Nothing gets people talking about the presidency like an election year. For months, the country debates which candidate would make the best or most effective leader. The present election cycle has taken this dynamic to new extremes because President Trump has either saved or destroyed the presidency, depending on who you ask.

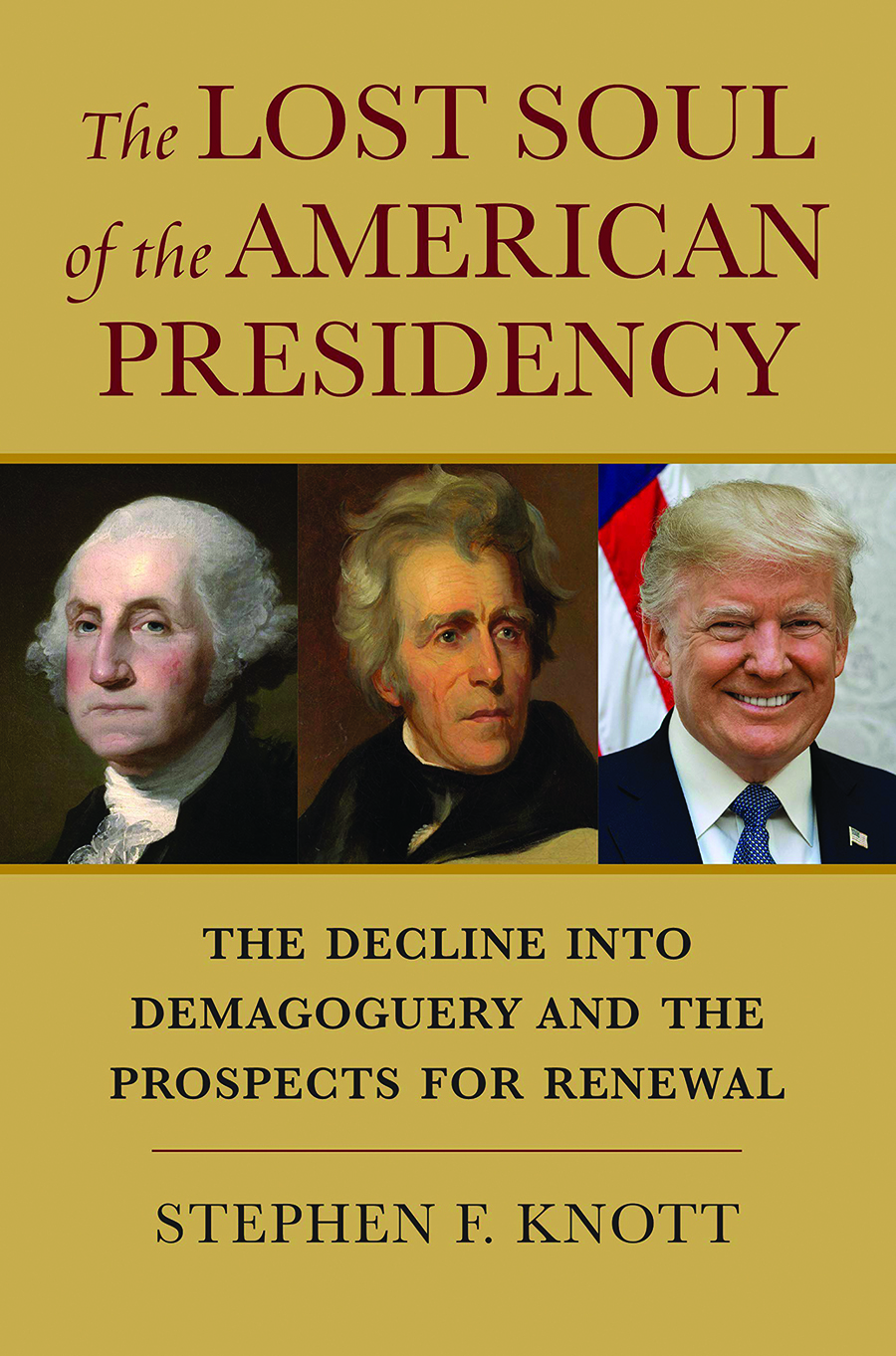

Into this fray comes Stephen Knott’s new book, The Lost Soul of the American Presidency. Knott, a presidential scholar with an affinity for George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, uses the standards set by these men as a jumping-off point to explain what he calls the presidency’s “decline into demagoguery.”

