Tackle America’s retirement problem, or risk the rise of the Islamic State.

That stark choice is the direst consequence of Washington’s fiscal mess, sketched by Bruce Josten, top lobbyist at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

For several years, Josten has pressed the case that the federal debt, and in particular the tab for retirement programs, is an urgent concern for business, even if executives don’t see its effects firsthand the way they do for more traditional business worries such as taxes or regulations.

As it becomes ever clearer that taxation cannot pay retirement benefits that have been promised, the Chamber has made entitlement reform and debt reduction an urgent priority of its lobbying.

PART 2: Comrades in arms

Social Security checks and prescription drug bills for seniors will drain money away from road building and other infrastructure, scientific research and basic administration that every business needs in order to be profitable.

It’s happening already, Josten says during an interview in his office at the Chamber’s imposing headquarters across H Street from the White House.

It’s not just businesses that are being affected, he says. It’s also the safety of citizens, as the Pentagon has to compete for it’s scoop from a shrinking pot of revenues left over after the Social Security Administration and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services take their growing share.

“Part of your economic might is a byproduct of your military might and, by the way, your military might is a direct result of your economic might, OK? So these things are all relatable,” Josten says.

PART 3: Business on 2016 frontline

The rhetoric matches the scale of the political challenge facing the Chamber.

To represent business, the Chamber must advocate lower spending and debt reduction. At the same time, it wants some government programs that benefit businesses to be maintained, an attitude that is not shared by many conservatives in the Republican Party.

As a result, the Chamber must press for reform of entitlement programs that are fiercely defended by liberals, while simultaneously avoiding overly broad spending cuts that increase fiscal pressure on infrastructure and research programs that business holds dear.

This position will be put to the test this year in a congressional showdown over spending caps on non-entitlement spending of the kind the Chamber wants to continue. Every Republican candidate will have to deal with questions on this issue during the 2016 campaign.

Squeezing out

No business owner or manager may care about how much debt the Treasury is issuing.

The federal debt, currently stuck beneath a ceiling of just over $18.1 trillion, is a collective national problem, not one that individuals may notice day to day. As a business owner goes about his or her routine of buying and selling, the federal debt is unlikely to seem as pressing as, for example, the possibility of a new tax or more intrusive paperwork.

Yet the indirect effects of the national debt are apparent and causing trouble in unexpected places, such as at the Canadian border between the cities of Detroit and Windsor, Ontario.

There, Michigan is trying to build a second bridge between the two countries to accommodate the heavy trade that currently must cross one 85-year-old span. Some 8,000 trucks cross that bridge each day and then go through 17 stoplights before getting to Canada’s Highway 401 seven miles away.

Canada and the U.S. agreed in 2012 to build a new $4 billion bridge, and businesses on both sides cheered. But across-the-board spending cuts in 2014 obliged American officials to tell Michigan’s governor that $250 million that had been promised for a customs plaza was suddenly not available.

Three months ago, Ottawa bailed out Washington and ponied up the money.

“When the government of the United States can’t come up with $300 million to build a customs plaza,” says Rich Studley, CEO of the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, “that really drives home how bad the situation is.

“And frankly, it’s an embarrassment that we’ve had to go begging to our Canadian neighbors.”

The bridge is just one example of many that, for Studley, bear the imprint of federal fiscal irresponsibility.

He cites growing concern among state Chamber members that the feds won’t be able to help control invasive species in the Great Lakes, which threaten water quality and could harm tourism. Separately, businesses are concerned about the upkeep of roads in the state, even as their upkeep is threatened by the exhaustion of the federal highway trust fund at the end of May.

Studley accepts Josten’s logic that businesses are threatened by relentlessly growing government spending on entitlements, and that even national defense is being squeezed out of the budget. The Michigan Chamber will continue to spend 80-90 percent of its money on local state issues, he says, but it will use the 2016 election to press candidates for detailed plans to reform entitlements.

Record low spending

It’s sometimes difficult to realize that, setting aside entitlement spending, which happens automatically without congressional action, federal government spending is near historic lows as a share of the economy.

President Obama and Democratic majorities in Congress spent heavily during his early years in office, even as the recession took a scythe to tax revenues. The yawning gap between revenues and spending generated annual deficits of more than $1 trillion. Since the start of the recession in December 2007, federal debt held by the public has doubled to 74 percent of gross domestic product.

