It was once common knowledge, the story of Benedict Arnold—that extraordinarily successful patriot general who abruptly turned against the American Revolution. Because he had been so trusted by George Washington, Arnold was regarded as the worst of traitors. Indeed, his very name became synonymous with treachery and treason. Not so anymore. Nowadays many young Americans have no idea who Arnold was, and even those who have vaguely heard of the name have little sense of what he did and why “Benedict Arnold” has been a byword for betrayal through much of our history.

This loss of memory comes in part from a changing view of the revolution. In the hands of present-day teachers and professors the revolution is no longer the glorious cause it once was. It is now mostly taught—when it is taught at all—as a tale of woe and oppression, redressing what many academics believe was an overemphasis on the patriotism of great white men. “Those marginalized by former histories,” writes the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Alan Taylor in a recent introduction to current scholarship, “now assume centrality as our stories increasingly include Native peoples, the enslaved, women, the poor, Hispanics, and the French as key actors.” In his own narrative of the revolution, American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804, Taylor has painted a bleak picture of the event. Most of the patriots were not quite as patriotic as we used to think. The Southern planters, for example, engaged in the revolution principally to protect their property in enslaved Africans, but “implausibly blamed the persistence of slavery on the British.” Ordinary white men were even worse. In the West, where the fighting was especially vicious and bloody, they tended to run wild and slaughter Indians in pursuit of their “genocidal goals.” In the end, writes Taylor, it was a white man’s revolution whose success came at the expense of everyone else—blacks, Indians, and women.

No doubt this dark and sordid side of the revolution needs to be exposed. But unfortunately, this exposure has become so glaringly dominant nowadays that there is little room for the older, more patriotic story to be appreciated. Modern scholars haven’t gone so far as to describe Benedict Arnold as a hero for turning against this rather squalid and nasty revolution—after all, the side to which he defected was by their standards of judgment not appreciably different from the side he left—but since patriotism doesn’t have the appeal it used to have, Arnold’s treason seems not to matter as much anymore.

Yet of course it does matter, which is all the more reason to welcome another account of Arnold’s career, written, as many of the best and most readable histories of the revolution are written these days, by an independent scholar who is not caught up in the academic world’s obsessions with race and gender.

Stephen Brumwell is a British scholar who has written a number of important works on 18th-century military history, including a prize-winning book on George Washington. With his new book Turncoat: Benedict Arnold and the Crisis of American Liberty, Brumwell has added one more account to the multitude of works written over the past two centuries on this incident of treason. Perhaps Americans’ long fascination with Arnold and his treason can be explained in part by our need to define and emphasize our patriotism and nationalism. But its continual retelling can also be chalked up to the sheer drama of the story and its cast of extraordinary characters. There are spies and counterspies, suspense and close calls, a beautiful woman, a handsome and charming British major, and Alexander Hamilton. It’s amazing that Hollywood hasn’t made a serious effort to adapt the story for the screen.

Benedict Arnold was born in Connecticut in 1741, the son of a struggling petty merchant. From the outset Arnold was determined to make something of himself and establish his gentility. He was headstrong and prickly and not averse to cutting corners in order to make money. He quickly joined the revolutionary movement and at once displayed his capacity for aggressive military leadership. But he always felt his military achievements, which were considerable, were not properly acknowledged. Although he demonstrated his courage and his fighting spirit at Lake Champlain and Quebec—where his left leg was wounded by a ricocheting musket ball—his pushy and arrogant manner earned him a full share of enemies. In the spring of 1777 the Continental Congress promoted five brigadier generals to the rank of major general; Arnold was not among them, even though he had seniority in the Continental Army and a remarkable combat record. Although George Washington, as commander in chief, told Brigadier General Arnold that there must have been some mistake and begged him not to take “any hasty steps” before things could be worked out, Arnold, sensitive to any snub, was ready to resign his commission.

Arnold was slighted once again following the battles of Saratoga in September and October of 1777. Although General Horatio Gates, the cautious American commander, got credit for the surrender of thousands of British troops under General John Burgoyne, it was Arnold’s aggressive leadership that had actually determined the outcome. He was again wounded in action, having suffered another musket ball to his left leg, with the injury worsened when his killed horse fell on him. Saratoga was the turning point in the Revolutionary War. It led to the intervention of the French and to a major change in British command and strategy. But despite having done so much to bring about Burgoyne’s defeat, Arnold felt that his countrymen had not given him the recognition he deserved. (In fact, the British officers more fully took the measure of Arnold’s presence in the battle than did his fellow Americans.)

By 1778 Arnold’s sense of grievance and resentment had deepened. Because of his shattered leg, he could not take a field command; instead, he was appointed military commandant of Philadelphia. The city was not a healthy environment for inspiring patriotism. Hustling and shady business deals were everywhere, and Arnold, who had never been scrupulous about making money, sought to take advantage of these entrepreneurial opportunities. Politically the city was severely divided. During the year of British occupation in 1776-77, loyalist sentiment had flourished and was still very much present. But now austere radical patriots were back in control of the government, and they did not take to Arnold’s loose ways and his mingling with wealthy families of loyalist tendency. Arnold moved into the same elegant house on Market Street that the British commander had used, and he continued to host the same kinds of balls and dinners and patronize the same kinds of luxurious entertainments as the British had. The ascetic patriot radicals were not happy with this behavior, and they made Arnold’s life miserable by bringing criminal charges against him. Why, Arnold responded, should a wounded war hero have to suffer such harassment?

