My father, Glen “Wheels” Wheless, is part of a group of retired naval aviators and service members who have spent the last three years designing, obtaining funding for, and seeking approvals to install a monument to the F-14 Tomcat at the Virginia Beach oceanfront. The four-paneled Tomcat Monument bears laser-etched images of the jet that gained many admirers as its distinctive swing-wing silhouette roared over the country between its first test run in 1970 and its final flight in 2006. An “In Memoriam” panel is also inscribed with the names and call signs of the 68 aviators who perished while operating the beloved F-14.

I had been looking forward to the Tomcat Monument’s May 13 dedication to pay my respects to one of the aviators, John “Yogi” Graham, whose name is etched on its side. Unfortunately, the coronavirus pandemic has both delayed the monument’s unveiling, which is now tentatively scheduled for late September, and stunted the influx of Memorial Day visitors to the area. For the benefit of those who might have passed the monument and reflected on the aviators who lost their lives in service to their country today, I share my own story about Yogi.

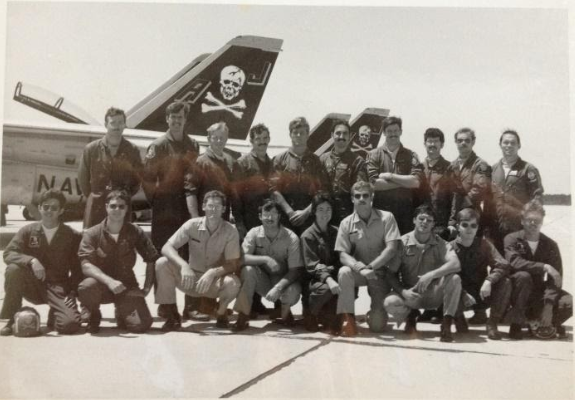

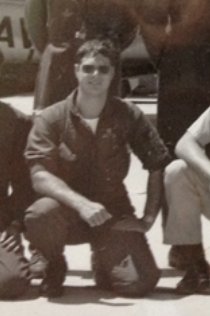

Although I grew up on tales of flying the Tomcat, I first heard my father talk about Yogi several years ago as we ate dinner with some of our dearest friends.

“You remember ‘Walking on the Moon’? The Police?” my father asked the table. We all nodded. My dad explained that Yogi, one of the radar intercept officers in his training class at Naval Air Station Pensacola, had loved the song. Yogi was known to belt the tune out as he danced wildly around at various bars while training in Key West.

After training, my father explained, he and Yogi went on to separate squadrons. Yogi was serving on the USS Nimitz when a normal takeoff from the carrier deck took a dramatic turn.

As his Tomcat was accelerated from zero to 130 knots during the catapult stroke, the jet’s starboard engine failed. Recognizing there was not enough speed to become airborne, Yogi’s pilot, the well-respected John “Jack” Watson Jr., instinctively pulled back on the stick.

My dad explained how the maneuver was sound in the F-4, the jet that Jack cut his teeth flying. But “no one had any idea how to handle that situation with an F-14,” he continued. The Tomcat’s engines were set further apart, so the loss of an engine at slow speed meant pulling back on the stick would send the jet into a roll at a perilous altitude. Yogi and Jack ejected before their jet hit the ocean.

As the Navy assessed the mishap and communicated new emergency procedures, video from Yogi’s failed takeoff was sent to each F-14 squadron. On the USS Kennedy, my father’s squadron mates assembled in the ready room. “We watched Yogi’s jet go right off the deck,” my father said. “And then there was this flutter of white.” They were looking at Yogi’s kneeboard cards. “That’s all you saw: just white stuff flying through the air.”

As my dad told this story at the dinner table, each of us were silent. We all hoped to hear that Yogi and Jack had survived. Instead, we learned that both men had perished on ejecting into the water. “It was completely unsurvivable,” my dad told us.

He shook his head. “Yogi…loved that song.”

Several weeks later, I asked my father about Yogi again as we spoke over the phone. He told me the story once more before pausing. “I would have said this the other night, but we got distracted,” he said. I felt as though time were suspended while my father explained how Yogi’s and Jack’s deaths saved his life.

“You know, if those guys hadn’t died, it would have been me.”

The Navy determined that, if the F-14 lost an engine while in afterburner during a catapult launch, it was critical to keep the nose of the aircraft from rotating upward. Days after the new procedure was disseminated through the ranks of Tomcat radar intercept officers and pilots, my father and his skipper, Jack “Quail” Dantone, were being shot off the deck of the USS Kennedy when their Tomcat lost an engine with afterburners engaged.

“All these lights and warning alarms started going off,” my dad said, as he and Quail, a former F-4 pilot, began to accelerate down the catapult track. Over the radio, my dad heard Air Boss warn, “Burner blowout Cat One!”

“Keep your nose down, keep your nose down,” my dad recalled telling Quail. Quail kept the jet’s nose low and never pulled back on the stick. He told my father not to eject. “I had my hand on the lower ejection handle the whole time,” my dad told me. “I always did during a [catapult] shot, just in case.”

“We just kept going,” my father continued as I held my breath. After coming off the ship, “We shot left because only the right engine was running, and then we settled like a rock.” Quail and Wheels would only discover how close to death they had come after they landed. They watched the video of their takeoff in the ready room. “We had dropped so low after that launch that you couldn’t even see the…jet. It was below the flight deck.”

In the years since my father told me about Yogi, I have often contemplated his accident and found myself overcome with gratitude for the sacrifice made by a man I never knew. I always loved the escapist “Walking on the Moon,” but my appreciation for the seemingly portentous song has grown since learning how deeply Yogi loved it. I listen to the tune often now. When I do, I always think of Yogi, swaying along in a sweaty Key West bar.

Yogi and Jack did not perish while dropping bombs over a deadly enemy. They were not engaged in a daring dogfight with an enemy MiG. But their deaths are no less meaningful because they occurred during training. Because of Yogi and Jack, the Navy was able to discover and craft a procedure for a potential emergency situation in the F-14 that would increase U.S. preparedness during wartime operations. Because of Yogi and Jack, other men would live. I am especially grateful because one of those men is my father.

This Memorial Day, I will not be able to visit the Tomcat Monument in Virginia Beach to pay my respects to a man whose sacrifice gave me so many important decades with my father, who taught me about the exceptional nature of the country where I reside, who emphasized the importance of service, and who continues to show me how to live well. But rest assured that when the Tomcat Monument is unveiled, I will touch Yogi’s name, drink a hearty toast to his memory, and perhaps even dance along to “Walking on the Moon” in his honor. In the meantime, I will spend this holiday thinking of Yogi and Jack and the rest of the men and women who have given their lives to ensure not just my freedom, but the continuation of this country where I am so richly blessed to live.

Beth Bailey (@BWBailey85) is a freelance writer from the Detroit area.