What separates science from other intellectual activities? The search for a distinctive logical structure of scientific inquiry and for the essence of scientific truth goes back at least to David Hume’s concerns with the limits of inductive inference (does the fact that the sun rose yesterday mean that it must rise tomorrow?) and has been pursued along a variety of philosophical lines. Perhaps best-known among such efforts is the falsifiability criterion devised by the Austrian-born philosopher Karl Popper, according to which science should be recognized not by the evidence it garners on behalf of one proposition or another (supporting evidence can be found for pretty much any proposition) but by the types of questions it asks—questions that can be empirically contradicted.

In Lost in Math, however, Sabine Hossenfelder, a physicist who is funny and writes with that slightly oblique flair sometimes found in totally fluent nonnative English writers, learns at a scientific conference that

Exactly.

What, then, joins Hossenfelder’s field of theoretical physics to ecology, epidemiology, cultural anthropology, cognitive psychology, biochemistry, macroeconomics, computer science, and geology? Why do they all get to be called science? Certainly it is not similarity of method. The methods used to search for the subatomic components of the universe have nothing at all in common with the field geology methods in which I was trained in graduate school. Nor is something as apparently obvious as a commitment to empiricism a part of every scientific field. Many areas of theory development, in disciplines as disparate as physics and economics, have little contact with actual facts, while other fields now considered outside of science, such as history and textual analysis, are inherently empirical. Philosophers have pretty much given up on resolving what they call the “demarcation problem,” the search for definitive criteria to separate science from nonscience; maybe the best that can be hoped for is what John Dupré, invoking Wittgenstein, has called a “family resemblance” among fields we consider scientific. But scientists themselves haven’t given up on assuming that there is a single thing called “science” that the rest of the world should recognize as such.

The demarcation problem matters because the separation of science from nonscience is also a separation of those who are granted legitimacy to make claims about what is true in the world from the rest of us Philistines, pundits, provocateurs, and just plain folks. In a time when expertise and science are supposedly under attack, some convincing way to make this distinction would seem to be of value. Yet Hossenfelder’s jaunt through the world of theoretical physics explicitly raises the question of whether the activities of thousands of physicists should actually count as “science.” And if not, then what in tarnation are they doing?

What’s worrying Hossenfelder is that theory-making in fundamental physics is being driven not by experimental confirmation of key hypotheses but by subjective criteria of aesthetics. Physicists use words like “beauty,” “simplicity,” “naturalness,” and “elegance” to describe the ineffable sense that the mathematics explaining a theory just feels right, and they believe that such aesthetically satisfying theories are more likely to describe reality than those that feel ad hoc or contrived.

Galileo called math the language of nature, but the extent to which this is really true—that there is something about the structure of natural phenomena that necessarily corresponds to the logic of mathematical statements—is a question that scientists and philosophers continue to debate. As Hossenfelder observes, “Mathematics is full of amazing and beautiful things, and most of them do not describe the world.” She worries that theoretical physicists are busy discovering “numerological coincidences” rather than accurate descriptions of reality.

