Last week, Monmouth University published a poll showing Republican Ed Gillespie ahead of Democrat Ralph Northam by one point in the race for Virginia’s governorship. This poll shocked some political observers—some had likely looked at Virginia’s recent results on the presidential level and President Trump’s low approval rating and concluded that Northam had this race locked up. And while the polling since the Monmouth poll has been mixed (One poll had Northam up by 14, another had him up by seven and a third put Gillespie up by eight), the average shows Northam up by only four points.

These new polls have left some election watchers wondering why the race is this close. So before the last week of the campaign, it’s worth zooming out and trying to explain the state of the race. There are individual factors that matter in Virginia — partisanship, demographics, the difference between gubernatorial and congressional elections and the campaign–worth pulling apart to try to figure out why the race is as close as it is.

Virginia Is Only a Light Blue State

If you’ve been following Virginia politics for the last few electoral cycles, you probably noticed some significant shifts. After a long streak of Republican wins on the presidential level, the state voted for Barack Obama twice and Hillary Clinton once. And Democrats also now hold both of the state’s Senate seats and the governor’s mansion.

But it’s not a safely blue state.

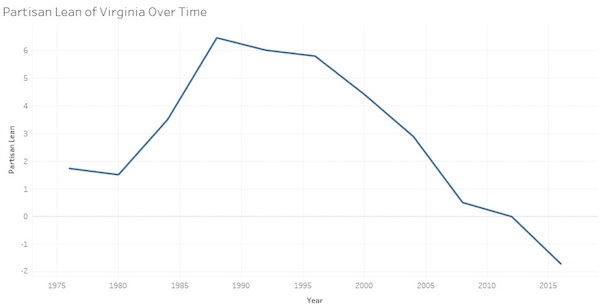

This graphic shows the trend in Virginia’s state-level partisan lean—that is, how much Virginia leaned right or left in a given presidential election compared to the nation as a whole. Specifically, I subtracted the two-party national presidential vote (which excludes all parties except for the Democrats and the Republicans) from the two-party presidential vote in Virginia. A higher partisan lean means that Virginia voted more Republican than the country as a whole (i.e. the GOP’s share of the two-party vote was higher in Virginia than the United States), and values below zero indicate a Democratic lean.

The long-term political trends in the Virginia are complicated (the South’s historical transition from Democratic to Republican deserves at least its own series of pieces), but the trend over the past few decades is clear. Virginia, despite being a safely Republican state for much of the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, has been steadily moving leftward for about three decades. There’s more than one reason for this trend, but the growth of Northern Virginia (suburbs and exurbs of Washington D.C.) and increasing Democratic strength in large metro areas explains a lot.

But Virginia’s trend hasn’t turned it into a fully blue state yet. In 2008, Obama won the state by six points while winning nationally by seven. His 2012 margin in the state was almost identical to his national popular vote margin. And in 2016, Hillary Clinton performed better in Virginia than she did nationally, but only by about three points.

In other words, Virginia has moved a lot since the 1980s, but it hasn’t moved so far left that a Republican would be unable to win the state. Moreover, if young voters and racial minorities compose a smaller amount of the off-year electorate than they do in a general election (Geoff Skelley has a great piece that zooms in on this and the campaign to explain the closeness of the race), then the baseline makeup of the state could be pushed closer to the political center.

Trump Matters. But How Much?

The historical trends in Virginia are obviously important, but they leave out a key part of the story of 2017—the Trump Effect.

President Trump isn’t popular. Both national surveys and Virginia polls show that his job approval rating is far underwater (RCP puts his approval rating at 39.1 percent and Morning Consult put it at 42 percent in Virginia in September). And his unpopularity is probably part of the reason Republicans are suffering in House generic polls and underperforming or losing in special elections.

But the Virginia gubernatorial election, to some degree, may have uncoupled itself from national politics. According to a Monmouth poll, only 29 percent of respondents say Donald Trump is a major factor in deciding how they’ll vote for governor. And a Washington Post poll shows that 54 percent of registered voters in Virginia say that Trump is not a factor in their choice for governor.

And while it’s not always advisable to take everything voters say at face value (e.g. many Americans who claim to be independent vote like partisans), there’s strong evidence that gubernatorial elections in general aren’t tied to national conditions in the same way that congressional elections are. In 2016, the relationship between a state’s presidential vote and its choice for governor wasn’t very strong. And while state-level partisanship had some predictive power in gubernatorial results in 2010, it had virtually none in 2006.

In other words, the polls might be close because a gubernatorial election in a somewhat swing-y state allows Gillespie and Northam themselves to have greater sway over the race. Gillespie has been trying to blend his traditional, establishment-friendly appeal with some decidedly Trumpian messages and tactics, and for most of the campaign Northam has attempted to cast himself as a decent person with traditionally left-of-center politics. And so far, those strategies have created a relatively close race.

It’s worth noting that Northam still has the edge here. The average of recent polls puts him ahead, and while the national political environment doesn’t control this race, it’s not worth nothing.

That being said, this race isn’t over. Last minute events, changes in strategy or just undecided voters deciding on their pick could push the polls in either direction before Election Day. And polls, while very useful, aren’t infallible. So it’s worth continuing to watch this race closely, realizing that Northam at this moment has the advantage.