Fairies

A Dangerous History

by Richard Sugg

Reaktion, 279 pp., $25

The Dragon

Fear and Power

by Martin Arnold

Reaktion, 328 pp., $27

There is a sudden reversal at the ending of Yeats’s “The Stolen Child.” In the first three stanzas we hear the call of the world inhabited by fairies—the waters and the wild, Sleuth Wood in the lake, the hills above Glen-Car. It is into this untouched, enchanting world, a world beyond time and pain, that the fairies intend to steal the child. But the last stanza switches to a different, unmistakably human sweetness: man-made objects ranged round, the fruits of human labor stored up for a wintry future. The child stolen will be leaving all this behind, “For he comes, the human child / to the waters and the wild / with a faery, hand in hand / for the world’s more full of weeping than he can understand.” The coziness of the hearth—and the mortal capacity to understand tragedy—are absent from the ageless beauty of fairyland.

Yeats’s poem appears nowhere in Fairies: A Dangerous History, which is surprising for two reasons. First, because Richard Sugg’s book offers a richly detailed look at fairies in art and literature, emphasizing the Elizabethan period through our own. Second, because Yeats was a devotee of Celtic folklore, and while Sugg’s book is purportedly a general study of fairies, he is really interested in the legends and phenomena of the British Isles.

The first half of the book sketches the broad outlines of the fairy landscape through regional folklore and firsthand accounts. Among the fairies, there are the gentry, often tall and beautiful and given to hunting, fighting, and revelry. There are the smaller, more practically active types into which brownies and leprechauns fall. There are wood spirits and sea people and things which admit of no particular classification. There are the fairy islands that appear only once every century but from which the sounds of bells and singing float over the water. There are the changelings, supposedly sickly fairy children substituted for human, and so subject to brutal real-life abuses to make the fairies take them back. And there are the fairy doctors, the scammers who drew prestige and authority from claimed contact with fairyland and its healing powers.

Sugg leans heavily on the work of W.Y. Evans-Wentz, an Edwardian anthropologist given to raptures on the mystical qualities of ye olde Celtic peasant (possibly a hazard of the genre). Sugg also refers frequently to Robert Kirk’s The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies. Kirk, a 17th-century Scottish minister, is sometimes described as a folklorist, but the sense of analytical remove in the term is inaccurate: He was something closer to a travel writer of the underground.

One night in 1692, Kirk went out in his nightshirt for an evening stroll to the local fairy fort. He did not return alive. Nor is Kirk the only fairy amateur to meet a strange or untimely end after depicting the gentry in some way. The artist Richard Dadd painted the frenetic and arresting The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke in one insane asylum and then died in another asylum. Which direction the causality goes is for the reader to decide. But some accounts of fairy encounters include threats of reprisal upon publicity; fairies don’t like snitches any more than we do.

Sugg is always careful to differentiate firsthand narratives from widely accepted legends and to note the source and date and circumstances of a given account, but he emphasizes sources that treat their subjects with personal interest rather than as a tool of academic analysis. He is interested in everything the fairies might mean, but especially in what they are: powerful, inscrutable beings at home in a world of their own and capable of significant incursions into ours.

For instance, Sugg points out that it was common to delay, reshape, or relocate buildings in order to accommodate a reputed fairy easement. This practice has continued well into modern times in Iceland and some parts of Ireland and Great Britain. Fairies seem an alternative aristocracy, whose claims can supersede those of both landlords and real estate developers.

For Sugg, fairies represent the totality of an alternate society, one characterized by wonder, creativity, and harmony. In invoking a fairyland that is a dark mirror of our world, the fairy-tellers were, as Sugg has it, subverting our world’s social oppression, industrial rapaciousness, and Christian chauvinism. Sometimes this gets a bit hard to take, as when Sugg writes of Calypso’s island “Perhaps too, the feminine and masculine had not suffered the schism and the hierarchy which they would do under centuries of Christian misogyny.” But the corpus of myth to which Calypso belongs is an endless catalogue of rape.

Nor has fairy interest always tracked with progressive egalitarianism. In her 1999 book Strange and Secret Peoples, Carole G. Silver points out that Charles Darwin’s ideas combined with the psychical research modish in the late Victorian years to produce a kind of fairy phrenology. The little people became a racial category, with long genealogies of the putative pygmy races that once inhabited Britain and intricate accountings of whether “savage” races stood above or below elemental spirits in the astral order of being.

