The bond between fathers and sons is a powerful one. The love and adoration they feel for each other are undeniable, and sons often want to walk in their father’s footsteps. Living in the shadow of a famous father, however, can be hard. In the case of Winston Churchill and his only son, Randolph, the relationship was equal parts loving and difficult. Expectations were impossibly high, and disappointments were inevitable. As it turned out, Randolph supplied the latter in spades.

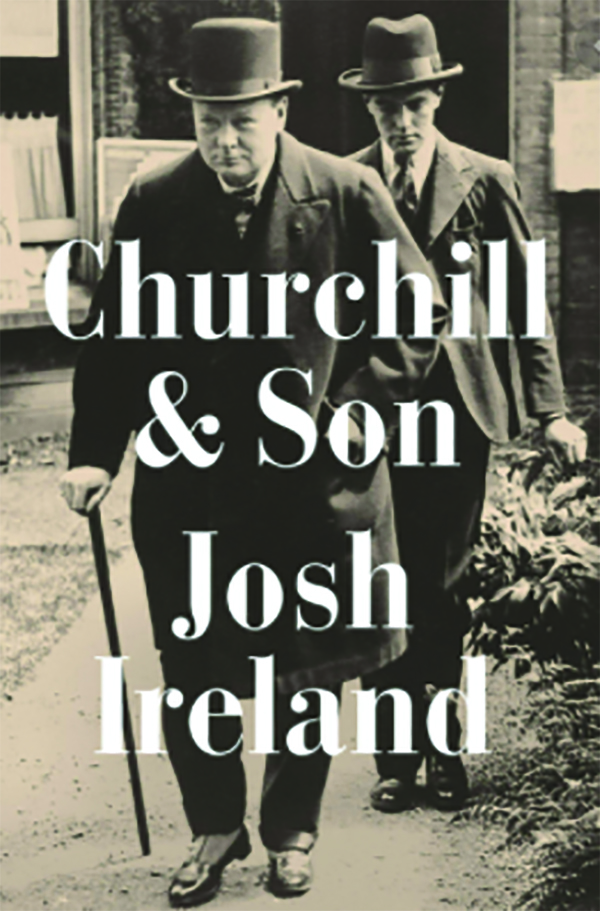

Josh Ireland’s Churchill & Son is a masterful examination of this complex father-son dynamic. Ireland sees in Winston a father “obsessed with his son” but also “consumed by his own sense of destiny, his belief that fate had singled him out for a higher purpose.” In Randolph, he observes a doting son “whose loyalty to his father was so extreme that it came to hinder almost every aspect of his existence.” And while the Churchill men regularly tried to make their differences complement each other, they often seemed to go together like oil and water.

For Winston, this was a case of history repeating itself. He had had a tenuous relationship with his own father, Lord Randolph Churchill, whose promising political career was cut short after he fell out with the Tory leadership. According to Ireland, Winston “never stopped thinking about the man he had hero-worshipped ever since he was a boy.” He memorized his father’s speeches, learned the art of politics at his idol’s feet, and eventually followed Lord Randolph’s lead and became a “Tory radical” in Parliament, albeit after spending two decades as a Liberal. “The problem,” Ireland writes, “was that while he was alive, Lord Randolph barely spared his son a second glance.”

It was Lord Randolph’s untimely death in 1895, when Winston was only 21, that made Winston want to do better when he became a father. Churchill & Son shows how the future prime minister set out to do things differently with young Randolph (born 1911), the second child from his marriage to Clementine Hozier. Winston “adored” being a father and made sure his family took priority in his busy life and schedule. In turn, “Randolph more than any other child idolized Winston,” and there were times he could “barely contain the pride he felt at having such a man as his father.”

Winston wasn’t a carbon copy of his distant father. He actually “cared what happened to Randolph in a way Lord Randolph never had” about him. But he was also a driven, highly intelligent public figure who could be difficult to relate to. There was his “relentless egotism, his abrasive way of forcing his arguments onto others, and his inability to resist meddling in everybody else’s business,” which often frustrated colleagues and allies. Winston’s passion for politics, hunting, polo, and dining with colleagues and friends also pulled him in many different directions, so much so “that for the first few years of Randolph’s life, even when they were under the same roof, he and his father existed in almost completely separate worlds.”

This absence wasn’t lost on his son, who lashed out. Randolph was “free to terrorize his siblings and cousins” and did so with great zeal. He disliked attending Eton College and called himself a “misfit” as well as a “rebel and a loner” like his father (which may have been an exaggeration). He was unpopular, constantly in trouble with his teachers, and, by his own admission, a “lazy” student. He expressed a casual “indifference to punishment” and “disregard of consequence, that went beyond high spirits and landed somewhere less innocent.”

In fairness, there were good moments. The son transformed into a miniature version of his father. They both loved “the pugnacious back-and-forth of good conversation; using words to dominate the room; watching how they could change its atmosphere; knowing that argument could be a source of pleasure.” In fact, argument pleased both Churchills to no end and gave them the ability to discuss just about anything. Ireland reflects on a poignant moment at the end of a long conversation between Winston and Randolph in the 1920s, at the end of school holidays. The father turned to his son and sadly told him, “You know, my dear boy, I think I have talked to you more in these holidays than my father talked to me in the whole of his life.”

Little wonder, then, that Winston wanted and expected so much from Randolph. He saw his son’s ability and intelligence, including his writing and oratorial skills, and wanted to help nurture them. He spoiled Randolph, showering him with praise and compliments and caring not a whit about his son’s arrogance, abrasiveness, and seemingly limitless ability to “send his elders into paroxysms of rage.”

Unfortunately, Winston’s decision to ignore rather than correct Randolph’s traits led to significant problems as the latter reached adulthood. Randolph’s interest in education waned, and he dropped out of Oxford after only a year. He gambled and drank to excess. He had thoughts of suicide. He flitted from woman to woman. As a young man, he had expected eventually to become prime minister like his father, but he was mostly a failure in politics, only winning a seat in Preston in 1940 because he ran unopposed. Well into adulthood, Ireland observes, Randolph was “too often angry, too often drunk, too often gratuitously offensive” to look at life, family, marriage, and career in a patient manner. (The novelist Evelyn Waugh, who served with Randolph in World War II, apparently spoke for many when he described him as a “flabby bully” and a “bore” with “no intellectual invention or agility.”)

Randolph’s irresponsibility led to strains in the father-son relationship that carried on for years. Some of the tension subsided when Winston chose Randolph to be his official biographer, impressed by his son’s superb book about the life and career of Lord Derby. “The thought that Randolph would be [the biography’s] author had been on Winston’s mind for a long time,” Ireland writes, “perhaps even before his son had been born. And Randolph fervently wanted the chance to write his father’s story, just as Winston had before him.” This decision, made in 1960, created a final chapter of relative bliss between father and son. Winston died in 1965. Randolph, his health ruined from years of heavy smoking and drinking, died three years later, having completed only two of the planned five volumes on his father.

“Fathers always expect their sons to have their virtues without their faults,” Winston said to Randolph and one of his sisters, Sarah, in November 1947. This line, according to Winston, had been spoken to him by an apparition of Lord Randolph, who appeared to his son one foggy evening as he painted his father’s portrait. Randolph certainly disappointed this expectation, displaying most of his father’s faults with few of his virtues. But with a father such as Winston Churchill, there may have been no other path to follow.

Michael Taube, a columnist for Troy Media and Loonie Politics, was a speechwriter for former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.