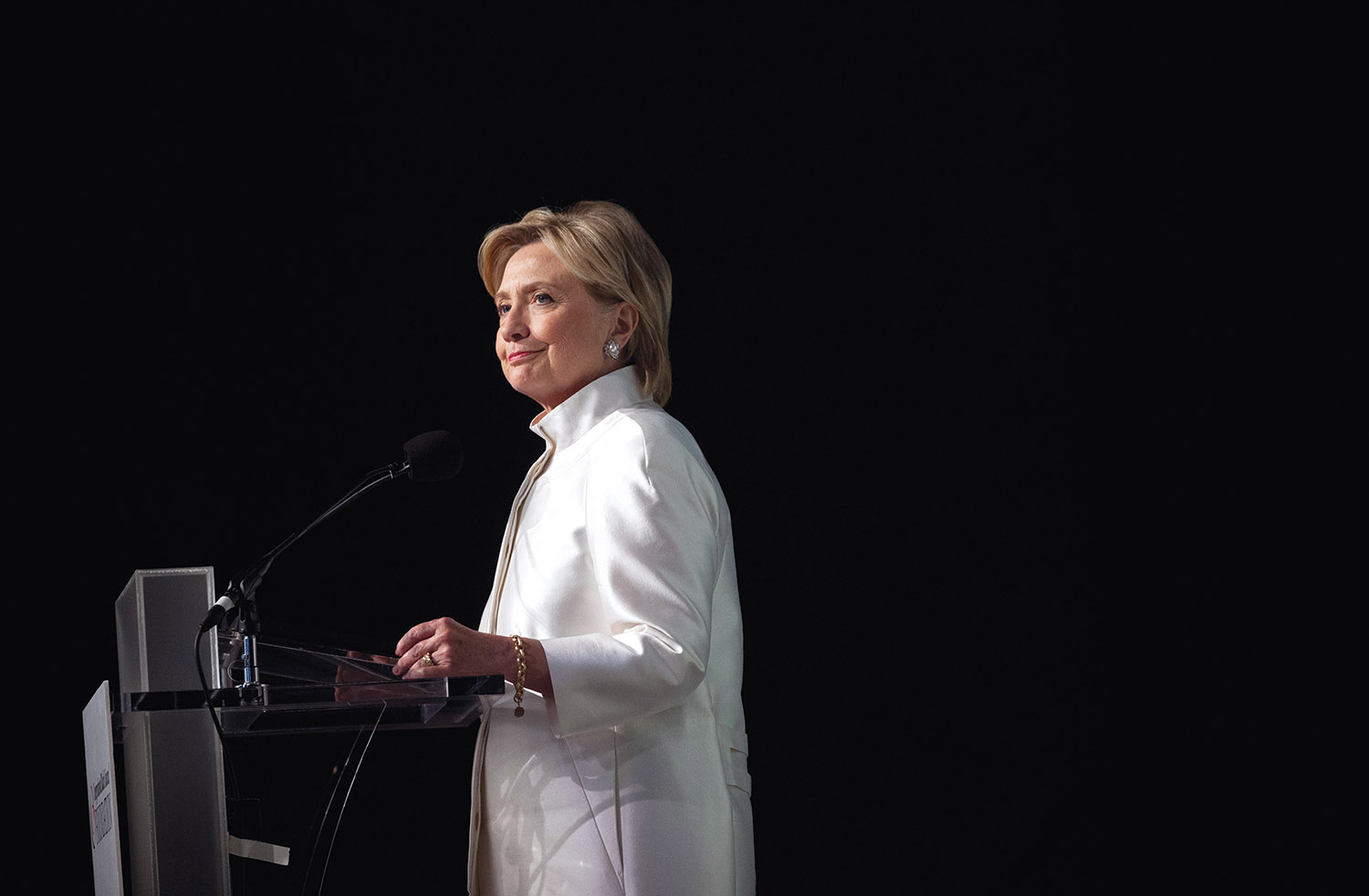

Speaking to a friendly union crowd, Hillary Clinton briefly let her frustration show. “Why aren’t I 50 points ahead, you might ask,” she said, referring to the race against Republican nominee Donald Trump.

Democrats are asking the same question. They have rallied behind their nominee, and the party’s elected officials from President Obama all the way down to local officeholders are hitting the campaign trail on her behalf. With Election Day now just weeks away, Clinton isn’t 50 points ahead. The presidential contest could go either way.

The race for control of Congress is in a similarly precarious position. Clinton could not only hold the White House for the Democrats but also deliver them from their minority status in the Senate. Or Trump, a candidate nearly all Democrats say is uniquely unqualified, could beat her and usher in the first period of unified control of the elected branches of the federal government in eight years.