Sugg is correct that by all accounts fairies and Christian faith were at the best of times uneasy bedfellows. But he overstates the degree of subversion necessarily entailed by fairy beliefs. Like everything else involving them, accounts of the fairies’ cosmological place are multiple, contradictory, unpoliced, and uncertain. Some fairy beliefs are obviously heretical; others are merely highly speculative. One common narrative holds that fairies were neutral angels, who neither rebelled nor affirmed their allegiance to God, and were condemned to be a middle people, neither one thing nor the other, until the day of judgment.

As a fairy supposedly told one of Evans-Wentz’s sources: “We could cut off half the human race, but would not . . . for we are expecting salvation.”

Dragons are easier to get a handle on than fairies. Unlike fairies, dragons are defined by what they do: hoard treasure, breathe fire, eat maidens. They also possess a morphological consistency that for fairies only starts showing up when Victorian representations and Cicely Mary Barker’s illustrations became popular. A dragon may be closer to a snake or closer to a lizard, but is certainly some kind of reptile. And while dragons show up all over the world, they don’t represent an entire hidden people.

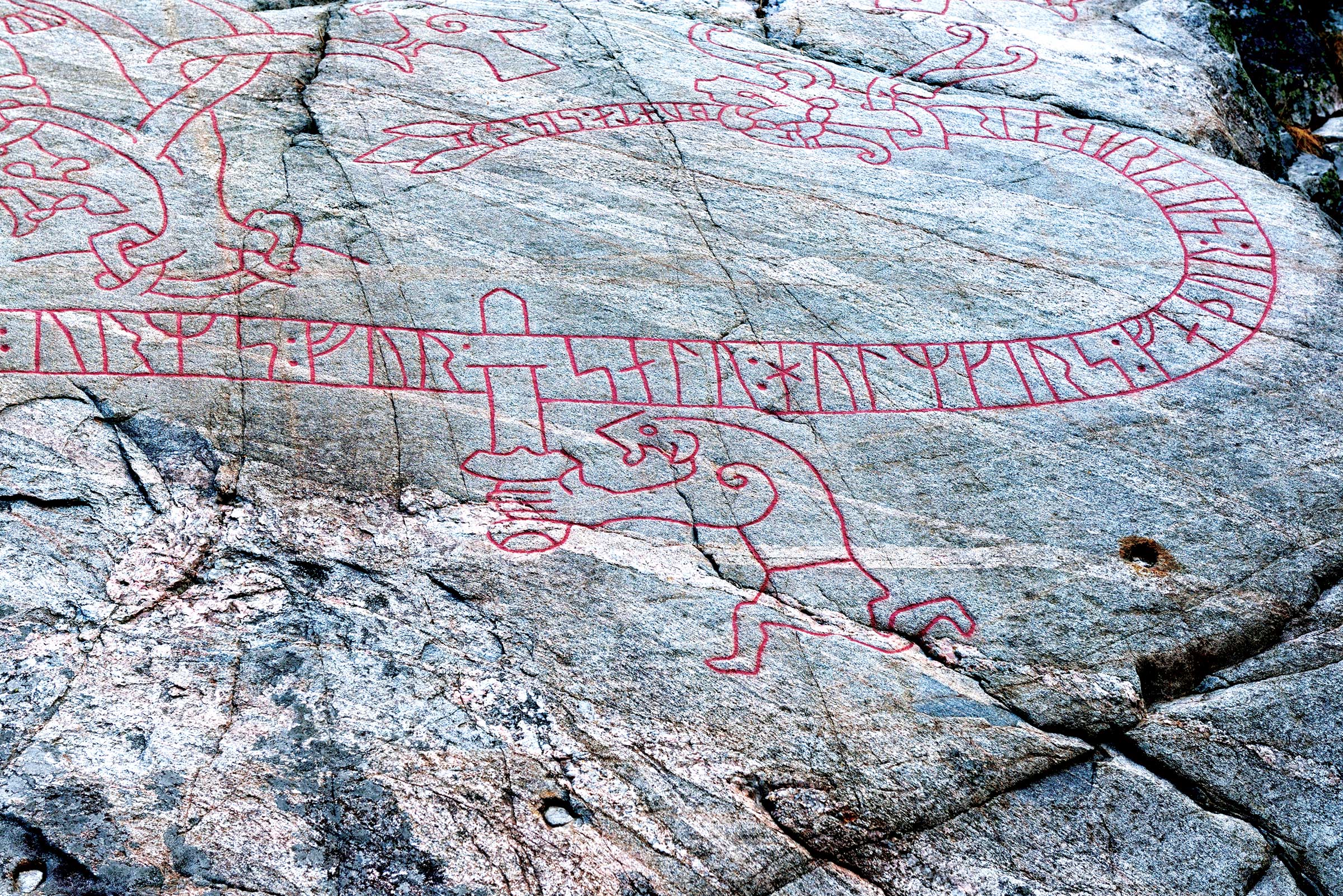

Martin Arnold’s The Dragon: Fear and Power explores the civilized dragon—the dragon as it has coalesced in an enduring and remarkably consistent body of legend, the dragon as it has cross-pollinated with other legends via the rise of powerful empires, and the dragon as it deals with the problems of civilization itself. In practice, this means that Arnold does not hew closely to any consistent vision of a dragon. Instead, he focuses on the best examples of dragons (or dragon-like function) within Semitic, Indo-European, and East Asian cultures, and finally in globally exported Western pop culture.

The maiden-capturing dragons of hagiography and medieval romance have largely faded away; it is the dragons of northern Europe, with their cunning and age and greed, that linger in the industrial and postindustrial imagination. And it is with these Norse dragons that Arnold really hits his stride. He moves from Nidhogg and the Midgard serpent to Beowulf, who ends his career facing a dragon, deserted by all but his faithful kinsman Wiglaf. The Beowulf cycle, Arnold contends, highlights the breakdown of reciprocal social obligations. The story deals with three great threats to peace: Grendel is social disharmony, or, as others have argued, bastardy; Grendel’s mother is the blood feud; and the dragon is greed.

Gold-lust and the usurpation of power also appear in the two other Norse dragon legends Arnold deals with at length. Both Fafnir and Gold-Thorir are men who kill and cheat for gold; guarding their hoards, both turn over time into dragons.

Unlike Sugg, who cautiously proposes that whether or not fairies are real, some of the extant testimony about them refers to something real, Arnold does not entertain the possibility. His study is of the dragon as it appears in art and literature, not alleged firsthand encounters with giant lizards—besides, there seem to be far fewer of these than fairy encounters.