Inevitably the 37-year-old Arnold met Peggy Shippen, the beautiful 18-year-old daughter of one of the eminent loyalist-leaning families of Philadelphia. He persistently courted and finally married her in April 1779. Arnold’s restless ambition and his deep desire to amass wealth, especially to satisfy his wife’s expectations, led him into many devious dealings—for example, using government wagons to move private property. When he was severely criticized for his corrupt behavior, his accumulating resentments led him to rethink the meaning of the revolution. He concluded that his countrymen’s rejection of the Carlisle Commission in 1778, which had offered the Americans everything they had wanted in 1775, had been a mistake: America should never have left the British Empire.

Arnold then began to embark upon treason. Brumwell thinks that many historians have too readily attributed Arnold’s motivation to his thirst for gold. He quotes, for example, historian Willard Wallace’s observation that “more certain than any of Arnold’s reasons for selling himself to the British was his desire for money.” But actually Wallace wrote a few pages earlier in the same volume, his 1954 book Traitorous Hero, that “it is a distortion to contend that, simply because he needed money, he decided to sell out to the British.” Arnold certainly wanted to be well paid for turning his coat—£10,000 regardless of the outcome of the plot, plus an annual pension—but his motives were necessarily complicated, a product of years of accumulated gripes and resentments and jealousies. Brumwell emphasizes Arnold’s “gradual disillusionment with the Patriots’ political leadership, matched by a growing disenchantment at the changing nature and scope of the Revolutionary War,” especially the alliance with France. Brumwell tends to take Arnold’s explanations for his actions at face value.

The opportunity for committing treason came with his appointment to command West Point, a crucial fortification on the Hudson River north of New York City. Arnold worked out a plan not only to turn over the fort and its men to the British but at the same time to connive at the British capture of George Washington. By this point he wanted £20,000 for his treason.