“We’re a little antsy,” said a Democratic strategist surveying the state of play in the race for the presidency and the Senate.

Trump is highly competitive in battleground states. Polling suggests he’s likely to flip Ohio, Florida and Iowa into the Republican column and is gaining in Nevada, Colorado and Virginia. If he runs the table in the states won by Mitt Romney in 2012, he has several plausible paths to a narrow win in the Electoral College.

At the same time, he is underperforming in reliably red states Georgia, Arizona and even Utah and Texas. So Clinton’s dream scenario of running far ahead of the New York businessman may not be farfetched.

It all depends on whether the two split the competitive states or one candidate winds up more or less sweeping them, as happened in the recent past. George W. Bush carried all the swing states against John Kerry in 2004. Barack Obama beat Romney in all of them but North Carolina in 2012.

Based on a realistic assessment of the late September polling, Trump could easily be looking at a small electoral majority in the 270s or 280s, more than enough to be elected president. Or Clinton could regain her edge in the battlegrounds as Gary Johnson and Jill Stein voters come home and pick off a Romney state or two, potentially blowing past 320 electoral votes.

That’s how variable the presidential race is right now, which has major implications for which party will control the Senate. Yet some outcomes are likelier than others. Looking ahead to November, here are the three scenarios that are most plausible, and what each would mean for at least the first two years of that presidency.

President Clinton with a Democratic Senate

With Election Day now just weeks away, Hillary Clinton isn’t 50 points ahead. (AP Photos)

Both Clinton’s husband and Obama, the last two Democratic presidents, have benefited from supermajorities in both houses of Congress. Democrats at one point held a 57-43 edge during Bill Clinton’s first term. They briefly enjoyed a 60-vote, filibuster-proof majority under Obama. It was during this period that Obama achieved all his major legislative victories, with Republicans forcing him to resort to his phone and pen afterward.

Hillary Clinton won’t be so lucky. Her Democratic majority would certainly be smaller and she may have to fight more to get legislation passed. But there is a Supreme Court vacancy to fill with a couple more on the way. A Democratic Senate makes the confirmation process much easier.

Chuck Schumer, the man who would become majority leader in that scenario, may also be more willing than his predecessors to use the “nuclear option” to abolish or severely limit the filibuster. If so, Clinton could get her favorite bills passed after all — with one major caveat.

Tax and spending bills constitutionally must begin in the House, which can thwart any other Clinton initiatives even if they pass the Senate. House Speaker Paul Ryan is not likely to give Clinton much of what she wants.

Clinton coupled with a Democratic House and Senate can’t be completely ruled out if she surges late or does win the Electoral College landslide even her current polling suggests is possible. Given the sheer size of the Republican majority and the high re-election rate of House incumbents, it’s not terribly likely.

“House Republicans have been working hard for their districts, both at home and in Washington, and it’s clear their constituents appreciate their efforts and will reward them this fall,” said National Republican Campaign Committee spokeswoman Katie Martin. “The reality is House Democrats failed to recruit viable candidates in competitive districts across the country, and are now faced with the reality that they will continue to flounder in the minority.”

Even if Democrats won a bigger victory than looks possible, they would have to pick up seats in more conservative areas where the new members wouldn’t always be able to vote along the party line. Republicans tend to have smaller majorities that are more ideologically cohesive. Democrats have had bigger majorities but have had to deal with more division due to ideological diversity.

In 1993, Bill Clinton’s Democrats had over a dozen more Senate seats than the Republicans and over 80 more House seats. His tax increase still only passed the House by one vote and required Vice President Al Gore to break a tie in the Senate.

Sixteen years later, Obama had three-fifths Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. Obamacare still barely passed. The Waxman-Markey energy package was defeated. Comprehensive immigration reform wasn’t even tried.

Hillary Clinton would face even more daunting odds with fragile Democratic majorities. She can hope that denouncing Republican disagreement as obstructionism will help her avoid the big midterm losses that plagued Obama and her husband. A safer bet is that 2018 looks more like Republican midterm wave years 1994, 2010 and 2012 than the Democratic sweep of 2006.

Before Democrats can worry about that, however, they must at least pair Clinton with a Democratic Senate this year. The party establishment’s preferred candidates won their primaries and even if some of them are not doing well currently, they include former governors and senators. Democrats expanded their opportunities when Evan Bayh, an Indiana Democrat who was both, came out of retirement to vie for a Republican-held seat.

“This Democrat Senate candidate class is unfairly maligned,” said a Democratic consultant. “Even if you disagree, most of them are good enough to win.”

