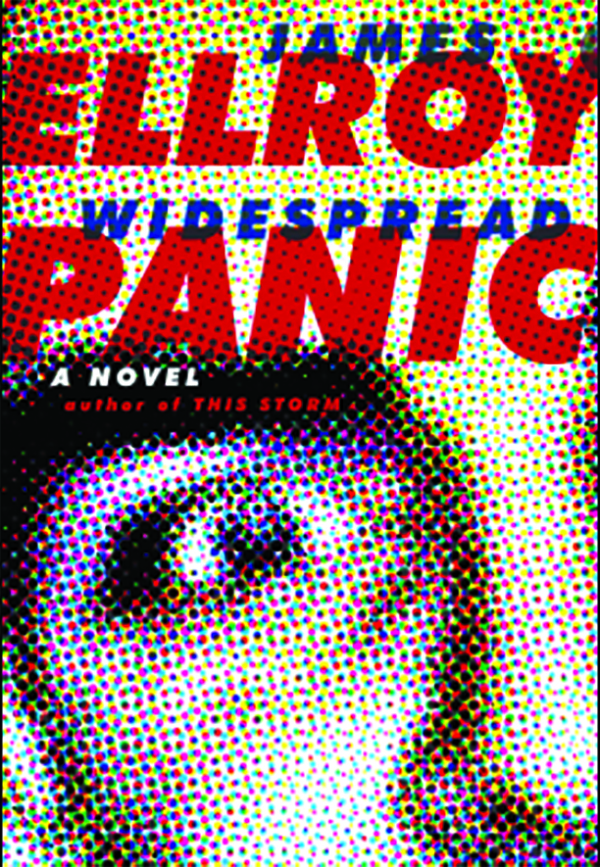

James Ellroy writes like he thinks in ALL CAPS. Occasionally, he writes in ALL CAPS, too. He rages in italics, flings exclamation points like sticks of dynamite. Though he uses more alliteration than the Gawain poet, his debt is not to the Anglo-Saxon word hoard but to the neon nastiness of the tabloid headline and the violence of comic book onomatopoeia. His energy flirts with insanity and then takes it brutally to bed. No, Mr. Ellroy doesn’t do subtlety. Reading Widespread Panic, his latest outing and the third book of his Second L.A. Quartet series, is like getting hit in the mouth with a sap over and over again and then saying, through broken and bloody teeth, “This is awesome.”

A little too rare is the author of literary fiction willing to risk his readers’ displeasure on a truly vile narrator. The creepo protagonist is a staple of crime fiction, though, and it’s a specialty of Ellroy’s. Even his hero police, such as Bud White in L.A. Confidential, twist arms, crack skulls, plant drop guns, and force confessions. Freddy Otash, the ostensible hero of Widespread Panic, is fouler yet: ultraviolent, machinating, opportunistic, greedy. He’s a former “Hollyweird” officer, a private investigator whose moral compass blows where it lists, a fixer, a bagman, a pimp, and a night-stalking blackmail-happy paparazzo who invades privacy for fun and profit. He’s so bad, in fact, that when we first make his acquaintance, he’s speaking to us from Purgatory.

That’s literal Purgatory, where “you’re stuck with the body you had on Earth when you died” and “eat nothing but coach-class airplane food.” Neither booze nor broads are anywhere to be found. Again, no subtlety here: “My cunning keepers are currently dangling a deal: Record your jaundiced journey. Trumpet the truth, triumphant. Hope to Heaven, and hit that high note. Baby, it’s time to CONFESS.” For Freddy, this soul-cleansing penance entails reliving his misdeeds in lurid Technicolor. The man who engorged his bankroll interfering with the lives of others must bear his sinful breast at last.

