Halfway through Julian Barnes’s latest book, a woman named Jean explains to the author that not all his books have worked for her. “This hybrid stuff you do — I think it’s a mistake,” she says. “You should do one thing or the other.” Keen to defend himself and his methods, Barnes retorts: “I don’t mind you not liking my books, but you are mistaken if you think I don’t know exactly what I’m up to when I write them.”

For over four decades, Barnes has been up to all sorts of literary shenanigans. Some of his books have been conventional, recognizable fiction or nonfiction; others have broken the rules by blending or subverting genres. Levels of Life (2013), written after the death of Barnes’s wife, starts out as a history of ballooning and then shapeshifts into a meditation on grief. Flaubert’s Parrot (1984), Barnes’s homage to his favorite French writer, is a riotous display of postmodern pyrotechnics which dispenses with fluid narrative, experiments with form, and mashes up fiction, biography, and literary criticism.

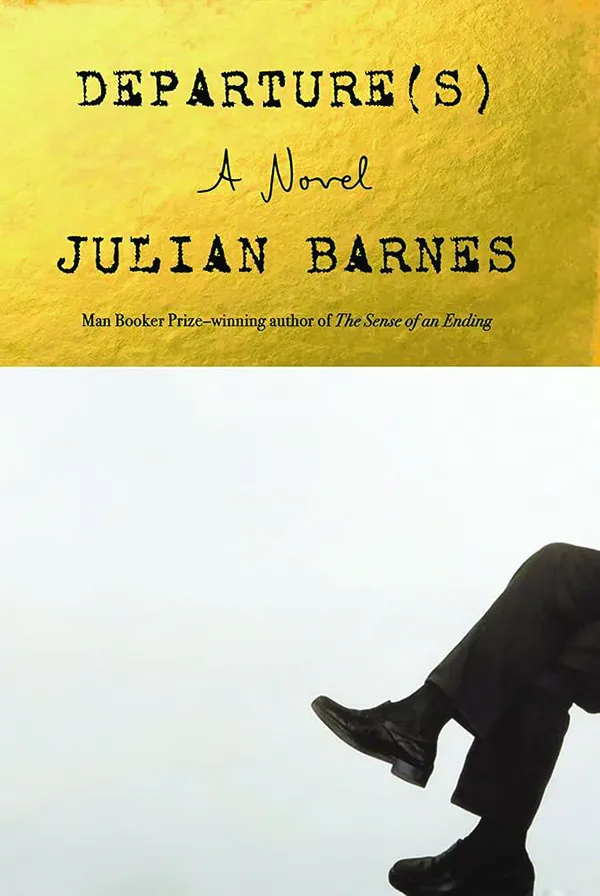

Barnes’s new book is another example of his “hybrid stuff.” Departure(s) is categorized as a novel and, therefore, fiction. However, it also resembles a memoir, and so “autofiction” seems a more accurate designation. There are two additional introductory points worth mentioning. One is that the book appears on the occasion of Barnes’s 80th birthday. The other is this declaration, which Barnes, as narrator, delivers at the beginning as part of a mission statement: “This will be my last book.”

No one can accuse Barnes of shirking his literary duty and hanging up his pen too early, especially when they read here about the health scares and crises that have plagued him in recent years. If Departure(s) really is the Booker Prize winner’s swansong, then it comes at a suitable juncture, before powers wane and creativity dries up. This is an author quitting while he is ahead, and leaving us with a fitting reminder of how he can be, by turns, playful and poignant.

At the heart of the book is a tale involving two on-off lovers. It is presented in two parts, “as it was lived in two parts.” Barnes assures us it is a true story, albeit one that comes with several “caveats”: he has changed the names of the protagonists, and he only tells — because he only knows — the beginning and the end of the story. In a section devoted to that beginning, he takes us back to his days as a student at Oxford in the 1960s. It was there and then that he brought together two separate college friends of his, Stephen and Jean. Stephen is soft-spoken and very tall; “when he threw his arms about he appeared to be heading off in different directions at the same time.” Jean is alluring and outgoing: “She headed straight towards things, and ideas, and people; she took them on, rather than being taken on herself.”