President Clinton with a Republican Congress

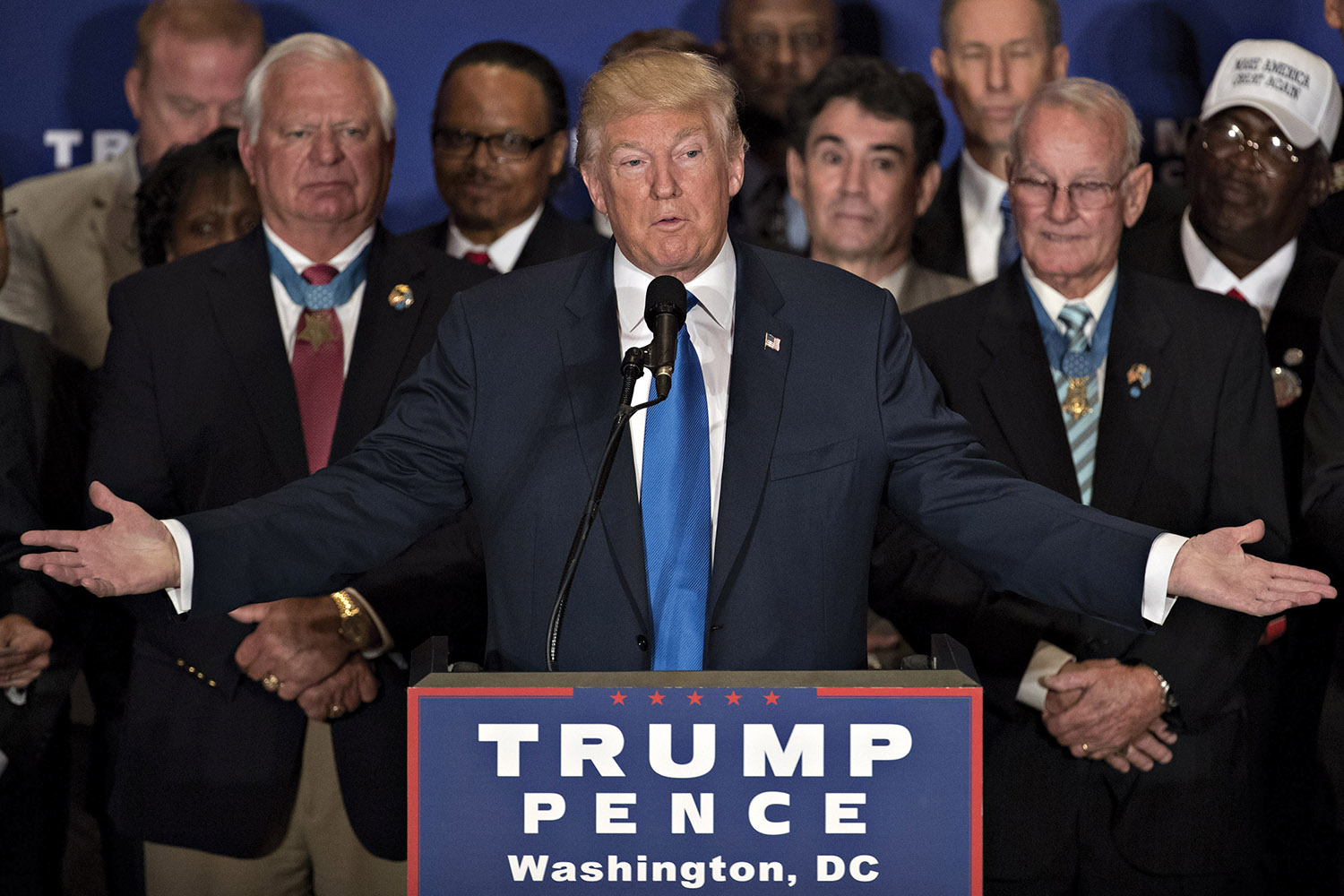

The race for control of Congress is in a precarious position: A Clinton win could deliver Democrats from their minority status in the Senate. Or Trump could beat her and usher in the first period of unified control.

Embattled Republican incumbents are starting to rebound in their re-election races. That’s not good news for the Democrats’ hopes of retaking the Senate.

“I think Republicans have a very good chance at keeping the Senate. If you asked me that a month ago, I would have said the Democrats have a significant lead and edge on retaking it, but things are tightening,” GOP consultant Ron Bonjean told the Washington Examiner. “The races are tighter in the battleground states.”

Rob Portman was thought to be in for a tough race in Ohio against Democratic former Gov. Ted Strickland. Instead, the Republican is up by 13.5 percentage points, according to the latest RealClearPolitics state-level polling average.

Democrats hoped this would be the year John McCain was finally vulnerable. As Trump’s Arizona numbers weakened, Democrats expected higher Hispanic voter turnout as the top of the ticket dragged McCain down with him. But the longtime senator is hanging on, leading Democrat Ann Kirkpatrick by 13.7 points.