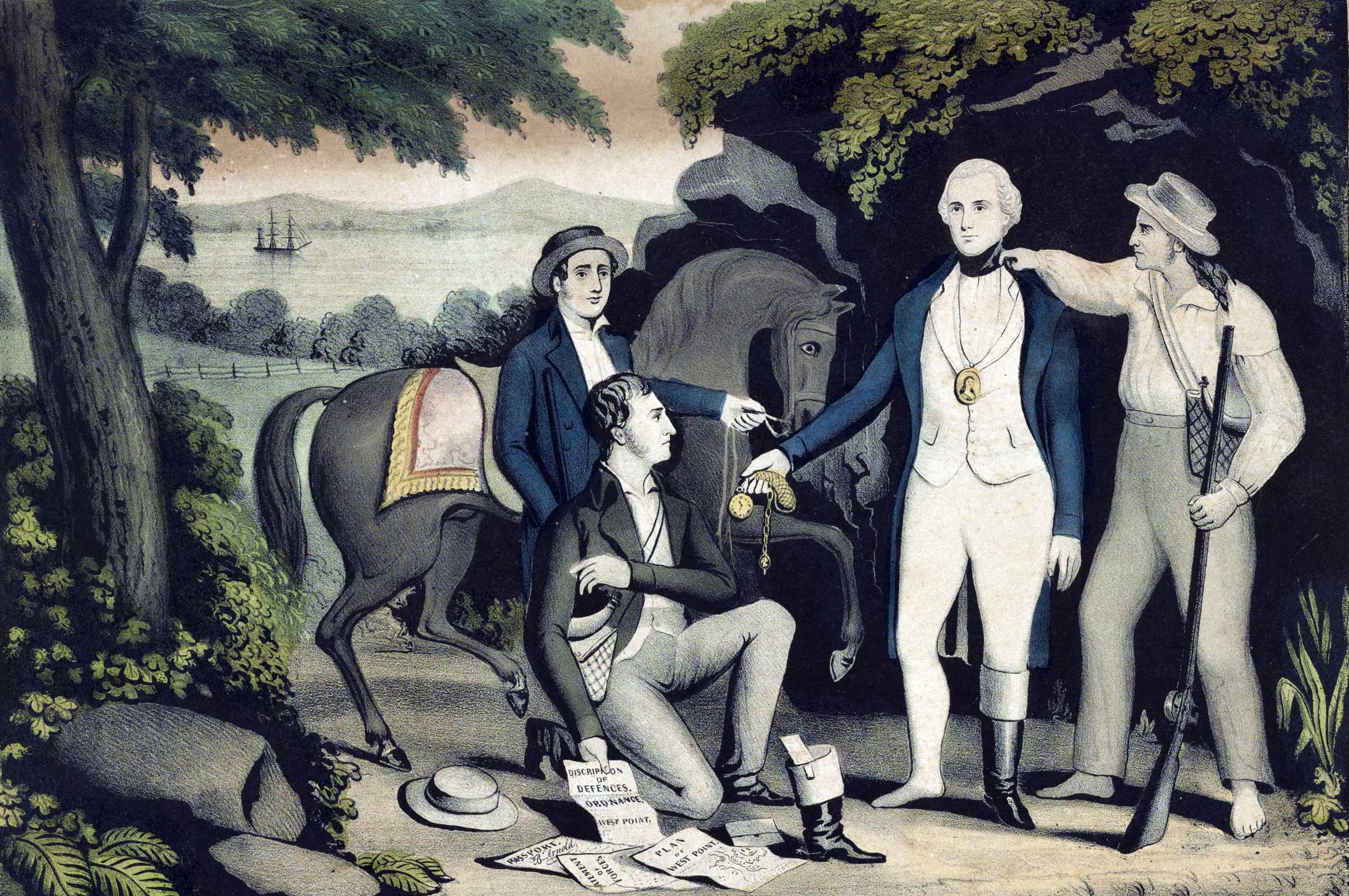

Arnold’s British contact was Major John André, an attractive young officer whom Peggy Arnold knew from the British occupation of Philadelphia. Following a meeting with Benedict Arnold in September 1780, André was forced to flee over land and thus had to shed his military uniform. When caught in civilian clothes with incriminating papers hidden in his boot, he was found guilty of spying, which meant execution by hanging. In the days following his capture André’s stoical behavior won the admiration of his captors, including Hamilton, who begged Washington to have André shot by a firing squad rather than hanged. Washington ignored such pleas and stood by the customary punishment for spying. As Arnold became the infamous American traitor, André emerged as a British martyr who in his final hours demonstrated the dignity and character of a real gentleman.

Learning of André’s capture, Arnold quickly fled to New York City, barely escaping Washington and his staff who were rushing to West Point. When the commander in chief arrived, Peggy went hysterical and convinced him and his entourage that she was innocent of Arnold’s plans. Washington and other patriot officers were stunned by Arnold’s treason. He was a senior officer who had fought valiantly on behalf of the cause; could anyone be trusted now? But the failure of the plot convinced Washington that once again Providence had saved the Americans from a disaster.

The British offered Arnold £6,000 and a royal commission as a brigadier general with an opportunity for promotion while fighting his former countrymen. And fight he did, spreading terror throughout Virginia and Connecticut with his aggressive raids. This took courage, for if he had been captured he would surely have been executed. But after Yorktown he could not persuade the British to continue the fight. They never used his considerable military talent elsewhere in the empire. It seems that he was never quite able to convince his new countrymen that he had always “acted from principle.” He died deeply in debt in 1801; Peggy followed three years later, of cancer at age 44.

Since this story has been told so many times over the past two centuries, it is difficult for any new work to alter the tale in any major way. But Brumwell suggests that Arnold’s plan to turn West Point over to the British, if successful, could have proved decisive in destroying the patriot cause. He argues that Arnold’s defection was not unique to him but was a symptom of a “widespread malaise affecting the patriot cause—a true crisis of American liberty.” By the early 1780s the Continental Army was underfunded, starving, and suffering from numerous desertions and mutinies. In order to properly understand Arnold’s treason, Brumwell says we must realize “that by 1780 many other Americans were equally disillusioned with the struggle for independence from Britain.” The revolution, he points out, was a civil war; allegiances were often fluid and shifting. Arnold was a peculiar sort of traitor: He always maintained that he had his country’s well-being at heart and that his fellow Americans should have accepted the terms of the Carlisle Commission and never allied with the obnoxious French. He was convinced, Brumwell writes, that his surrender of West Point to the British would “resolve a bitter, brutal, and divisive conflict with one devastating blow.” Brumwell admits that such an interpretation is “totally at odds with the prevailing consensus verdict on Arnold and his defining treason,” yet he says it “merits careful consideration within any balanced re-examination of America’s most infamous traitor.”

In his final chapter, “The Reckoning,” Brumwell concludes that “the loss of either West Point or Washington would undoubtedly have been a major setback for the patriot cause: the elimination of both might have forced Congress to capitulate.” This was Arnold’s view and one shared as well by many loyalists and British officials, including Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in chief. But it was never accurate. Too many loyalists and too many British officials from the beginning to the end lived with the illusion that the revolutionaries’ commitment to independence was superficial at best and that if the rebels ever suffered a serious setback they would surely seek reconciliation with the mother country. Arnold even suggested that Washington might be won over with the promise of a title. But by 1780 no matter how much discontent existed in the army, no matter how unwilling the states were to spend money, no matter how inflated the currency had become, most Americans were never going to surrender to British sovereignty. Even the capture of Washington would not have ended the struggle. Arnold was an aberration: No senior military officer followed his example and the desertions of American soldiers were never as great as the British expected. The American corporal that Arnold tried to bribe into joining him during his escape spoke for most common soldiers: “No, sir, one coat is enough for me to wear at a time.”