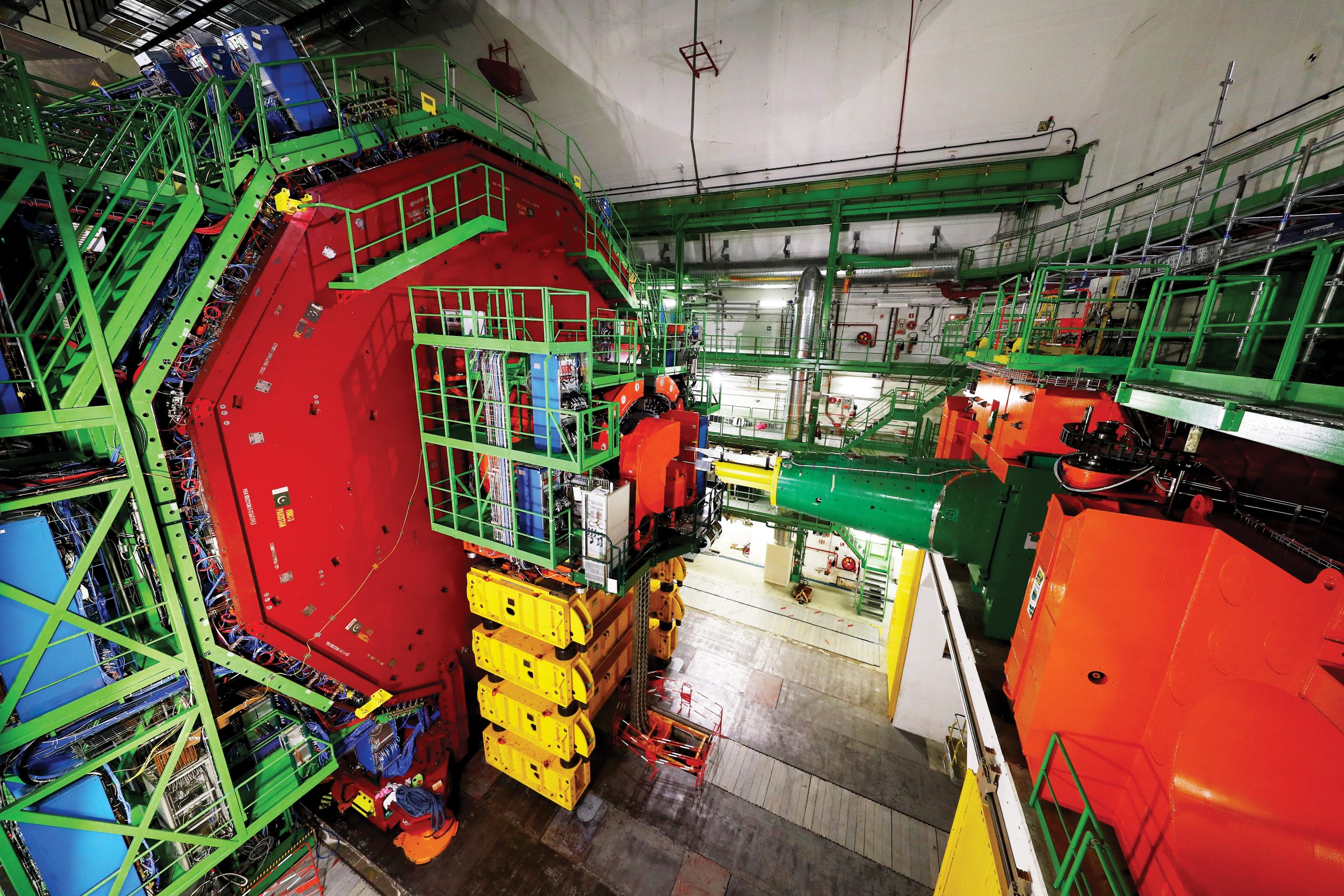

Surprisingly, an important marker of the divergence between theory and experiment that concerns Hossenfelder is the most famous experimental discovery of recent decades, the confirmation of the existence of the Higgs boson by scientists using the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland. Science magazine named the Higgs its “Breakthrough of the Year” in 2012:

According to the New York Times, the Higgs discovery confirms “a grand view of a universe described by simple and elegant and symmetrical laws—but one in which everything interesting, like ourselves, results from flaws or breaks in that symmetry.” Whatever that means—but I’ll come back to the question of meaning later.

As Hossenfelder explains, however, if the experimental confirmation of the Higgs prediction was a spectacular validation of the standard model (which explains how subatomic particles and fundamental forces interact), it was accompanied by a failure to make discoveries necessary to support another fundamental theory of physics, known as supersymmetry, or “susy.” This is a problem because “one of the main motivations” for developing susy has been to help explain a major inconsistency in the standard model: While the standard model dictates the existence of the Higgs boson, the theory also requires that the particle’s mass be enormously greater than it seems actually to be. To deal with this discrepancy one could “amend the theory” to give the right mass, but that requires that the number be fudged to exactly counterbalance the mass discrepancy. This sort of ad hoc tuning of numbers offends the sense of mathematical beauty and naturalness that physicists strive for in their theories. Susy takes care of that problem by predicting other particles, “superpartners,” that can counterbalance the excess mass of the Higgs by just the right amount so that the mass doesn’t have to be fudged in what seems like an arbitrary way. This appeals to physicists because it feels “natural.” It doesn’t require ad hoc adjustments to numbers to get the mathematically determined Higgs mass to conform to the observed mass.

If susy is correct, then evidence for superpartners should have shown up in the Large Hadron Collider. It hasn’t. This can mean one of two things. Most of the physicists Hossenfelder talks to in her book think it means that supersymmetry theory needs to be tweaked a bit to explain why the expected particles remain undiscovered—that perhaps susy is not so “natural” after all. As physicist Keith Olive tells Hossenfelder, “It’s certainly true that we expected susy at lower energy. It’s a big problem. There’s something in me that tells me that supersymmetry should be part of nature, though, as you say, there’s no evidence for it.”

The other possibility is that the theory is wrong. Hossenfelder jets around the world talking to physicists about the challenges facing the field, but few seem willing to seriously entertain this option. “It’s either me who’s the idiot,” writes Hossenfelder, “or a thousand people with their prizes and awards.”

And there’s a time-honored way for those thousand scientists to avoid coming to grips with the second possibility: Do more research. Build another, bigger, more expensive collider to look for even heavier particles to rescue beautiful susy. “I’m not sure which I find worse,” Hossenfelder writes, “scientists who believe in arguments from beauty or scientists who deliberately mislead the public about prospects of costly experiments.”

