On November 7, Democratic lieutenant governor Ralph Northam became the governor-elect of Virginia, beating Republican Ed Gillespie by a nine point margin. Two days later, the political world shifted almost all its focus to Alabama. Various news outlets have now reported that while Republican candidate Roy Moore was in his 30s, he pursued teenage girls, allegedly sexually assaulting a 14-year-old and a 16 year old. Since then his standing in the polls has dropped, and almost the entire political world has (rightly) focused on that race.

If you’re not following the Alabama race, you should be. We’ve written on it extensively and will continue to do so. But I want to discuss Virginia a little bit more before the conventional wisdom on this race congeals. Specifically, I want to try to figure out how much of Northam’s victory can be attributed to static factors like Virginia’s partisan lean and demographics, and how much is due to dynamic factors like the national political environment and campaign strategy.

This question matters: If Virginia is now simply a blue state no Republican can ever win, Republicans might feel a bit less panicked about their chances in the wider 2018 midterm elections. And if Democrats misunderstand why they won in Virginia, they make incorrect choices about how to allocate resources next year.

There’s more than one way to attack this question, but I’ll start by describing where Virginia is politically and then detail what that means for 2017 and beyond.

Virginia Is Light Blue—That Alone Didn’t Guarantee a Northam Win

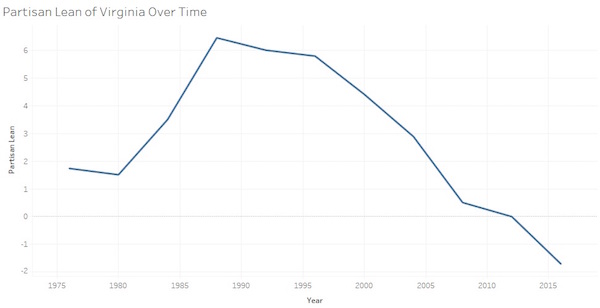

Virginia has two Democratic senators, a Democratic governor and has voted for the Democratic presidential candidate in the last three elections. But it’s not a fully blue state. To see why, first look at the state’s partisan lean. I’ve used this graphic before, but it does a good job of correcting a problematic piece of conventional wisdom.

It shows the trend in Virginia’s partisan lean—its vote in presidential elections compared to the national popular vote—with positive values indicating that the state leaned toward Republicans and negative values indicating a Democratic lean. The picture is clear—the Old Dominion was quite red in the 1980s but, it has steadily drifted left since then. In 2008 and 2012 its partisanship was close to even and in 2016 it leaned toward the Democrats by about 3 points.

The trend in Virginia is real, but its position isn’t so different from a state like Florida. The Sunshine State leaned 3 points toward the Republicans in 2016 (Trump won it by 1 percentage point while Clinton won the popular vote by 2)

And when a state leans only a few points toward one party, the other party typically isn’t shut out of statewide office. They just need the right conditions to win.

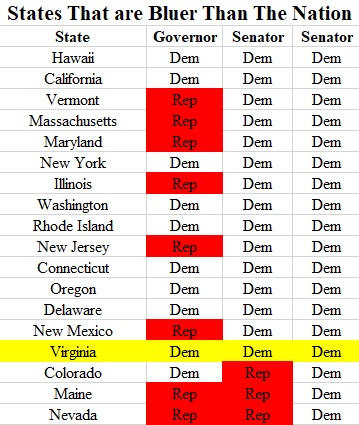

This table shows the party affiliation of governors and senators from every state where Clinton’s share of the two-party share exceeded her share of the two-party national vote (two-party just means that third parties are excluded from these calculations).

Colorado, Maine, and Nevada have all recently elected Republican senators. And New Mexico, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Vermont all currently have Republican governors (though Democrat Phil Murphy is the governor-elect of New Jersey). Some of these politicians were aided by the Republican wave of 2014* and others have built strong personal brands (e.g. Maine senator Susan Collins and Massachusetts governor Charlie Baker). But the point is that it’s not impossible for the right combination of conditions to elect a Republican in a state that’s as blue or bluer than Virginia.

In fact, it almost happened just a few years ago. Part of the reason many overrated Gillespie’s chances of scoring an upset in 2017 was that Democratic senator Mark Warner beat him by less than a percentage point in 2014. Moreover, it’s possible to imagine a universe where Hillary Clinton won the 2016 presidential election by a narrow margin, had a low approval rating in November 2017 and allowed Gillespie win by uniting the Trump and Romney wings of the GOP (note that my calculations on this match Patrick Ruffini’s here).

The point here is not to argue that Republicans should be bullish about their chances in Virginia. They shouldn’t be. But the point is that while Virginia is a light blue state and may continue to drive leftward. The point is to show that Virginia’s state-level partisanship alone wasn’t enough to give Northam that 9-point victory.

So Why Did Northam Win in 2017?

