Sweeping off the Atlantic in August 1873, a killer storm decimated the town of Gloucester, Massachusetts. One hundred and thirty-four men perished, nine fishing vessels were lost, and 90% of the fishing industry was destroyed. Wives wept for their husbands lost at sea. Children cried for their fathers. A news reporter proclaimed that the “history of Gloucester fishing has been written in tears.”

The iconic 19th-century artist Winslow Homer (1836-1910), who was invited to create a memorial, painted the tragedy in a lower key. He focuses on a boy sitting on a dory staring into the ocean. Homer created three versions of the image, titling the first one, “Waiting for Dad.” In the next two, he added a woman holding a baby.

Each version captures the calm after the storm and, through layers of ambiguity, invites viewers to decipher the narrative conveyed by the picture. According to the curator and arts consultant William Cross, “the geometry [of the painting] leads us unconsciously to absorb the unsettling possibility of a tragic outcome” and indicates the power of this image that would become one of Homer’s most celebrated works of art.

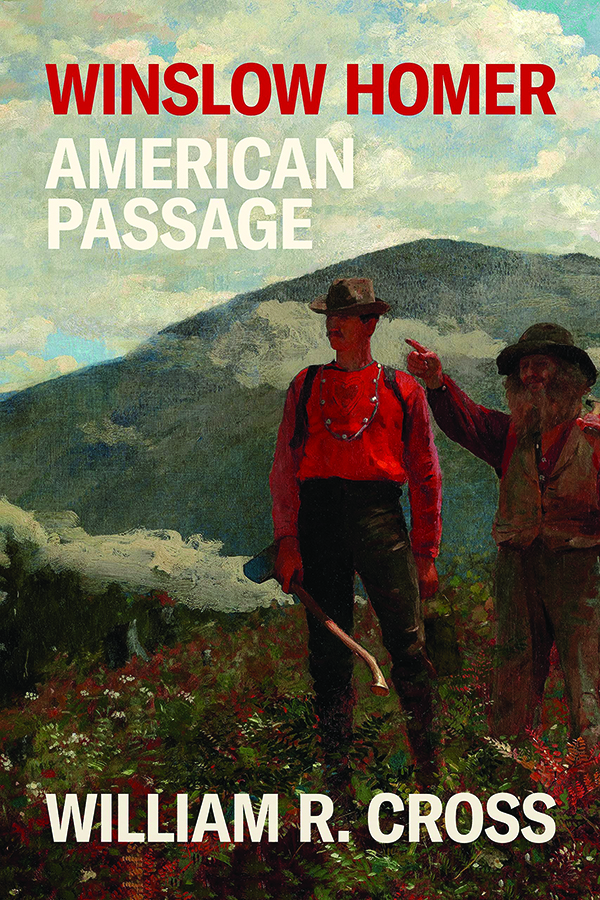

In Winslow Homer: American Passage, Cross argues that Homer was one of America’s most independent-minded artists. He owed almost nothing to art fads. He told his own truth, “seen in his way and expressed in his way,” not that of newspaper headlines or other artists. After finishing his apprenticeship, Homer insisted he would call no man “master.” He never did. When he was mature, he advised younger artists not to study books or paintings but to learn from nature.

Cross covers the trajectory of Homer’s career. He moves chronologically from Homer’s childhood in Cambridge to his years in New York as a freelance artist for several publications, including Harper’s. He gets to his time on assignment at the Virginia front capturing scenes from the Civil War and his trips to the Adirondack mountains, Quebec, Cuba, the Bahamas, Europe, Cullercoats in England, and to his final years at Prouts Neck, Maine, where Homer zealously tried to depict the dynamic force of the ocean.

Mostly self-taught, Homer was the middle son of an artist mother who specialized in watercolors and of a domineering father whose outspokenness often embarrassed Winslow and inclined him to keep his opinions to himself. He began drawing and painting in watercolor under his mother’s tutelage. Cross includes several of Homer’s earliest drawings. His father hoped that his three sons would study at Harvard. Homer’s older brother, Charles, did graduate from Harvard and received high honors. But Homer, like his younger brother Arthur, did not finish high school.

Instead, Homer secured a three-and-a-half-year apprenticeship at the prominent Bufford’s Lithography shop in Boston, where he showed an early talent for drawing. Here in the shop in 1854, Cross speculates, Homer would have seen the arrest of Anthony Burns, an escaped slave working as an assistant at a nearby clothing store. Cross argues this incident aroused Homer’s sympathy for the plight of former slaves.

Years later, as a professional artist, he would create numerous empathetic portrayals of black people during and after the Civil War in the North and the South as well as those who lived in the Bahamas and Cuba. Some of these paintings drew negative reviews from critics. Homer persisted.

One of his most expressive paintings, “Near Andersonville,” shows a young black woman standing in her doorway while in the distance captured Union soldiers are led to Andersonville prison. Another favorite is “The Gulf Stream,” which shows a black man in a small boat barely staying afloat amid sharks swimming in an angry sea. As Cross points out, both images suggest the narrative quality inherent in Homer’s work.

Since Homer was a private man and destroyed most of his correspondence, Cross gleaned information from newspapers, historical documents, and previous biographers for his book. As an avid reader, Cross suggests, Homer would have been exposed to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s philosophy of self-reliance, which was widespread in New England. He was also probably aware of Henry David Thoreau’s views on nature. Homer, too, went to the wilderness to live (and paint) deliberately.

Cross makes several references to Emily Dickinson, quoting her poem “Tell all the truth but tell it slant … ” and implying that it is integral to Homer’s way of making art. Cross also cites Dickinson’s poem “The Soul Selects Her Own Society” to convey Homer’s tendency to keep to himself. Homer had a door knocker shaped like the head of Medusa (replete with snakes) to ward off visitors. Although the Dickinson references are engaging, they exemplify Cross’s tendency to provide a few too many extraneous specifics that would be better placed in his endnotes.

It’s possible, Cross says, but not probable that Homer had an unrequited love affair with another artist, Helena de Kay, as several scholars believe. Cross thinks it was more likely that Homer was in love with Eugenia Renne, a teacher featured in his paintings. Cross even includes an unsigned poem, which he believes Homer wrote to accompany a painting.

Cross’s expertise shines when he focuses on Homer, the artist who was able to see and include the small details that reinforced the storyline inherent in a scene. His discussion of “Mending the Nets,” one of Homer’s most admired watercolors, for example, shows the fishwives of Cullercoats, Northumberland, in England as they mend their husbands’ nets on the beach beside the North Sea.

Homer, as Cross points out, used darker colors for the picture, signifying “a funereal tone, as if the women are weaving shrouds for the dead.” Cross notes the women’s shapes and resemblance to sculptures from the Parthenon in the British Museum. He also describes Homer’s careful geometric proportions as well as his reworking of the painting.

Lloyd Goodrich, one of Homer’s first biographers, called him “the greatest pictorial poet of outdoor life in nineteenth century America.” One summer, Homer executed 100 watercolors on Ten Pound Island (near Gloucester, Massachusetts), including a series of sunsets one critic described as a “demonic splendor of stormy sunset skies and waters.” Another critic called Homer’s paintings “genuinely ebullient … expressions of awestruck gratitude in the face of such beauty.”

Or, as Homer put it succinctly in a letter to his father, “The Sun will not rise, or set, without my notice, and thanks.” That gratitude, as Cross suggests in this perceptive biography, is the secret to Homer’s preeminence as an artist — then and now.

Diane Scharper has written or edited seven books. She teaches memoir and poetry for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.