But the rise of the Tea Party in response to ballooning deficits began to stanch the flow of spending when Republicans took over the House in 2011 and challenged Obama to a series of fiscal showdowns.

Bitter negotiations have cut the deficit year after year. But the savings have come predominantly from discretionary spending, not entitlements.

Discretionary spending is everything people think of when they picture government. Half of it is defense spending and half is everything else, notably infrastructure, job training, scientific research, education, welfare and law enforcement.

Setting aside Pentagon funding, which is at a historical low, discretionary spending is at its lowest since consistent records began in the 1960s, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-of-center Washington think tank.

Non-defense discretionary spending is projected to shrink further, from 3.3. percent of gross domestic product in fiscal 2015 to 2.5 percent in 2025, the Congressional Budget Office says.

The CBO, which provides analyses for members of Congress, says the government will pay out more for debt interest by 2022 than it does on all non-defense discretionary spending.

Rising retirement

The proximate reason that discretionary spending has been constrained is that the 2011 Budget Control Act, hammered out in a bruising fight between Obama and Republicans, called for tough automatic cuts if the two sides did not reach a better agreement that included entitlement reforms or tax increases. They didn’t.

But something else happened in 2011 that better explains the current fiscal fiasco. In that year, the first baby boomers turned 65 and began to retire.

The demographic bulge caused by the birth of 80 million people (including immigrants) between the end of the Second World War and mid-1964 explains the mismatch between expected revenues and projected spending.

Currently, there are 49 million retirees collecting Social Security checks, according to the trustees’ report. When the last baby boomer reaches retirement age in 2029, there will be 71 million, even assuming that one-fifth of boomers will by then be dead.

Far more retirees will be supported by far fewer taxpayers — the reverse of the situation that prevailed when federal retirement programs were created.

In 1945, there were more than eight working-age Americans for every person of retirement age. There were fewer than five by 2010, on the eve of Baby Boomer retirement. There will be fewer than three by the time Boomers stop retiring.

Demographics mean Social Security and Medicare costs will grow faster than economic output through 2030, according to the program’s trustees, setting aside growth in health care expenses.

Altogether, Medicare and Social Security have $41.8 trillion in unfunded liabilities over 75 years, the trustees estimate.

“You’re going to have to rearrange the entire funding structure here, because demographics determine reality,” Josten says.

Josten, a thin 64-year-old with a faint beard and swept-back silver hair, easily recites dollar figures and statistics on entitlements and demographics. He races through a litany of facts to emphasize the mess America is in, pausing every few minutes to ask, “See what I’m saying?”

He supports a raft of solutions, including raising the retirement age from 67 to 70 and changing the measurement of inflation to allow benefits to grow more slowly, as well as means-testing for richer beneficiaries. He even supports raising taxes.

He also has kind words for the Medicare overhaul proposal championed by Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., “kind of the brightest guy in town on this topic.”

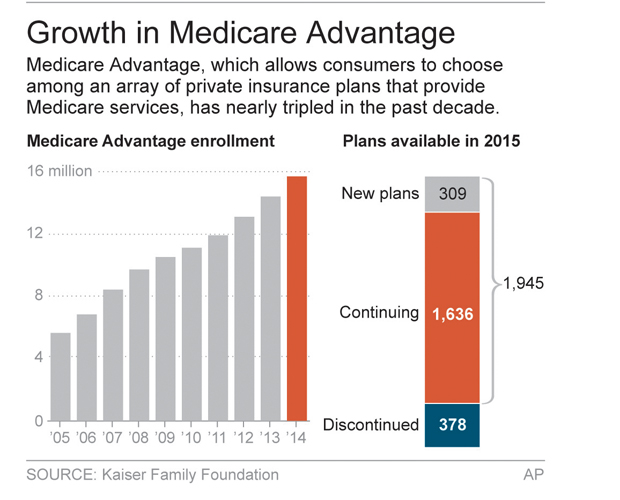

Ryan, the GOP’s de facto policy director, used his perch as House Budget Committee chairman to commit House Republicans to changing Medicare’s structure for people younger than 55. In his plan, people could choose between the traditional Medicare program and subsidies for a private plan, while private insurers would bid to provide the service. Ryan, who now is chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, also worked a version of the proposal into the Romney-Ryan 2012 campaign.

Guarding the third rail

Josten says he began seriously pushing the case for entitlement reform in 2013, giving a speech to regional Chamber heads in September meant to raise awareness of the scale of the problem.

