Read a comparison between Presidents Donald Trump and Richard Nixon, and more often than not, it begins and ends with scandal, abuse of power, and corruption.

The term “Watergate” is synonymous with all of that, and people often use it to draw a direct line between Nixon-era abuses of power and those of today. But those parallels obscure a more consequential comparison for conservatives, but not necessarily the Republican Party: The connection between Trump and Nixon is not in temperament or misconduct, but in how each understood the role of government in shaping economic outcomes.

This comparison is instructive precisely because it cuts against modern assumptions about Republican economic policy.

Richard Nixon governed a Republican Party that looked very different from the one Americans associate with conservatism today. Economic debates inside the GOP had not yet hardened into doctrine, and the postwar consensus that the government had a legitimate role in managing economic stability remained largely intact. Skepticism of federal power existed, but primarily among activists and grassroots organizations, as well as publications such as National Review. However, it had not yet become a fundamental principle for the GOP.

That context matters because it explains how Nixon governed while in office. By the early 1970s, the United States was facing rising inflation, slower growth, and mounting pressure on the postwar Bretton Woods monetary system, also known as the “gold standard.” Nixon viewed those pressures not as problems that would eventually work themselves out through market forces, but as political and economic threats that required direct government action.

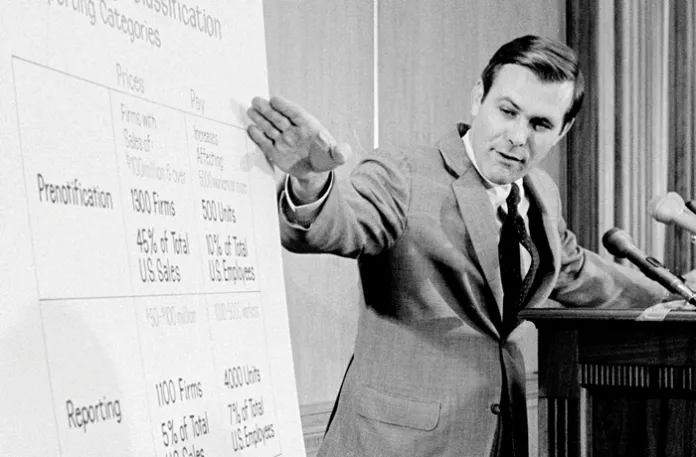

In 1971, he enacted a nationwide 90-day wage and price freeze, followed by a system of ongoing controls administered by federal boards. This was not a small intervention. It was the federal government directly setting wages and prices across the economy, something that would later become politically untenable within the Republican Party. The policy was intended to thwart inflation and stabilize the economy, but it also marked one of the most direct assertions of federal control over prices and wages in modern American history.

Nixon’s trade policy followed a similar logic. That same year, he imposed a temporary import surcharge, or tariff, as part of a broader effort to protect domestic industries and address balance-of-payments pressures tied to the unraveling of the Bretton Woods system. The policy’s structure differed from later tariff implementations in that it was temporary, but the approach remained the same. Market outcomes were not treated as hands-off — they were subject to government action when economic or political conditions demanded it.

Nixon’s comfort with using government for economic purposes extended beyond prices and trade. Rather than dismantling the New Deal or the Great Society, he consolidated and expanded parts of it. He signed legislation creating Supplemental Security Income in 1972, expanded food stamp eligibility, and advanced a guaranteed income proposal through the House twice via the Family Assistance Plan. Although the proposal ultimately failed in the Senate, the effort itself put Nixon outside the tenets of free market capitalism and market dynamics.

Nixon’s presidency reflected a managerial view of the economy. He didn’t reject capitalism but felt it needed to be actively overseen and, in some ways, controlled.

It took less than a decade for that approach to be eclipsed.

In 1964, Ronald Reagan delivered his “A Time for Choosing” speech on behalf of Barry Goldwater during the latter’s presidential campaign. The address marked a significant break with the postwar consensus that had shaped Democratic and Republican economic policy for decades. Reagan framed government intervention not simply as inefficient, but as fundamentally corrosive.

Reagan said, “This is the issue of this election: whether we believe in our capacity for self-government or whether we abandon the American revolution and confess that a little intellectual elite in a far-distant capital can plan our lives for us better than we can plan them ourselves.” For Reagan, markets were presented not just as engines of growth, but as part of the guarantee of individual liberty because “a government can’t control the economy without controlling people.”

Reagan carried that framework into the California governor’s office and later the presidency. While divided government required compromise, Reagan’s approach to compromise was tactical rather than ideological. His often-cited 80-20 rule captured that distinction. If he could get most of what he wanted, he accepted partial victories with the expectation that policy would continue moving in the same direction. Give-and-take was necessary, and he understood the process.

Reagan was willing to negotiate over implementation, timing, and legislative detail. He was unwilling to legitimize the idea that government intervention in markets was desirable in itself, and he often spoke against it in speeches and writings. Even when he worked with Democrats on tax reform or Social Security, those compromises allowed him to reinforce his economic worldview.

