be excused to some extent during the era when Major League Baseball turned a blind eye to it. Should it only be worthy of explicit sanction after it was deemed an offense worthy of suspension by the league? Is even the slightest link to performance-enhancing drugs enough to bar a player from entry into Cooperstown? But the more challenging question is what it says about history and how a uniquely American institution tells the story of a uniquely American sport.

The Hall of Fame isn’t intended to be a roster of Boy Scouts and role models. The players inducted are by no means supposed to be the most virtuous human beings to have ever played professional baseball. The first Commissioner of Baseball, Kennesaw Mountain Landis (who is both a Hall of Famer and very much not a role model), campaigned for a player named Eddie Grant to be inducted. Grant was an undistinguished backup in the early 20th century whose career would have been of little note, save for the fact that he died heroically in combat in World War I. This was not enough for him to even come close to winning an election to the Hall. Instead, the bronze plaques in Cooperstown hold their fair share of racists, drunkards, and even wife beaters. Their Hall-of-Fame worthiness was judged by what they did on the diamond.

The only true sin was being involved in gambling on the sport, since that was an attack on the very integrity of the game. It’s for that offense that Pete Rose, the all-time leader in hits, has long been excluded. But Rose was an outlier. For the steroid era players, there are as many as a dozen excluded as a matter of course. Some of the game’s greatest stars over a period of decades are seemingly barred from entry. These include Bonds, the sport’s leading home run hitter, and Clemens, who is second all-time in strikeouts, along with a long list of players who would actually be recognizable to the average American, such as Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Alex Rodriguez.

The result is that some of baseball’s most memorable players and the holders of some of its most important records are left out in the cold. It is an incomplete and uncomfortable accounting of the game’s history and remembrance of its key figures. After all, a Baseball Hall of Fame with Kent but not Bonds is like a superhero hall of fame with Robin but not Batman.

Major League Baseball is no longer in the wild west of the 1990s, when the league turned a blind eye to the use of steroids. But this is not a problem that will go away as fans who grew up watching players from the steroid era become geriatric millennials and, eventually, geriatrics.

NBA SCANDALS LEAD TO SAFE BET ACT FULL-COURT PRESS

These days, a handful of players still get caught using performance-enhancing drugs every year. In 2022, Fernando Tatis Jr., a star player for the San Diego Padres, served an 80-game suspension after failing a drug test. It’s certainly reasonable to think players such as Tatis, who were caught red-handed during a period when steroid use is rare and severely sanctioned by the league, should never be so much as considered for the Hall. But a significant percentage of an entire generation of baseball greats are in a different, and more ethically gray category — unproven but believable steroid allegations, or they were caught during a time when it was common and part of their professional culture. Should they be out of the running forever?

That’s a choice that the sport needs to reckon with explicitly after decades of hoping the problem somehow goes away until the time rolls around again for Hall of Fame announcements. Then we are once again faced with the question of whether we want an expansive Hall of Fame with tainted immortals, or a constricted one that excludes some of the game’s greatest players.

Ben Jacobs is a political reporter in Washington, D.C.