Only 10% of workers are now union members, according to the new Labor Department report on union membership, released in late January. And private sector unions, which peaked at 35% in 1954, now include just 6% of all workers as members.

The Biden administration has bent over backward to save private sector unions from their final destruction. It has bailed out their busted pensions, allocated stimulus grants to projects with rules skewed toward union labor, and even tried to strangle the gig economy with new regulations designed to force contractors back into traditional employee roles — all so that they can be unionized more easily.

HOUSE REPUBLICANS HOPE TO GET SOME TAX GOALS ENACTED DESPITE DIVIDED GOVERNMENT

But try as President Joe Biden has, it just hasn’t been enough. Automation (including not only factory machinery but also the gig economy), trade, high-profile union corruption cases, failing pension funds, and a string of adverse court rulings are among the many factors rendering private sector unions irrelevant to workers in most modern fields. This has led the unions to desperate measures, such as organizing esoteric, low-income professions, including graduate student teachers and video game testers.

Yet the story is quite different for unions in the public sector. The unionization rate of public employees remains robust, at more than 33% of all government workers nationwide. Local government workers are the most likely to be unionized, at a rate of nearly 39%, and public sector union members are concentrated in states that mandate collective bargaining. The states with higher rates of unionization seem to correlate with the nation’s least functional state governments: California (54.5%), Illinois (48.7%), New York (66.7%), and New Jersey (59.3%) among them.

As their private sector cousins starve, public employee unions are fat and happy — a strange development, given that there was no public sector collective bargaining at all 70 years ago, when unions were at their apex.

Public employee unions are as relevant and formidable as ever, thanks to the unique political power and influence they wield.

