Any magician can tell you when he or she was first bitten by the magic bug. For me, it was on a childhood trip to Disney World where I witnessed a street magician perform an absolute miracle, effortlessly linking and unlinking large metal rings, solid steel melting through solid steel. The feat was all I could talk about for the rest of the day, my imagination running wild with possibilities for how it could be done, each of them completely implausible and off the mark.

Back home in Texas, I insisted my parents take me to the local magic shop, where I picked up a bevy of trick cards, silks, and false appendages. But the linking rings, selling for $20 or so, were beyond my means on that first visit. And no matter how I entreated the proprietor to tell me how they worked, he wisely refused. If I wanted to know, I’d have to work on the tricks I’d purchased, save up my allowance, and come back.

There were two lessons here. One was that the secrets of magic were not to be given freely. They had to be earned — or at least bought. The second, discovered when I eventually returned to purchase a set of linking rings, is that a secret learned without context can be shockingly disappointing. The method was far simpler than the far-fetched ideas I’d imagined. The secret by itself was rubbish. It was only when embedded in an elaborate routine, with careful handling and thoughtful presentational subtleties, that it could inspire wonder.

Those lessons are harder to come by today, when any adolescent with a smartphone can look up the method to countless tricks on YouTube. Magicians can hardly blame them for wanting to look. It’s our job to make you curious. But such exposure is typically quick and dirty, engendering no real appreciation for the art.

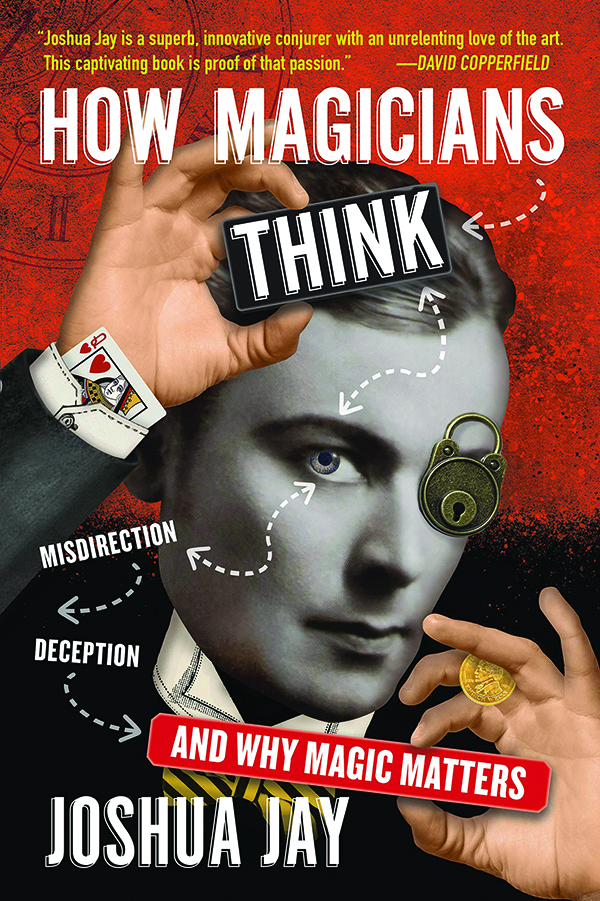

By its very nature, magic is uniquely difficult to discuss with nonpractitioners without giving away the very secrets that make it work. The challenge of doing so is taken up by Joshua Jay in his new book How Magicians Think: Misdirection, Deception, and Why Magic Matters. An accomplished professional performer, Jay has written this book explicitly for laymen, and there’s barely a secret in sight. Methods are mostly referred to obliquely, with only a few minor exceptions revealed to illustrate a larger point. Instead, in 52 short essays, he answers the questions he’s often asked about how magic works and what it’s like to be a magician. Questions such as: What do you do for a living? What’s the weirdest show you’ve ever done? And why do some people hate magic?

“Too many of us watch magic shows to figure out how the tricks are done,” Jay writes in the introduction. “As you’ll learn, that mindset is a trap. While you’re busy trying to find the solution to an illusion, you miss what is in plain sight: artistry.”