“I’m the recipient of hate mail, man. I didn’t propose a thing,” Josten said. “You’re attacked the minute you open your mouth.”

What can be openly discussed about Social Security and Medicare — the “third rail” of politics — is closely policed. Neither party can resist an opportunity to scare voters about the possibility that the other party might slash grandma’s Social Security check or mess with her Medicare plan.

When Ryan’s Medicare plan was first passed by the House in 2011, a liberal advocacy group called the Agenda Project ran an ad featuring a Ryan lookalike throwing granny off a cliff. The ad went viral, and the group launched similar attacks in the presidential election and on Ryan’s book promotion tour.

“You will see a lot of granny in the next two years,” promises Eric Payne, founder of the Agenda Project. “We’re gonna have a lot of fun with her. And the Republicans are not going to have fun.”

For the most part, the Left is on the same page as the retirees lobby group, the AARP. With 37 million members aged 50 or more, the AARP is opposed to benefit cuts in any form to retirement programs. That’s a powerful force.

AARP will press presidential candidates to promise that they will not cut Social Security benefits, says AARP legislative counsel David Certner.

Social Security, as far as the AARP is concerned, is a self-financed, off-budget program. It has enough money in its trust fund to pay full benefits through 2033.

Congress will have to change the program to keep full benefits after that, Certner concedes, but it’s a “relatively easy to fix in terms of making the math work out.”

The group isn’t calling for specific tax hikes to raise money. It will ask presidential candidates to push their own plans for extending the program’s solvency. “We’ve been trying to basically encourage the debate,” Certner explains.

As for Medicare, “there’s probably some agreement between us about holding down the rising cost of health care,” says Certner. “But we remain opposed to simply shifting higher costs onto seniors,” he says, arguing that the Ryan plan for people over age 55 would do just that.

Obama declares victory

These days, Obama is not too far from the AARP position.

At the height of the clash between his administration and the GOP in 2011, Obama put spending reductions on the table, including a new way of calculating inflation. This method, known as chained CPI, is thought to capture changes in prices by accounting more realistically for people switching away from goods and products when their cost is greater. Chained CPI shows inflation to be lower than the current method of calculation, and it would thus cut benefits and increase taxes by $340 billion over 10 years, according to the CBO.

As the annual deficit has fallen from more than $1 trillion to under $500 billion, however, President Obama has back-tracked from chained CPI, which was always represented as a negotiating concession, not a policy preference.

The Obama administration has also all but declared victory in reducing Medicare spending.

Obama economic adviser Jason Furman in April touted the recent slowdown in health care spending growth as “one of the most under-told stories” of our time, comparing it to the fracking revolution.

The last three years for which there is data – 2011, 2012 and 2013 — are the three years with the slowest growth in national health care spending since records were first kept in 1960.

Altogether, the CBO expects the government to spend roughly $700 billion less through 2020 than it projected in 2010, before the enactment of Obamacare and its expansion of federally subsidized health insurance.

There is debate among economists over what is behind the slowdown in the growth.

Obama’s economic advisers say the slowdown has been driven by the 2010 health care law, and that in particular its cuts to providers and reforms to the Medicare payment system have driven down government spending. But health care spending often changes with the economy, and the decline in growth coincided with the recession.

The challenge

But the Chamber says the fiscal future is bleak even if health care spending growth remains low.

The president’s budget includes another $400 billion in Medicare spending reductions, including more provider cuts.

If the payment reforms included in the budget and in Obamacare work out, the “potential implications for the budget deficit and for American well-being and health going forward are enormous,” Office of Management and Budget Director Shaun Donovan said in April.

Josten dismisses this as wishful thinking. “They’re kidding themselves. Does anybody in the country think you can solve a $40 trillion problem by screwing hospitals and doctors and clinics?”

Nevertheless, the Chamber is interested in supply-side reforms the White House is pursuing, and in overhauling the system to pay more for health outcomes rather than for each procedure or hospital stay, or in investing in research that could lower costs.

In particular, Josten cites projections that without action there will be 13.5 million people suffering from Alzheimer’s disease by mid-century compared to 5.1 million today. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that the government spends one in five Medicare dollars on treating the disease and will spend $14 trillion on it and other dementias through 2050.

Josten says former House Speaker Newt Gingrich helped shape his thinking on the issue: If the government invests in brain research that leads to better treatment for Alzheimer’s, that alone could significantly ease the country’s fiscal burden.

