An already overburdened and backlogged federal court system got worse during the coronavirus pandemic, prompting some legal experts and lawmakers to call for an expansion of the judicial bench.

And unlike the deeply divisive idea of packing the Supreme Court with more justices, there’s some bipartisan agreement that lower-court federal judges are overworked and need help presiding over their growing caseload.

The Washington Examiner spoke with several attorneys who said the pandemic had a significant impact on delaying cases, compounding the large uptick in pending civil cases.

“Backlogs have always been an issue in the civil court system, but they became especially pronounced following COVID,” said Evan Walker, owner of a legal firm in La Jolla, California.

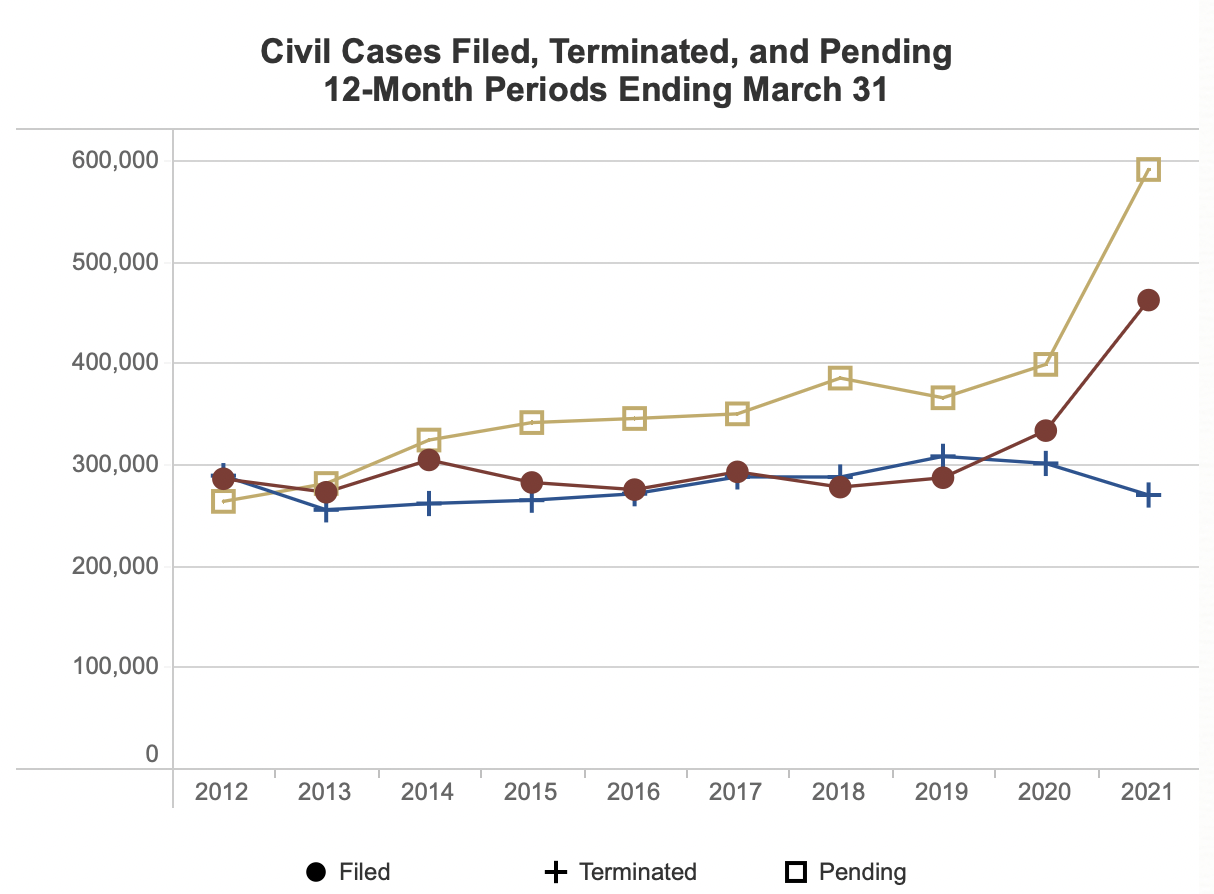

In 2020, there were 397,492 pending civil cases filed in federal court. By 2021, the figure spiked to 590,288 pending civil cases, marking a nearly 49% change in one year, according to official U.S. federal judicial caseload statistics.

During this period, the COVID-19 pandemic affected the workload of almost all components of the federal judiciary, resulting in the shuttering of some federal courthouses and the reliance on electronic methods to conduct proceedings. The adaptations were not seamless and had the effect of delaying justice.

STUDENTS SUFFER LARGEST LEARNING LOSS IN 30 YEARS AFTER PANDEMIC SCHOOL CLOSURES

“Not only court employees, but also attorneys and others making use of the courts had to acquire new skills and equipment to handle judicial work remotely,” according to a 2021 U.S. federal court report on judicial caseloads. “Many persons who otherwise would have become involved in litigation or other proceedings during the pandemic likely were unable or unwilling to do so.”

Texas-based personal injury attorney Dr. Louis Patino said delays in civil court trials were compounded because most courts place a higher priority on criminal cases due to the Constitution’s promise of a right to a speedy trial. Still, the number of pending criminal cases has also seen a 6% increase between 2020 and 2021, from 110,115 pending cases to 114,174.

“Getting a trial date in many courts is difficult, and even if we are fortunate enough to have a trial date on the court’s docket, the chances of that trial date being reset is very high,” Patino added.

While increasing the size of the federal judiciary has been common throughout U.S. history, with nearly 30 expansions since 1891, the last meaningful expansion happened in 1990, when Congress added 11 more circuit court judgeships and 61 more district court judge seats.

In the years since, the federal judiciary has become increasingly political, as presidents are granted responsibility to appoint judges and have used that ability to stack the roster with individuals who align with their ideologies.

Thomas Berry, a research fellow at the Cato Institute, wrote that the “clear culprit” of the clogged and overgrowing caseload phenomena is the “increasingly polarized and partisan judicial confirmation process” in an August 2021 report on the matter.

“I think there’s no disputing that the drought we’re in between bills to create new judgeships is unprecedented. And so, when you just consider the basic fact of population growth, it just doesn’t make sense that the number of, especially appellate judges we had in 1991, is still an appropriate number for 2022,” Berry told the Washington Examiner in a phone interview.

Last year, Sens. Todd Young (R-IN) and Chris Coons (D-DE) introduced the Judicial Understaffing Delays Getting Emergencies Solved Act, or the JUDGES Act, which would create 77 new district court judgeships by 2029 — half after the 2024 presidential election and half after the 2028 election. But so far, the current Congress has yet to hold a vote on the passage of the legislation.

Berry supports this “staggered approach” of allocating new judicial vacancies following each presidential election as a means to eliminate concerns that one party’s president would have an unfair advantage to reshape the federal judiciary.

But passing such legislation would mean both Republicans and Democrats would essentially be “settling for half a loaf instead of a chance at a full loaf.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“My hope. I don’t know if this is realistic, is that as we go longer and longer without either party being able to muster majority to pass a new judgeship bill … that both parties will realize the only option for new judgeships is some kind of staggered bill,” Berry said.

“But we’re going on 30 years now, and that still hasn’t happened, at least at the circuit court level,” Berry added.