The Netflix series Death by Lightning offers a compelling, dramatic look at James Garfield‘s rise to the presidency. It also explores the journey of Charles Guiteau, the man who assassinated Garfield when the newly elected president refused to give him a job in the administration under the “spoils system” that took shape over the previous 50 years.

Garfield, who likely would have survived his wounds today, died 79 days after he was shot, not from the wound itself but from infections and sepsis caused by doctors constantly probing his body searching for the bullet. Despite his brief time in office, Garfield challenged the spoils system and another form of patronage in the federal government, “Senate courtesy.”

The spoils system and Senate courtesy became so ingrained in the federal government that they almost seemed routine, despite the system’s tendency toward political favoritism and outright corruption. It started under President Andrew Jackson in 1829. After his election, he replaced a large number of federal bureau chiefs, marshals, attorneys, and other officials with party loyalists. Sen. William Marcy of New York is credited with coining the phrase often used in various contexts when defending Jackson, saying, “to the victor belong the spoils of the enemy.”

Senate courtesy, or “senatorial courtesy,” dates back to the nation’s founding. It’s one of those unwritten rules by which senators would support a colleague opposing a nomination from that senator’s state. It was a time when the Senate was more collegial, and members showed greater mutual respect. The idea was that a senator from New York would better know the qualifications and character of a nominee from that state than a senator from South Carolina.

The first noted case of a rejected nominee due to Senate courtesy was Benjamin Fishbourn, nominated by President George Washington to the post of naval officer for the port of Savannah, Georgia. Sen. James Gunn of Georgia spoke against the appointment, and the Senate deferred to Gunn, rejecting the nomination.

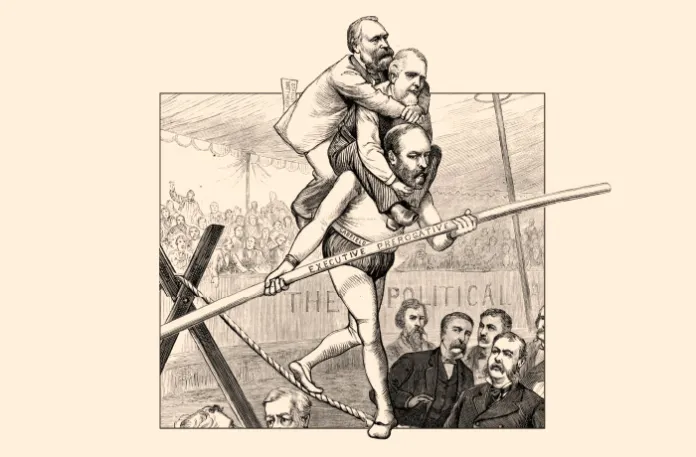

While it might have made sense at the time, it became a corrupting influence over the years, nearly allowing influential senators, including Roscoe Conkling of New York, to effectively control who presidents appointed to their administrations from their states, similar to ancient Rome and the practice of pollice verso during gladiatorial combat. Senators expected presidents to consult with them on appointments, essentially telling a president, “You’ll choose who I want in that role.”

It was Garfield who pushed back against the practice. He understood the constitutional process: the executive branch makes nominations, and the Senate can either accept or reject the nominee under its “advice and consent” powers. However, Garfield felt the process had turned on its head, almost to the point where the legislative branch was usurping the executive branch’s constitutional duties.

One might even call it “a threat to democracy.” After all, if influential senators from particular states get to call the shots for the administration’s appointments and nominations, how does it allow a president to shape his administration in a way that conforms to his vision for the country?

The Senate adopted the “blue slip” process in 1917. The blue slip is a form sent by a state to both senators after the president nominates someone to serve as a district judge or U.S. attorney in that state. It used to include appellate judges, but that practice ended in 2017. That process once served as a courtesy among senators. Still, more recently, it has been used as a partisan tool to prevent presidents of the opposing party from appointing ideologically aligned district judges in red or blue states.

It juxtaposes against what we see today, nearly 150 years later. An executive branch that most people believe has too much power, and a Congress that acts more like a Parliament, depending on who occupies the Oval Office.