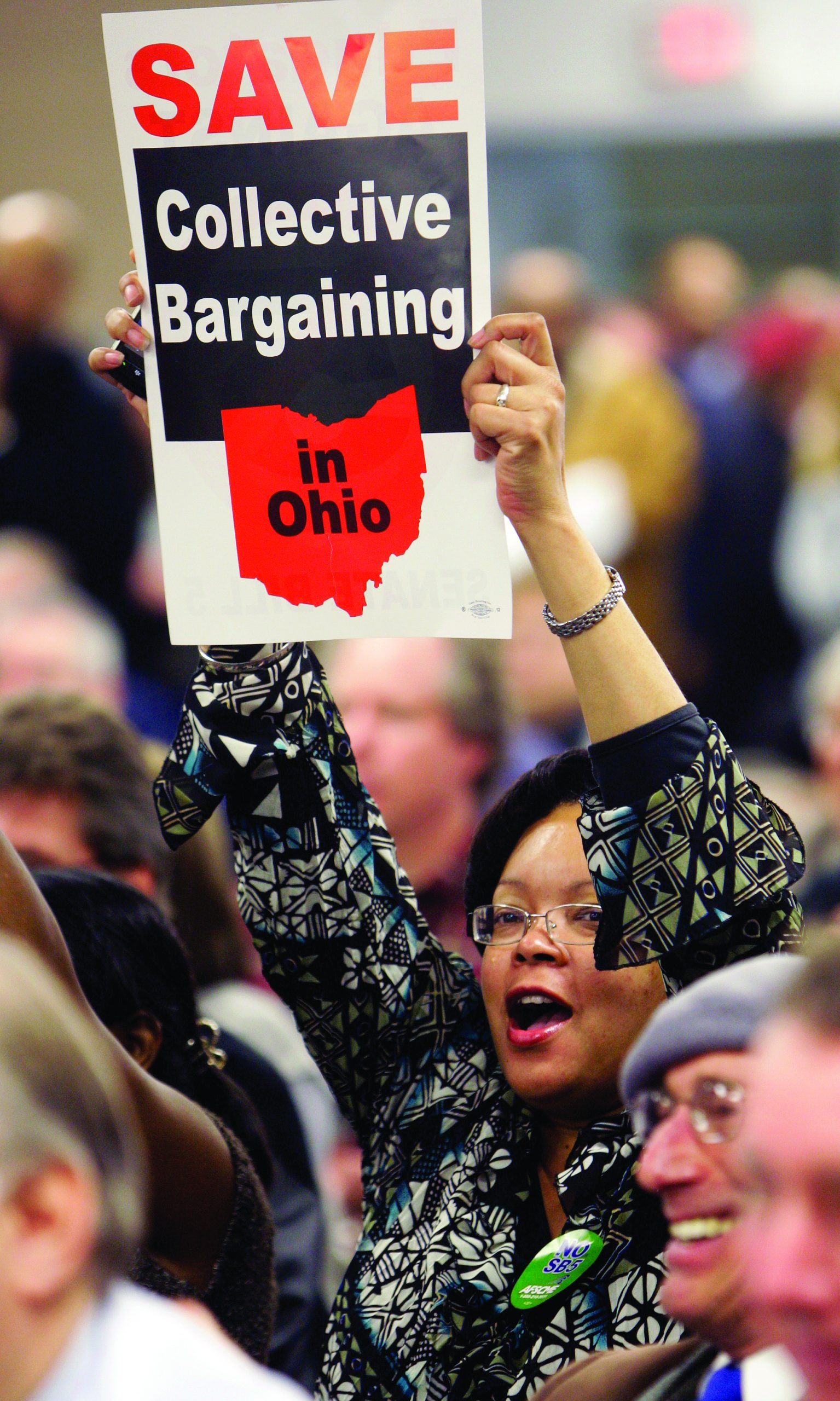

For starters, public employee union members can be relied upon, and are relied upon by Democrats in many states, to come out in force to support higher taxes and more government spending, to oppose anything that threatens their meal ticket. Sometimes, they protest such things peacefully. Sometimes not so much, as when they stormed the Capitol in Madison, Wisconsin, in 2011 to block the law that limited their collective bargaining power there. In Ohio, the unions actually did force a referendum to stop that state’s law limiting collective bargaining, and they won.

Even beyond their ability to project force through protests and voter mobilization efforts, public sector unions enjoy immense and undue influence over government decisions, often to the detriment of voters and taxpayers. To give one recent example, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, public sector unions literally dictated the Biden administration’s public health policies, as internal emails from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention later revealed. Teachers union bosses’ demands impressively superseded the advice of the scientific community when it came to closing public schools, or at least to providing an excuse, in the form of dubious federal guidance, for some states and localities to keep schools closed unnecessarily.

And health is not the only area where public sector unions get what they want. Biden’s American Rescue Plan of 2021 rained manna from the heavens upon state and local governments, especially in the area of education, to help keep these unions’ members on the payroll, whether or not they were still working. Biden also proposed rules that would essentially block most charter schools from receiving federal grants. This is something the teachers unions have been demanding, as nonunion charter schools are not only competing with their failing schools but showing them up all over the nation and cutting into the enrollment of traditional public schools.

Today’s stark imbalance of unionism between the private and public sectors would be puzzling to the politicians of the mid-20th century. None of them would have thought that, by 2023, unions would have become mostly a government thing. Indeed, to union bosses and union supporters in those days, the very idea of a public sector union seemed anathema to the spirit of both unionism and government. As AFL-CIO President George Meany put it, it is “impossible to bargain collectively with the government.” Or in President Franklin Roosevelt’s words, “The process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service.”

Unions, after all, had been created in order to help workers take home a fair share of the profits they were helping large companies generate in the industrial era. But government is not a company, and it makes no profit. To the extent that public employee unions control compensation and work conditions, then, they simply impose greater costs for taxpayers to bear.

“Unlike trade union negotiations, public employee unions have little downside risk with excessive collective bargaining demands,” wrote Philip Howard in his new book, Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions. “No matter how much unions take from taxpayers and the public good, government can’t go out of business.”

The collective bargaining process not only lacks constraints upon what unions can demand, but it also damages democracy itself. It effectively cuts elected officials out of the loop on critical policy questions. Instead of voters and their representatives making decisions about spending priorities through elections and then votes in the appropriate legislatures, the process we were all led to believe is the American system, those decisions end up being made in closed negotiating rooms, behind whose doors union representatives swap promises with friendly politicians or unelected arbitrators unilaterally settle issues between the unions and unfriendly politicians.

