The pension fund for the Teamsters, one of the nation’s largest labor unions, is telling its participants that their benefits soon will be cut because of the fund’s dire financial condition.

Thomas Nyhan, executive director and general counsel for the Central States Pension Fund, sent out a “dear participant” letter last month explaining that the multi-employer pension fund is “in critical and declining status.”

The fund’s trustees, Nyhan said, will take advantage of the recently passed Multi-Employer Pension Reform Act, which allows them for the first time to cut benefits. The move follows years of stepped-up government lobbying by the union following the 2008 recession, which the pension funds’ trustees largely blame for its financial woes.

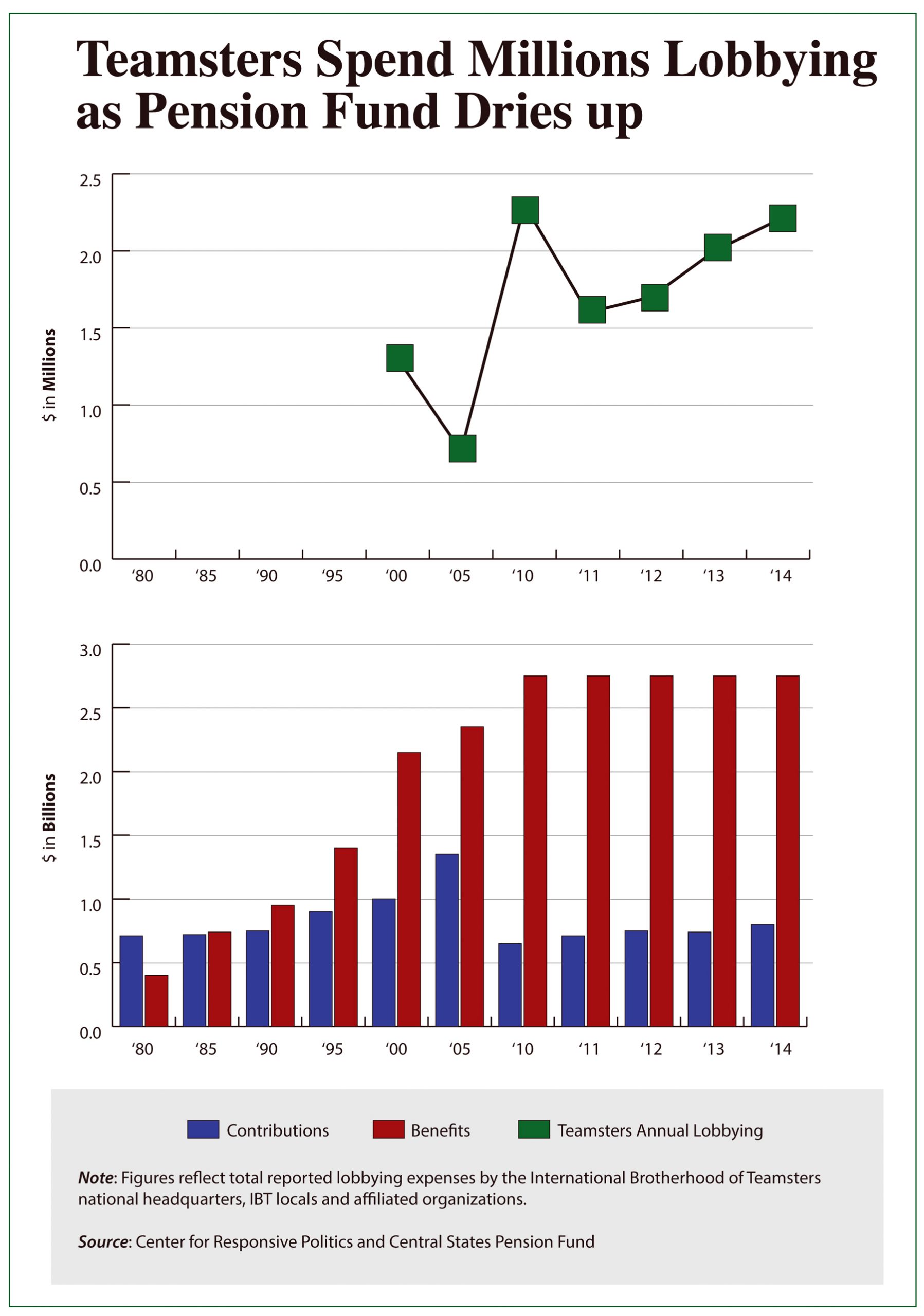

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters has spent almost $13 million lobbying Washington since the recession and more than $2 million in 2014 alone, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics.