Part of this is due to Trump recovering in the polls. Even trimming Clinton’s Pennsylvania lead a bit makes life easier for GOP Sen. Pat Toomey, who is up by 1 point in the latest Quinnipiac poll and has cut his Democratic challenger’s advantage in the RealClearPolitics average to just 0.2 points.

A lot of it is Republicans outperforming Trump, in some cases by margins that are much better than anyone could have expected. A Monmouth University poll in New Hampshire showed Clinton beating Trump by 9 points, but Republican Sen. Kelly Ayotte clinging to a 2-point lead against Democratic challenger Maggie Hassan, the sitting governor.

In Florida, the Senate race has turned on two key developments. Republican incumbent Marco Rubio reversed his decision to retire and has consistently led in the polls since doing so. Democratic challenger Patrick Murphy has faced questions about embellishing his resume and has generally been a less effective candidate than expected.

Congressional Republicans would likely try to identify popular conservative bills that President Clinton would veto. They tried that with her husband in the 1990s with mixed success, eventually getting welfare reform and tax cuts. They have not proved as capable of doing this under Obama due to internal divisions.

If Clinton faces an all-Republican Congress, she will have a difficult time getting judges confirmed or legislation passed. The one exception may be on trade, if she reverses course on policies such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership once in office — a real irony given the strong protectionist pushes by Trump and Bernie Sanders that have dominated 2016.

One upside for Clinton is that the strategy of running against the GOP in the 2018 midterms would have a slightly greater chance of succeeding, even with Democrats having to defend more seats than in the 2016 cycle.

President Trump and a Republican Congress

The Republican congressional leadership in Washington may not like Donald Trump, but they now need him to do well.

The Republican congressional leadership in Washington may not like Trump. They certainly did not want him to be the nominee. But they now need him to do well.

When Trump was in the doldrums after the Democratic convention, there was talk of national Republicans cutting off his funding and instead pouring the money into salvaging their congressional majorities as they did during the 1996 campaign in which Sen. Bob Dole was such a doleful candidate.

“We did advertising and a lot of message delivery about not giving [Bill] Clinton a blank check,” a Republican official told the Washington Examiner. “I think that would be premature now, but at some point it might be absolutely appropriate to say that.”

No more. Trump doing well, even if not winning outright, is vital to preserving those majorities. This has particularly forced a shotgun wedding with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who is no Trump fan. The same battleground states Trump needs to win the White House — Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Nevada, Wisconsin — feature the Senate races that will determine whether McConnell remains majority leader or is demoted to minority leader.

As long as Trump doesn’t lose any red states, his margin of victory won’t affect his electoral vote haul. It doesn’t matter for Trump whether he wins Utah by 50 points or 5 points, he’ll still take all its electoral votes. But it may matter a great deal to Mia Love, the Republican incumbent representing the only Utah congressional district Democrats have any chance of winning in November.

When Trump was trailing badly in August, Rob Portman of Ohio and Marco Rubio of Florida appeared to be the only endangered incumbent GOP senators who would survive. As Trump has rebounded, however, Mark Kirk of Illinois and Ron Johnson of Wisconsin are the only ones who aren’t at least even with their Democratic challengers.

How well would Trump and a Republican Congress work together? This is the biggest wildcard of them all. Nobody really knows what Trump’s priorities or governing style would be. He is much more protectionist on trade than congressional Republicans, a stance he is unlikely to revisit as it is one of his few consistent policy positions dating back to the Reagan administration, and pushes a harder line on immigration than the party’s donors or consultants think wise.

On foreign policy, Republicans have sometimes taken the lead in slamming Trump as too close to Russia. He opposed the Iraq War, at least by 2004. Only seven Republican members of Congress voted against it, and they are all gone from Capitol Hill.

Ryan has entertained high hopes that a President Trump would sign a slew of conservative bills that Clinton would surely veto. Corporate tax reform and tax cuts seem promising areas of agreement. But Ryan has also frequently rebuked Trump, even after reluctantly endorsing him, and tried to present a different vision of conservatism than espoused by the party’s standard-bearer.

Some Republicans fear that a Trump administration would endanger the party’s majorities all over again in 2018. “I don’t even want to think about it,” said a GOP consultant.

Will Trump, a frequent donor to New York Democrats including Schumer, try to be more of a deal-maker than a Republican regular? Will he try to remake the GOP in his nationalist and populist image, working with Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions and House backbenchers more than the leadership? Will he frequently resort to executive orders?

It’s a sign of how uncertain things are in 2016 that Republicans will face questions about their party’s future even if they win it all.