Their relationship unfolds, and their love grows. Barnes goes from matchmaker to third wheel. Besides hanging out with the couple, he acts as a sounding board to each of them, particularly when they individually voice their shared predicament: “I’m afraid it’s reached the point where we either marry or split.” In the end, they split, and after university, all three of them go their separate ways.

So ends a short chapter and a somewhat threadbare story. But its second part, which comprises the bulk of a later, much longer chapter, proves more substantial. One day, 40 years on from Oxford, Barnes, now an established writer, receives a letter from Stephen out of the blue. When they meet up, Stephen asks Barnes to help him reconnect with Jean. The erstwhile lovers become “rekindlers” and their “second go-round” results in a wedding, with Barnes appointed best man. In time, he assumes, once again, another role, that of confidant. As husband and wife experience a special strain of marital strife (“what might we call it?” Barnes wonders. “Reattachment Dilemma? Here-We-Go-Again Syndrome?”). The author, refusing to take sides, listens to their anxieties and gripes and tries to offer solutions. Stephen finds it hard to read Jean; Jean believes Stephen is over-attentive. “I just wish he wouldn’t be in love with me all the time,” she tells Barnes.

How the relationship pans out is for the reader to discover. But while it is at the center of Departure(s), it is not the book’s only subject matter. Barnes calls it “a story within the story,” and weaves around it if not other stories then a series of musings on diverse topics, along with accounts of his medical ordeals.

The episodes devoted to Barnes’s ailing health and hospital visits feel far from the realm of fiction. He reveals that in 2020, just prior to lockdown, he was diagnosed with a rare kind of blood cancer. Expecting to be issued a death sentence, he learns instead that it is incurable yet manageable (“that sounds like…life, doesn’t it?” he remarks). Barnes’s diary excerpts chronicle grueling treatment, but here and there he sprinkles in black humor or finds silver linings: “At seventy-five I am much better off than the young, who are having a year or more of their lives stolen.” In a later section, Barnes takes stock of his situation. He has inherited Jean’s old Jack Russell, Jimmy, who at 112 in human years is “well ahead of me in decrepitude.” Barnes sometimes falls and forgets things, but in the main, he functions: “The head and the heart are still working, as the body declines. But better that way round,” he says. He is resigned to his fate and content with his lot. What he is not comfortable about is breaking a promise to his former friends.

Authors nearing the end of their careers, and indeed their lives, commonly turn their attention in their final books to the two M’s — memory and mortality. Barnes is no exception, although to give him his due, he has engaged with these themes throughout his work. But Departure(s) is as much about morality as mortality, for Barnes also explores an ethical conundrum. At Jean’s behest, he swore on a Bible that he would never write about her or Stephen. He betrayed their trust and was, in his words, “parasitical upon their lives.” Barnes comes clean, and in doing so, he highlights a flaw in his storytelling. “I follow you: if I broke that oath, how dependable is my promise to you of authenticity?” We question Barnes’s reliability as an author in a different way when he informs us that his remembrance of the couple at university “amounts to a chaplet of moments and images, worn away like rosary beads.” Are we getting an accurate version of events? Does it even matter?

THE HUNT FOR THE KILLERS OF EINSTEIN’S FAMILY

Barnes’s book, though slender, is packed with delights. His analytical passages on remembering and forgetting contain insightful close readings and case studies, and bring in a range of figures from Marcel Proust to Jimmy Carter. Barnes writes with candor about his aches, pains, and fears, and reflects on fallen friends such as Martin Amis and Christopher Hitchens. Gloomy ruminations on death and dying are enlivened by dry self-deprecation or takedowns from short-tempered, sharp-tongued Jean: “Love, in reality, Mr. Novelist, isn’t how you and your breed depict it.”

Barnes may show some signs of running out of steam (“And so on” peppers the narrative), but not of ideas. With his last offering — “my official departure” – he goes out on a high note.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.