Artistry, to be fair, is often lacking in the average magic show. Jay acknowledges upfront that most audiences have never witnessed truly excellent magic and that mediocre performances have lowered expectations of the art. “Every time I walk on stage,” he writes, “I’m fighting a percentage of the crowd who dislike what I do based on what others have done.” Contemporary cultural touchstones for the role of magician are as likely to be the fictional, pompously inept character Gob Bluth from Arrested Development as they are a real-life great such as David Blaine.

Like any worthwhile pursuit, the appreciation of magic is enhanced when one knows a little of the workings, if not specific methods. Without giving too much away, Jay dives into what makes a great trick. It shouldn’t be “too perfect,” which can paradoxically tip audiences to the only possible method: a stooge in the crowd, a duplicate card. Ideally, a well-crafted routine cleverly plays with the audience’s expectations, opening doors to possible methods and then subtly proving them false, leaving spectators with no route to backtrack. And the plot should be surprising and unexpected, but not just a series of random events — a great trick needs a satisfying internal logic that motivates a successful conclusion.

In a book written for magicians, these principles would be implicit in the detailed explanations of specific tricks: how to do a sleight, the reason to perform it at a certain instant, the presentation that misdirects attention at the precise moment. In How Magicians Think, Jay instead explores them through magic’s greatest performers, with essays dissecting the work of Blaine as well as David Copperfield and Penn and Teller, and introductions to prolific creators of who have never headlined a Las Vegas stage or scored a TV special. One of the most influential magicians of the past 40 years was Simon Aronson, a real estate lawyer in Chicago who in his spare time published massive tomes of transformational card magic. Jay only hints at the precise nature of Aronson’s contributions to the field, but if not for his writing, a person would be unlikely to glimpse this side of the magic world at all.

When Jay does peel back the curtain to reveal a few secrets, it’s unsurprising that Penn and Teller tend to be involved. The “bad boys of magic” famously violated norms against exposure, riling up London’s stuffy Magic Circle and provoking at least one American magician to throw a punch. In “Cups and Balls and Cups and Balls,” they perform the classic routine of balls vanishing and reappearing under three inverted cups. Then they repeat the trick with clear plastic cups that show exactly when every move occurs. Unlike cheap exposure that demeans the art, Penn and Teller’s lesson in choreography invites the audience to appreciate it at a deeper level. “The audience’s best interest is most often served by not knowing how something is done,” Teller reflects in the book. “But here and there, part of the delight is being taken on a backstage visit that is enchanting and beautiful.”

“Beauty” isn’t a word typically associated with magic performance, which is often approached with detached irony, mockery, or the question every magician has heard a million times: “Do you do kids’ birthday parties?” The subtitle of Jay’s book, “why magic matters,” acknowledges that the case for taking magic seriously needs to be made, not taken for granted.

Yet all magicians can also recall moments of pure wonder, whether in their own pasts, the faces of their spectators, or in stories shared by enthusiastic laymen. When someone experiences a feeling of true astonishment, he or she remembers it for years. These are the experiences that make all the lonely hours of endlessly practicing a move in front of a mirror worth it.

Jay recounts one such moment from his first book tour when he shared a stage with authors writing about heady topics such as the war in Afghanistan and living with cancer. He was there to do tricks and judge the pumpkin carving contest, which could have felt trivializing. But there was one child, a cancer patient himself, who couldn’t get enough of the magic. Jay asked him why he kept asking for more. “Because I’m in and out of a hospital all the time,” the child said. “I’m a full-time patient. When we’re doing magic, I feel like myself.”

The “we” was the part that stood out, a reminder that the best magic isn’t performed at or to an audience, but with them. It’s a dance. “There isn’t a magic effect unless someone is there to experience it,” Jay writes. “If you’re doing magic alone, you’re just practicing.” No matter how skilled the magician, the feeling of wonder ultimately depends on the audience’s receptiveness to experiencing it.

As with other performers, magicians have been robbed of the opportunity to share these moments for much of the pandemic. It’s hard to pick a card while social distancing. Virtual shows have helped fill the void, but there’s no substitute for a hands-on, close-up performance. As the world reopens and live entertainment returns, there is an opportunity for magic to be welcomed as more than a mere amusing distraction at cocktail parties. How Magicians Think won’t teach readers how to do a card trick, but it may leave them more open to experiencing magic when the opportunity arises.

Jacob Grier is a moderately successful professional writer and a less successful amateur magician in Portland, Oregon.