Knott’s book is a familiar tale of how the presidency envisioned by the Founding Fathers was degraded by populist and progressive alternatives. But Knott takes this argument further than most. In fact, he idealizes Washington to such an extent that he makes the decline of the presidency seem inevitable and its renewal unlikely.

As Knott describes in fine detail, the founders intended for the presidency to inspire the nation and bring it together. This would require a president with the ability to rise above and occasionally go against the tide of public opinion.

Knott argues that this original vision was quickly undermined by Thomas Jefferson, who inaugurated a more populist presidency with his Revolution of 1800. Knott faults Jefferson for practicing what Hamilton, in Federalist 68, called “the little arts of popularity” — encouraging political attacks on his opponents to rile popular passions and letting those passions direct the policies and tone of his administration.

Jefferson’s populism, Knott argues, paved the way for the even more demagogic presidencies of Andrew Jackson and Andrew Johnson. Knott credits Johnson with sweeping away the last vestiges of the founders’ presidency. Instead of practicing prudence and unifying the nation, Johnson traveled the country to promote his policy agenda, pushing conspiracy theories and calling for the deaths of his political opponents, whom he considered traitors. According to Knott, Johnson “razed with a certain amount of glee” the “dignified presidency” envisioned and established by the founders.

From that point, it was easy for men such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson to build up a “progressive” presidency in which presidents didn’t just follow popular opinion but attempted to change it. With few exceptions, every president since Wilson has embraced this idea of “presidential government.”

Knott goes beyond the usual paeans to Washington and shows precisely how our first president worked to enact Hamilton’s conception of the office. Particularly interesting is Knott’s contention that Washington’s love of the theater shaped his actions as president, especially his grand tours of the country. As part of the “elaborate choreography” of these tours, Washington would switch between simple dress and military grandeur, depending on which mode he thought would best inspire his audience.

Still, there are some problems with Knott’s account of the presidency and its ultimate demise. At various points, he refers to his executive ideal as “the Founders’ presidency,” “the Framers’ presidency,” and the “Hamiltonian presidency,” but only the last of these is fully accurate. Jefferson, though he opposed Washington’s and Hamilton’s approach to presidential leadership, was nonetheless a founder. Knott portrays him as little more than a snake in the garden.

The problem with this interpretation is that Jefferson had to practice “the little arts of popularity” if he wanted a chance at the presidency. To imply that Jefferson should have avoided political attacks on the Federalist majority in 1800 is tantamount to implying that he should have stayed at Monticello and left the Federalists unopposed.

Knott’s flawed indictment of Jefferson serves as the shaky foundation for his narrative of decline. He says that the degradation of the presidency was “altogether avoidable” and was “hastened in good measure” by Jefferson’s actions. But to say that it was “avoidable” is to deny the fractiousness that characterized the early republic.

While Knott sees the Revolution of 1800 as a departure from the founding, many others have seen it as a return. As early as 1806, the Antifederalist writer Mercy Otis Warren worried that “the progress of the American Revolution has been so rapid … that the principles which animated to the noblest exertions have been nearly annihilated.” Warren applauded Jefferson for defending the founding principles from what she viewed as a Federalist attack.

This is not to say that the Jeffersonian vision is correct but simply that the principles of the founding were more ambiguous than Knott admits. What Lance Banning has called “the Jeffersonian persuasion” has always been present in politics, and the Federalists do not have a monopoly over the “soul” of the presidency.

In some ways, denying the political realities of the founding sets an impossible standard for presidential greatness. Knott reserves his highest praise for Washington and Abraham Lincoln, both “great-souled” men who rose above politics in extraordinary times.

This focus on Washington and Lincoln distracts from the best parts of the book, which argue for a redefinition of presidential greatness. Knott rightly criticizes Wilson for dismissing every president from Lincoln to Roosevelt as “mediocrities” and condemns historians such as Arthur Schlesinger for enshrining this attitude in the academy.

Yet Knott spends no time discussing the presidents he tells us are so egregiously overlooked. He does offer brief praise for William Howard Taft, Gerald Ford, and one or two other presidents who, in his telling, embodied prudence and statesmanship. But one wishes he would give a fuller account of their virtues, particularly in light of his call for “a new Mount Rushmore” composed of presidents who upheld the founders’ vision for the office but didn’t necessarily make history.

As Knott himself demonstrates, men like Washington and Lincoln don’t come around often. Perhaps the first step toward saving the soul of the presidency is for historians to turn their attention away from the giants of history and toward the virtues of the Oval Office’s forgotten occupants.

Tim Rice is a writer and editor based in Washington.