Nevertheless, Arnold can’t resist a glancing inquiry into where dragons come from. He tentatively suggests that dragons represent the struggle between nature and culture, which is why he includes legends—like Hercules taming Cerberus—that don’t deal with dragons, strictly speaking, as much as other kinds of monsters. But his theory raises its own problems, as he concedes. First, a clean account of culture triumphing over threatening nature ignores the degree to which heroes like Hercules are agents of destructive chaos, brought down as often by their own vices as by their chthonic opponents. Second, a culture/nature opposition may account for monsters in general, but it can’t tell us much about dragons in particular—their seductive malice, their deadly authority.

Arnold also hints at an inverse theory. The dragon in its more potent forms may represent not the threats to culture-building but the terrifying powers implicated in a developing civilization. Dragon symbols appear in cartography, in alchemy, in military insignia. The impressive Chinese dragon often functions as a symbol of imperial authority and might. In a type of English folktale that Arnold calls “the anti-establishment dragon,” the dragon also symbolizes the excesses of elite power. So, for example, the Dragon of Wantley, a stand-in for a disliked landowning family, is described as dying thus: “First on one knee, then on back tumbled he / So groan’d, kickt, shat, and dy’d.”

It takes only a slight imaginative squint to see our contemporary world crawling with its own particular dragons, slithering and roaring through underground tunnels beneath centers of vast wealth, or soaring overhead and dropping fiery death on the embattled and oblivious alike.

In the end, Arnold falls back on Borgesian uncertainty: “We are ignorant of the meaning of the dragon in the same way that we are ignorant of the meaning of the universe.” This is not the most satisfying conclusion, but it is probably the most honest.

Fairies prove similarly difficult to pin down—unsurprisingly, as liminality is their defining feature. Contact with the fairies is dangerous not because they necessarily mean you harm but because you may become caught, betwixt and between, no longer safely fenced by the limits of human life. At best, fairy glamour is to be always listening for a music you once heard, longing for a food you once tasted, straining for the sight of a vanishing island. It is to be deaf to the cries of your own children, unable to stay yet unable wholly to leave them. It is, as David Thomson’s fisherman said of the selkie, for your sea longings to be land longings and your land longings to be sea longings.

Of course, there have been more optimistic accounts of the fairy effect on human life. When Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright posed for photographs with their paper cut-out fairies, Arthur Conan Doyle rejoiced:

Coming from the great popularizer of ratiocination, this may seem unbearably naïve. But the industrial-scale slaughter of the Great War was still fresh, including the the deaths of Doyle’s son and brother therein. The time seemed ripe for a breakthrough, and he was expecting salvation.