Alzheimer’s research is an “enormously rational investment,” says Gingrich, offering as evidence the fact that the government no longer pays for iron lungs thanks to the polio vaccine.

“The challenge the Chamber has is it’s a very large organization with a very complicated decision process,” Gingrich says. He later explains that “they generally favor innovation and they generally favor thinking about these things. But I don’t think they’ve put muscle into it at this phase.”

Where the Chamber is best positioned to exert influence is on legislation that has already been written. A measure like the Ryan plan, Josten says, is necessary for Medicare simply because of the costs associated with demographic change.

Even if the White House’s sunny optimism on health care costs proves well-founded, federal debt would continue to be a problem and programs favored by businesses would continue to feel the squeeze.

It would take unthinkably huge tax increases to close the gap.

For instance, one popular proposal among Democrats is to remove the upper limit on earnings subject to the Social Security payroll tax, currently set at $118,500 a year.

This would eliminate only two-thirds of the expected shortfall in the Social Security trust fund, according to the Social Security Administration. Raising the cap to the level at which 90 percent of all earnings would be subject to the tax, another popular proposal, would close one-third of the gap.

Lifting the cap polls well, unlike raising the retirement age. But it wouldn’t just affect wealthy earners. A married single-earner couple earning $125,000 a year would see their total federal marginal tax rate rise from about 33 percent to 45 percent, according to calculations from the conservative Heritage Foundation, an increase of roughly half.

“A trillion-dollar tax increase on middle-class families” is how the idea to lift the earnings cap was described by Hillary Clinton on the campaign trail in 2007.

Whither progressives

Clinton, the heavy favorite to win the Democratic nomination for 2016, has not said whether she still opposes lifting the cap.

She will face a significant progressive campaign, however, pressing her to endorse not cutting Social Security, but expanding it.

Liberal Democrats in Congress, such as Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio, have backed expanded Social Security to get the Democratic nominee to sign on to this viewpoint. They have been aided by outside groups such as the Progressive Change Campaign Committee.

On the other side of the political spectrum, Republicans with whom the Chamber usually aligns are resistant to tax increases of any kind.

As the party has been influenced by the Tea Party in recent years, it also has become, on balance, more willing to embrace the spending cuts to domestic and defense programs that might have proved too much for the GOP of the Bush years.

Although spending caps are hated by defense contractors and hawks within the GOP, a significant portion of the party is comfortable with them.That’s partly because some of the Right’s intellectual leaders view caps or across-the-board sequestration cuts as a major blow for fiscal rectitude.

Grover Norquist, president of the influential activist group Americans for Tax Reform, calls the caps a “gift from the gods during the otherwise bleak Obama administration.”

If Obama were to offer entitlement reforms to reduce spending by much more than the caps would be raised, then Republicans could consider a deal, Norquist says. But otherwise, “it would be a very bad thing to lighten up on the pressures” created by the caps.

There will be plenty of outside pressure on congressional Republicans to keep the caps in place.

Freedom Partners, an important group that is part of the political network backed by businessmen Charles and David Koch, is engaged in making sure that Republicans raise the spending caps only if there’s a “legitimate replacement” for the cuts, says senior policy adviser Andy Koenig. “We are going to be very much engaged in making sure they don’t break the promise they made on the spending caps.”

The fate of the caps on discretionary spending, set at $523 billion for defense and $493 billion for everything else for fiscal 2016, will be a major plot line in congressional action between now and October, when the fiscal year begins.

Obama staked out his negotiating terms early in the spring: He won’t sign spending bills that don’t raise the caps. His administration is open, however, to a deal in which both the defense and non-defense caps are raised by equal amounts and offset by reductions to future spending. That was the basic template of a deal struck between Paul Ryan and then-Democratic Senate Budget Committee chairwoman Patty Murray of Washington in late 2013.

That deal helped assuage concerns of spending being cut too deeply over the past two fiscal years.

With the deal set to run out and a new round of sequestration in store, however, the shifting ideological landscape has left the Chamber and businesses more generally in an odd position. The group shares the White House’s goal of easing the spending caps and consequently is even more eager than many in the GOP for large-scale entitlement reform.

“This is the most predictable and the most singularly quantifiable economic crisis this country has ever seen coming,” Josten says of entitlement spending. “And what I think concerns the business community more than anything else is: You can see it coming.”