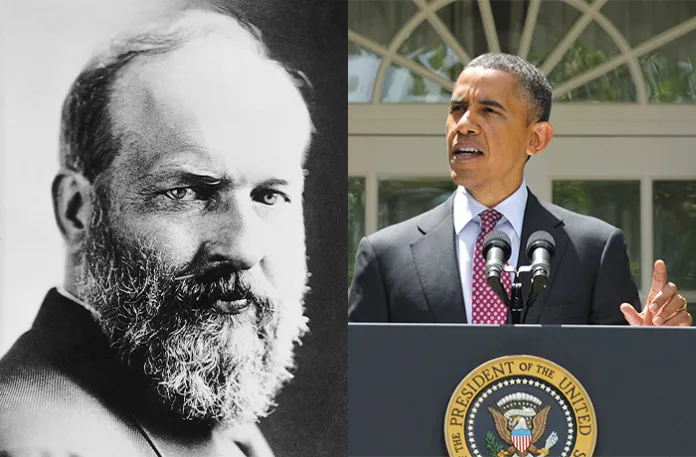

The New York Times recently published a story by Charlie Savage, titled “How Cheney’s Presidential Power Push Paved the Way for Trump to Go Further.” There is no ambiguity about Vice President Dick Cheney’s perspective on executive power. “When you’re asking about my view of the presidency, yes, I believe in a strong, robust executive authority,” Cheney said. However, the article doesn’t mention two people in drawing a straight line from Cheney to President Donald Trump: former Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden.

Obama ran on criticizing then-President George W. Bush for his use of executive power, promising to curtail it. Not only did he not do that, but he also expanded the use of executive power, going so far as to threaten action if Congress did not “act.”

Obama criticized Bush for warrantless wiretaps but later expanded their use. His administration tapped the phones of Associated Press reporters. The Obama administration labeled reporter James Rosen as an “unindicted co-conspirator” in an Espionage Act case, allowing the Justice Department easier access to his emails and phone records. Obama also claimed executive privilege in the “Operation Fast and Furious” scandal, which resulted in American guns and ammunition in the hands of Mexican drug cartels. Additionally, he authorized drone strikes in much greater numbers than Bush did — Bush approved 45-50 strikes, while Obama authorized around 350-500, including one that killed an American citizen.

Then there is the pièce de resistance of the Obama era: Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. Essentially, what it did was protect children born outside the United States from deportation if their parents had illegally immigrated to the U.S. For years, advocates pushed the president to implement the policy via executive action, and to his credit, he said he could not. For several years, he told people of the limitations. In 2010, he said, “I am not king. I can’t do these things just by myself.” In March 2011, he said, “With respect to the notion that I can just suspend deportations through executive order, that’s just not the case.” Two months later, he said he could not “just bypass Congress and change the [immigration] law myself. … That’s not how a democracy works.”

And then he did it anyway. He grew tired of Congress not passing immigration laws, such as the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, which would have codified DACA. The result was a policy immediately challenged in court and, 13 years later, remains unresolved. This was not a one-off for Obama either. As his second term went on, he made explicit threats that if Congress did not “act,” he would. In 2014, he famously said, “I’ve got a pen to take executive actions where Congress won’t, and I’ve got a telephone to rally folks around the country on this mission.”

Is it any wonder the country got a president who said, “I have an Article II which gives me the right to do whatever I want,” following the Obama era? The only difference between Obama and Trump on the exercise of executive power is that Trump doesn’t hide behind a pretense of doing something that is “necessary” because Congress won’t do it. He merely asserts he can.

It did not get any better when Biden won in 2020, despite promising to return to the “norms” that he claimed had been sorely lacking in the previous four years. Biden’s first foray into ignoring the separation of powers was when he pushed the pandemic-era rent moratorium despite a warning from the court that any further extension would have to come from Congress. He attempted to force private-sector companies to mandate COVID-19 vaccination for employees, using the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to enforce it. His most significant executive power grab was his attempt to appropriate $500 billion to relieve former college students of their student loan debt. When the Supreme Court struck it down, he tried another scheme, boasting on social media, “The Supreme Court blocked me, but they didn’t stop me.” That, too, was struck down by multiple district courts.

In the second term, of course, Trump has thrown away all pretense and essentially has adopted a unitary vision of the presidency. Congress is only there to do his bidding and nod approvingly at his executive actions, rather than challenge them. Naturally, Democrats have found their spine when it comes to executive overreach following 12 years of Democratic presidents, during which they, too, nodded along to the president without so much as a concern about overreach.

FILIBUSTER FOLLIES: BIPARTISAN THREATS TO THE SENATE’S WALL AGAINST CHAOS

Garfield proved nearly 150 years ago that the ship can be righted. No one in Congress should be so powerful as to dictate presidential appointments. As for the expansion of executive power, that too can be halted. Ironically, it will not come from Congress, which, during this time, will do or oppose whatever a president would like to do, depending on the party in power.

It will likely have to come from a sitting president who will say, “I am not going to do that via executive action. You people need to hash this out.” It will require a president who will have a more collegial relationship with opposing party leaders. It will require White House meetings that are not meant for television or sound bites. In other words, it will take actual work. As it stands, there is little chance it will happen in the next decade. But the true order of the constitutional system was restored thanks to Garfield. It can happen again more than 150 years later.

Jay Caruso is a writer living in West Virginia.