In many cases, no one is there to represent the interests of taxpayers, nor even of those whose public services might be cut off so that the union can secure higher pay or better benefits for government employees.

John F. Kennedy was the first president to approve collective bargaining in the federal workforce. In 1962, he issued an executive order titled “Employee-Management Cooperation in the Federal Sector.” The order described this as promoting “the efficient administration of the government” and the “effective conduct of public business.”

In his foreword to Not Accountable, former Gov. Mitch Daniels (R-IN) derides Kennedy’s words as “the most ironic, and most historically demolished … ever written in a presidential executive order.” Daniels demonstrates his point with an example from his own career. Immediately upon taking office in 2005 in the Hoosier State, he struck down Indiana’s collective bargaining agreement with state workers, something that, by a quirk of history, he had the power to do unilaterally, unlike governors in most other states.

Daniels struggled with this decision beforehand, but in the end, he found the choice easy. His reasoning had less to do with the added expense of union collective bargaining and more to do with the inflexible work rules that the unions had forced upon his state.

“Ultimately,” he wrote, ”I concluded that the myriad changes we hoped to bring to a broke and broken state government could not be achieved if every step could become the subject of a rules-laden negotiation under a 170-page collective bargaining agreement.” Daniels called this the most consequential decision he ever made, with uncontroversially beneficial results for Hoosiers. He wrote:

“After eight years with the freedom to recruit and place top talent in key jobs, separate some agencies for priority attention while consolidating or abolishing others, and reward employees for their performance rather than their seniority, government became not just solvent but effective. Tax refunds were received in two weeks or less, citizens were in and out of a motor vehicle license branch in 12 minutes or less, and a national survey found 77% confidence in the job Indiana state government was doing.”

Wisconsin’s more famous and bitterly contested Act 10 produced similarly salutary results for the Badger State. The measure, which made Gov. Scott Walker (R-WI) a household name, eliminated wages and benefits altogether from the realm of collective bargaining for state and local government employees. This freed up governments at all levels to make their employees start paying a fair share into their own health and retirement plans, as all other workers do.

The state’s public employee unions were devastated. Act 10 ended the automatic deduction of union dues, and they have lost 56% of their members since 2011. Meanwhile, according to state data and projections by the MacIver Institute through 2022, Act 10 has since saved the state government, the state university system, and Wisconsin’s cities, counties, and school districts a combined $15.3 billion. With all that money freed up for other priorities, Act 10 is now so popular that no one in Madison from either party dares propose its repeal.

Another example was the wholesale replacement of New Orleans’s abysmal public schools with nonunion, independent charter schools after Hurricane Katrina. “It was as if someone switched on the light,” wrote Howard, an attorney whose writings on bureaucracy and the law are voluminous. “High school graduation rates improved from 52 to 72 percent, and gaps between racial groups narrowed.”

Such negative examples abound of public sector unionism’s ill effects. And then there are the positive examples of how unionism makes state and local governments unmanageable.

“California, with 300,000 teachers, is able to terminate two or three per year for poor performance,” Howard wrote. To read these words is to understand the problem immediately.

In Baltimore, Fox45 News recently reported that 23 city public schools have exactly zero students proficient in math based on the latest state test scores. To make matters worse, there are 20 additional schools with only one or two students proficient in math. This school district spends roughly $21,000 per student. In any real-world enterprise, this would be treated as an emergency. Everyone involved in running these schools would be fired immediately and replaced. But in the world of collective bargaining, this is impossible, so Baltimore schools will just continue to fail forever.

With such examples as these, Howard argues persuasively that “the abuse of public power by public employee unions is the main story of public failure in America. … It is not possible to bring purpose and hope back to political discourse until, as a threshold condition, elected leaders regain the authority to run public operations.”

This is the very problem Howard tries to attack next, as the title of his book suggests. Not only are public employee unions a nuisance to the taxpayer and a drag on government effectiveness, but they also comprise an unconstitutional fourth branch of government. “Government cannot delegate to private parties essential governing choices,” Howard said. Yet that’s exactly what happens when negotiators or arbitrators make policy disguised within collective bargaining agreements.