Fred Otash (1922-1992) was, as is the case with many of Ellroy’s characters, a real man, not to mention the model for Chinatown’s Jake Gittes. A Lebanese American Marine Corps veteran of World War II, Otash tumbled hard from respectability. He fed information to the tabloid Confidential in the 1950s. He bugged Marilyn Monroe’s home to get to the Kennedy brothers, and he claimed to have listened to her in the throes of both passion and death. He does a lot worse in Widespread Panic. (How easily one forgets that during the sunny, smiling ‘50s of popular imagination, much of the adult male population was conversant by necessity with extreme violence and horror. Old habits die hard.)

Freddy may be in Purgatory, but ‘50s Los Angeles seems in Ellroy’s maximalist telling like a Boschian hell on earth. It is just as the decade begins that Freddy, still a police officer, commits the sin that will shape the rest of his life: executing a cop killer, on sub rosa departmental orders. The wrinkle? The cop survives, meaning Freddy has upset what passes, to his warped conscience, for the scales of justice. He sends money to his victim’s widow, Joan Horvath — anonymously, of course. When Joan is murdered, Freddy switches into masked-vigilante mode, calling in favors and calling down fire and brimstone.

“My city,” he boasts, “teems with tattle tipsters on my payroll. Hotel rooms are hot-sheet hives hooked up to my headset.” He counts “Jimmy,” a young James Dean, among his employers. At one point, they swill Old Crow while eavesdropping on an embarrassing encounter between Jack Kennedy and Ingrid Bergman. Freddy does a little fixing for the senator, too. He arranges a beard for Rock Hudson. He shakes down Gary Cooper in exchange for killing a story about an underage girl. Here and there we see Freddy’s softer side, as when he catsits Liberace’s leopard or woos a succession of “boss-built and credibly-credentialed” women. And then, next thing you know, he’s back at it, melting a man’s hand off in fryer oil or blowing up an FBI listening post.

Freddy’s Dexedrine-driven dirty work leads to an investigation of several members of a communist cell, including an assassin — and Freddy manages to fall for her, too. The serial rapist Caryl Chessman appears on Freddy’s radar. The plot achieves such an intimidating intricacy, not to mention self-referentiality, that the weary reader is tempted to make a list of names to look up and keep handy. This would have, after all, the added benefit of helping sort out which of these people actually existed and how unfair Ellroy has been to them. The hitch is that such a list would look like the closing credits of a sword-and-sandals epic. So read attentively, and good luck.

Speaking of “lists of names,” Freddy’s rabid posture toward communism is a hilarious departure from what we’re accustomed to seeing in high-status cultural productions. “I’ll work for anyone but the Reds,” he thunders. The beauty of this hollow moralizing, from a scumbag who has violated every law of God and man, is that it can be read as either a satire or a celebration of preferring your own kind of corruption to the imported variety.

The book provokes a lot of uneasy thoughts about privacy and its enemies — surveillance, tabloid journalism, police brutality, “Commo” repression, and (sorry, folks) eternal judgment. It ably sends up the way we live now, still trapped in a pas de deux of exhibitionism and voyeurism, still obsessed with airing dirty laundry, with denunciation, with personal destruction. As if anyone could miss it, Ellroy goes ahead and spells it right out: “Confidential presaged the infantile Internet. … We voyeur-vamped America and got her hooked on the shivering shit. WE CREATED TODAY’S TELL-ALL MEDIA CULTURE.”

Widespread Panic has the virtue of feeling fantastic and utterly authentic at the same time: fantastic because of its hellishly overheated prose and its guilt-wracked, helpless prurience, authentic because of its immersive atmospherics and cranked-up dialogue. It also feels wise, as Ellroy understands that wickedness exists and it exists in all of us. No, he doesn’t do subtlety. But it counts as subtlety, in an era of asinine superhero blockbusters, to recognize that there are no good guys and bad guys, only bad guys and really, really bad guys. It was true in the ‘50s, and it will still be true when the last light goes out in Los Angeles. But fear not, Ellroy says. Confession is good for the soul.

Stefan Beck is a writer living in Hudson, New York.