The Teamsters officially opposed the pension reform bill. “Our union has been on record from the start — we are opposed to any legislation that permits the suspension or reduction of accrued benefits,” Teamsters President James P. Hoffa said in a statement to the Washington Examiner.

The pension fund’s eight trustees are evenly split between local union officials elected by rank-and-file members and business representatives, according to Teamsters spokesman Galen Munroe. He added the pension fund operates independently of the union.

A dissident group, Teamsters for a Democratic Union, says Hoffa’s opposition was just for show and the union backed the bill all along. The group notes that the National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans, which includes Hoffa as a board member, endorsed the legislation.

On Wednesday, the group posted a leaked October email reportedly from Nyhan to a person at the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation regarding the Teamsters’ opposition.

In the email, Nyhan said of the union, “I do not believe they are planning on dispatching any troops to the Hill or making any visits [to lobby lawmakers] but simply writ[ing] a letter they will likely post on their website … a true profile in courage.” The letter was posted under the headline, “Leaked Email Exposes Hoffa’s Support for Pension Cuts.”

A Teamsters for a Democratic Union representative did not respond to a request for comment.

In the April notice to plan participants, Nyhan said, “Our board of trustees is currently considering how such benefit reductions could be implemented fairly.”

He did not say how deep the cuts might go, stating that the trustees expect to provide more specific information “sometime this summer.” The fund covers 400,000 of the Teamsters’ 1.4 million members.

The move could be the first of a wave of union pension funds taking advantage of the pension reform law, which President Obama signed on Dec. 16.

The Labor Department currently lists 35 union pension plans as being “endangered,” meaning they lack the assets to pay 85 percent of their projected liabilities. Another 51 are in “critical status,” meaning they cannot pay 65 percent of projected liabilities. Five of the critical ones are other Teamsters plans.

Diana Furchtgott-Roth, senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute and co-author of Disinherited: How Washington Is Betraying America’s Young, predicted that many would follow the Teamsters’ example.

“These plans’ deficits are unsustainable and hurt young workers, who are paying for programs that won’t be there when they retire,” she said.

The shortfalls could get worse. Multi-employer pension funds like the Teamsters’ pool together contributions from different employers. Anytime a business fails, the remaining employers are legally obligated to pick up the slack.

Labor organizations argue the funds are more secure as a result. The funds have the added benefit of tying the worker’s retirement to their union, not their company, and thus help labor organizations retain members when workers change jobs.

Troubled multi-employer plans can drag down otherwise healthy companies, though. If many others in the system go out of business, it raises the pension costs for the ones that remain.

The bipartisan reform law, written by Reps. John Kline, R-Minn., and George Miller, D-Calif., allows pension plan trustees to reduce benefit payments as part of a restructuring plan. Even participants with vested benefits could see reductions, which previously had been prohibited.

The law covers an estimated 1,400 multi-employer pension plans with about 10 million participants.

Several labor organizations, including the Service Employees International Union and United Food and Commercial Workers, backed the legislation.

They did little to highlight it, though. Unions had previously sought legislation to bailout out troubled plans but lawmakers had little appetite for it. Trimming benefits was a fallback position.

The Teamsters’ Central States Pension Fund is one of the most troubled. It currently has $17.8 billion in assets but is obligated to pay out an estimated $35 billion in benefits.

Since 2010, it has paid out about $2.8 billion to recipients annually, but taken in just $750 million each year in contributions. About 1,500 employers contribute to the fund.

The fund now has three times as many retirees as active members. “For every $3.46 that the fund pays out in pension benefits, only $1 is collected from contributing employers, which results in a $2 billion annual shortfall. Clearly, that math will never work,” the pension fund’s website points out.

The problem has been ongoing for several years. Fund actuaries first told the Labor Department in 2009 that it was in “critical status.”

The trustees blame the shortfall on a spike in retirements from the Baby Boom generation as well as the 2008 recession, which drove down the fund’s investment assets and pushed many companies into bankruptcy.

Even before the recession, the United Parcel Service, a former participant in the Central States Pension Fund, was so worried about its potential future liability that in 2007 it a struck a deal with the Teamsters to be allowed to withdraw from the fund in exchange for a one-time payment of $6.1 billion.