So if Ralph Northam wasn’t destined to win in Virginia, why did he win? There are a few reasonable explanations.

Donald Trump seems to be one reason. Gubernatorial races aren’t as reliably tied to presidential politics as House and Senate elections, and the polling heading into this race (a real but not overwhelming Northam lead) made it look like this race might also do its own thing. But when the results finally rolled in, the battle lines in 2017 bore a striking resemblance to those of 2016. The correlation between county-level results in 2016 and 2017 was very tight, and a simple look at the maps shows that Northam and Clinton overall had similar geographic bases of support.

Trump’s unpopularity in the suburbs was also striking.

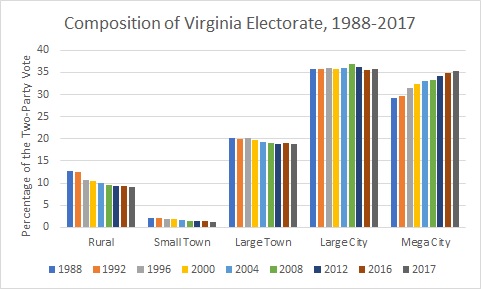

This graphic shows the percent of the electorate in rural areas, small towns, large towns, large cities and mega cities (Sean Trende and I defined these terms and generated similar graphics here) in Virginia in presidential elections from 1988 to 2016 as well as the gubernatorial election of 2017.

This graphic suggests Trump’s unpopularity mattered. Rural areas and small towns where Trump (and Gillespie) often performed well were a smaller part of the electorate in 2017, while large urban made up a larger part of the two-party vote. In other words, Trump enthusiasts in rural parts of the state may have stayed home while college-educated Democrats in suburban areas continued to turn out. While population growth in Northern Virginia explains much of the movement in this graph between 1988 and 2016, it’s tougher to argue that population growth alone would shift the electorate this much in the space between the 2016 and 2017 election.

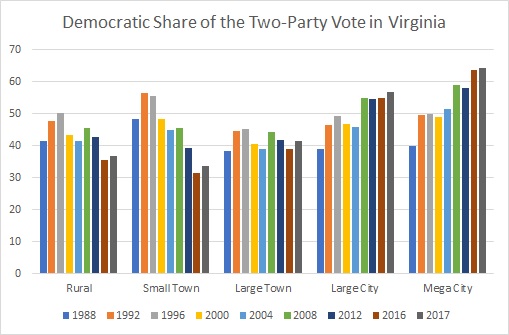

The story doesn’t change much when you look at vote shares.

Northam outperformed Clinton in every subdivision in this graphic. That’s consistent with the idea of a strong suburban performance coupled with lower-than-expected turnout among Trump voters.

The other way to tell this story is through Ed Gillespie. Gillespie’s margins in rural parts of Southwestern Virginia weren’t that far off Trump’s. But he was unable to grab some of the suburban voters who cast their ballots for him in 2014 and Mitt Romney in 2012. In other words, Gillespie tried to use the freedom afforded by a gubernatorial election to draw a new map and unite the GOP. But national conditions were too much, and he ultimately failed.

Other factors also probably played a role here. Outgoing Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe had a positive net approval rating heading into the election. Democrats were also well-organized (as demonstrated by their success down-ballot). But these factors are more tied to the particularity of the year, the dynamics of the Trump Era, the candidates themselves than they are to the makeup of the state.

So What’s It All Mean?

The bottom line here is that Northam’s win in Northern Virginia wasn’t simply due to the state being too blue for a Republican to win. Virginia may become that blue—just look at the trends in the graphics above. If those trends continue (note that it’s hard to predict how political coalitions and demographics will evolve), then Virginia could become so blue that it’s impractical for Republicans to win there absent a very favorable national environment or a truly excellent candidate.

Moreover, just because a Republican could have won in 2014 (or in some alternate universe version of the 2017 election where Clinton is President) doesn’t mean that they will anytime soon.

Virginia Sen. Time Kaine will be up for re-election in 2018, and given what we know right now he looks like a pretty solid bet. All major indicators (generic ballot polls, presidential approval, congressional retirements, special elections, etc) point towards a pro-Democratic national environment in 2018, and both the Cook Political Report and Sabato’s Crystal Ball rate Virginia’s Senate race as “Likely Democratic.” And there’s simply no way to know what the national environment will look like in 2020 when Sen. Mark Warner is up for re-election. Trump could be heading toward impeachment, riding high after winning a war with North Korea, slogging through the end of his term with an approval rating in the 30s or anywhere in between. We simply don’t know.

But what we do know is that the current indicators—including the off-year elections—point toward a favorable political environment for Democrats.

Correction: This article mistakenly claimed that Dean Heller was elected to the Senate from Nevada in 2014. He was elected in 2012. It also incorrectly stated the Rhode Island had a GOP governor.