The very first example he provides in his book is that of Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer now in prison for killing George Floyd. Chauvin likely would have been removed from his job long before his fateful confrontation with Floyd if not for a public employee union protecting him against multiple civilian complaints.

“Under the police union’s collective bargaining agreement,” Howard wrote, “the police commissioner lacked the authority to dismiss Derek Chauvin, or even to reassign him.” In fact, only 12 out of 2,600 police complaints in Minneapolis over the previous 10 years had resulted in disciplinary action. That’s collective bargaining at work.

For Howard, this raises the deeper constitutional question of who is really in charge. Should a crucial policy governing police conduct be made by elected and therefore accountable officials and their appointees? Or should it be made behind the scenes in negotiations with unelected union bosses not accountable to the sovereign people?

This isn’t just true of police unions, either. It is true of teachers unions and federal workers’ unions, as well.

“More federal employees die on the job than are terminated for poor performance,” Howard said. He isn’t kidding. I remember being in Washington many years ago when I first read the story about an employee with the Environmental Protection Agency (actually, one of several) who watched pornography on his work computer almost all day at work. I lost track of the story because it wasn’t resolved until just before the 2016 election, but incredibly, this man was not fired from his $120,000-per-year job. He was allowed to make a deal to retire after two additional years on the payroll.

And of course, mere neglect of duty is not the worst offense that can’t get you fired. During and after the 2014 scandal at the Department of Veterans Affairs, the American Federation of Government Employees went to the mat for those very malingering employees who had been gaming the VA’s computer scheduling system to deprive veterans of timely doctors’ appointments without losing their bonuses. Consequences for our actions? Sorry, that’s against the collective bargaining agreement.

At heart, such union contract provisions represent policy. Consider this anecdote from the early days of public employee unions:

This is why Howard believes it is obvious that public sector unions form an illegal locus of power that has placed itself outside the reach of the elected legislatures and executives. As long as “no decision is too small to be vetoed by a union entitlement,” unions are effectively frustrating the institutions of democracy itself. This in turn is making citizens “justifiably cynical and distrustful because modern government is organized to fail.”

But if collective bargaining agreements are putting the unions outside the reach of democratic accountability, how can this problem be fixed democratically? Howard believes the Constitution and Supreme Court jurisprudence provide a means to untangle the mess into which the public employee unions have made of governing.

And the Supreme Court’s decision in Janus v. AFSCME, Howard explained, was “a major turning point” because Janus embraced the idea that the very act of collective bargaining by a public employee union is inherently political. “Most of Janus,” he said, “is about how public unions have rendered government inoperable.”

But even if collective bargaining agreements in governments across the country contain unconstitutional delegations of government power to private parties, how does a case like that get litigated? The Supreme Court, for example, has never been willing to enforce one of the provisions upon which Howard relies most heavily: the Article 4 guarantee clause of the Constitution, which states that “the United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government.”

Can a state liberate itself from the anti-republican death grip of collective bargaining agreements? Howard said he believes it can happen if governors bring cases challenging union controls over their state constitutional powers.

“The claim would be to invalidate the statutory obligation to bargain because it disempowers the elected executive,” he said. For example, how is it possible for Illinois to have a law that says collective bargaining agreements supersede any statute? Some court has to step up and invalidate such provisions, or else Illinois no longer has a republican form of government.

FOR MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER MAGAZINE

Howard also believes that a president who simply refuses to honor such unconstitutional controls could deliberately invite a lawsuit over the very same issues in the federal government and go all the way to the Supreme Court.

It is a matter of speculation how the high court would react to such a case. But it is an exciting thought. If only more elected leaders could be given access to Alexander’s sword, as Daniels once was, to unfasten the Gordian knot that has American government hopelessly and helplessly tied up. Who knows? Governments all over America might just suddenly … start working.

David Freddoso, the New York Times bestselling author of The Case Against Barack Obama, is the Washington Examiner’s online opinion editor.