Reagan’s view of government and free-market capitalism would reshape the Republican Party for decades to come. His presidency obliterated the model Nixon used just years before, making the case that government should shrink, get out of the way, and allow markets and people to do the work.

This was the economic framework Trump inherited and busted through like a bull in a China shop. Trump’s approach to economic policy has many similarities to Nixon’s, with the added bonus of public bluster and bravado that would have made “Tricky Dick” blink.

The easiest to understand is tariffs, not only because they have become central to Trump’s presidency, but because they reflect one of the few, if only, positions he has held consistently for decades. Long before entering politics, when he was building casinos in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in the 1980s, Trump publicly argued that foreign countries, particularly Japan, were “ripping off” the U.S. through trade. So it was a position ingrained in his mind long before he considered running for president.

That history matters because it distinguishes tariffs from Trump’s other policy positions, where he is likely to pivot at any given moment. Trump has long viewed trade deficits as evidence of weakness and tariffs as a corrective tool. While president, he’s treated them not as a temporary bargaining chip, but as a long-lasting policy instrument and a bludgeon meant to punish countries that cross him.

Trump repeatedly asserts that tariffs are paid by foreign countries, even though they are not. It is part of why he uses them as a punitive measure — he operates under the false assumption that countries are writing checks to the U.S. Treasury. The reality is that domestic importers bear those costs and pass them through supply chains, ultimately causing consumers to pay higher prices. In functional terms, tariffs operate as a tax.

Trump’s love affair with tariffs differs from Nixon’s in scope and permanence, but the logic is comparable. Market outcomes are not neutral or self-correcting. Trade is not to be left to institutional norms or economic theory. It is something the state could and should manage directly when outcomes are viewed as politically or economically unacceptable.

The consequences were predictable. Trump’s trade war with China imposed high costs on American farmers, particularly in export-dependent regions that formed the backbone of his political coalition. Rather than retreat from the policy, Trump responded with tens of billions of dollars in direct federal payments to offset those losses. In short, it was a form of corporate welfare justified as compensation for the economic effects of federal trade policy.

Trump’s willingness to intervene extends beyond trade. He repeatedly and publicly pressures the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates, challenging long-standing norms around central bank independence. Presidents have historically sought favorable monetary conditions, but Trump does so openly, framing interest rate policy as responsive to his whims rather than as insulated from them.

He also advanced proposals designed around helping the working class that would have been politically improbable within the Republican Party only a decade earlier. These include a recent proposal to cap interest rates on credit cards, extend mortgage terms to 50 years to address housing affordability, and plans to ban institutional investors from purchasing single-family homes. He’s also taken to having the federal government hold equity stakes in private companies.

The reaction from the Republican Party has ranged from quiet disagreement in some quarters to silence to open acceptance. Traditional conservatives and free-market advocates have been horrified, while populist voters cheer on the moves.

On several of these issues, figures on the Left, including Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), found themselves aligned with Trump. Sanders’s support for aggressive state intervention has been ideologically consistent. Trump’s comfort with similar tools highlighted how far Republican economic assumptions have shifted.

Trump did not introduce this governing instinct to American politics. He revived one that had largely fallen out of favor within the GOP. Like Nixon, he treats government power as a legitimate means of achieving economic and political ends. Unlike Reagan, he does not frame intervention as a necessary evil to be minimized through compromise.

Seen this way, the Trump–Nixon comparison becomes less about scandal and more about economic governance. Both presidents operated on the assumption that markets exist to serve national and political goals, and that government has a role in shaping outcomes when markets fail to do so.

This is why the constant return to Watergate analogies ultimately obscures more than it clarifies. Corruption is easy to condemn and process. Economic governance is more difficult because it forces the Republican Party to reconsider principles that it has spent decades treating as settled.

Nixon’s downfall did not lead to a wholesale rejection of his economic policies — Reagan’s rise did. What Reagan accomplished was not simply a policy shift, but a reframing of markets and state power that endured long after tax cuts and the end of the Cold War. Trump governs outside of that framework.

Seen through that lens, Trump is less an aberration than a stress test. He exposes how contingent the party’s commitment to Reaganite economics has become once stripped of rhetoric. When intervention produces political and electoral wins — Trump won Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin twice, while George W. Bush could not — resistance fades.

This tension will outlast Trump himself. The question is, how far will it go within the entire GOP ecosphere?

Most of it all centers on Trump, and while some believe that once he’s finally gone, the GOP will slowly find its way back to a more free-market outlook on economic issues. That said, with a populist Republican voting bloc making a lot of noise, the question becomes whether the party can shift in another direction.

That makes the Trump-Nixon comparison useful not as a warning about scandal, but as a guide to where the party may be headed. Right now, it is mostly about the person, but it should be about competing visions of what government is for and what its role is.

On that question, the Republican Party has yet to provide a clear answer.

Jay Caruso (@JayCaruso) is a writer living in West Virginia.