She has similar tales to tell about string theory and the quest to detect dark matter particles—which she hilariously summarizes in a list of 40 or so failed experiments with names like EDELWEISS, ROSEBUD, and PICASSO (not to mention IGEX, GEDEON, and XENON100). Her courageous if not always fully comprehensible effort to uncover not just the hidden assumptions but also group behavior behind theoretical physics forces the question of demarcation. “Someone needs to talk me out of my growing suspicion that theoretical physicists are collectively delusional, unable or unwilling to recognize their unscientific procedures.” If their procedures are “unscientific,” are they doing science?

When Hossenfelder writes about “science” or the “scientific method” she seems to have in mind a reasoning process wherein theories are formulated to extend or modify our understanding of the world and those theories in turn generate hypotheses that can be subjected to experimental or observational confirmation—what philosophers call “hypothetico-deductive” reasoning. This view is sensible, but it is also a mighty weak standard to live up to. Pretty much any decision is a bet on logical inferences about the consequences of an intended action (a hypothesis) based on beliefs about how the world works (theories). We develop guiding theories (prayer is good for you; rotate your tires) and test their consequences through our daily behavior—but we don’t call that science. We can tighten up Hossenfelder’s apparent definition a bit by stipulating that hypothesis-testing needs to be systematic, observations carefully calibrated, and experiments adequately controlled. But this has the opposite problem: It excludes a lot of activity that everyone agrees is science, such as Darwin’s development of the theory of natural selection, and economic modeling based on idealized assumptions like perfect information flow and utility-maximizing human decisions.

Of course the standard explanation of the difficulties with theoretical physics would simply be that science advances by failing, that it is self-correcting over time, and that all this flailing about is just what has to happen when you’re trying to understand something hard. Some version of this sort of failing-forward story is what Hossenfelder hears from many of her colleagues. But if all this activity is just self-correction in action, then why not call alchemy, astrology, phrenology, eugenics, and scientific socialism science as well, because in their time, each was pursued with sincere conviction by scientists who believed they were advancing reliable knowledge about the world? On what basis should we say that the findings of science at any given time really do bear a useful correspondence to reality? When is it okay to trust what scientists say? Should I believe in susy or not? The popularity of general-audience books about fundamental physics and cosmology has long baffled me. When, say, Brian Greene, in his 1999 bestseller The Elegant Universe, writes of susy that “Since supersymmetry ensures that bosons and fermions occur in pairs, substantial cancellations occur from the outset—cancellations that significantly calm some of the frenzied quantum effects,” should I believe that? Given that (despite my Ph.D. in a different field of science) I don’t have a prayer of understanding the math behind susy, what does it even mean to “believe” such a statement? How would it be any different from “believing” Genesis or Jabberwocky? Hossenfelder doesn’t seem so far from this perspective. “I don’t see a big difference between believing nature is beautiful and believing God is kind.”

Suppose, then, we lower our sights and focus on a problem a bit less lofty than the fundamental structure of the universe, like, say, antifreeze. That’s the example Jeremy J. Baumberg offers in The Secret Life of Science to help “see the richness of approaches to science more clearly.” As part of the quest for new and improved antifreeze, some scientists might simply test “how much antifreeze is needed in different weathers”; others might aim at “predicting performance of different types of cooling fluids”; still others might explore the behavior of different “liquids when heated and cooled in pressurized flows”; and so on. While The Secret Life of Science aims to expose some of the intractable problems that beset the scientific enterprise, Baumberg wants to make quite clear from the outset that whatever science’s “flaws” may be, “they do not fundamentally undermine [science] because of the self-correcting way that it works.” This view is reasonable when applied to Baumberg’s antifreeze model of science because theory, experiment, and application all inform and act as checks on one another. If the underlying science isn’t right the antifreeze won’t work.

Unlike Hossenfelder, then, Baumberg isn’t troubled by problems with scientific inquiry itself, since he thinks it automatically self-corrects. Yet he does believe that science is in “a state of some crisis” due to a variety of external forces and incentives, especially hypercompetition for funding, jobs, and media attention. He sees reduced diversity and flexibility in the ways science is conducted and he worries that science is often aimed too narrowly, too often captured by fads and bandwagons, and too much dominated by “the scientist who is highly aggressive and aggrandizing.”

While generally sensible, Baumberg’s book is marred both by a dearth of references to background research materials that could support these sorts of general assertions and by an absence of rich examples and illustrative anecdotes that could give life and conviction to his critique. The result seems both off-the-cuff and bloodless, an odd combination. Baumberg’s discussion comes more to life in the few places where he does call upon his own experiences, for example in a brief reference to work he did at Hitachi on optical switches, which he uses to illustrate a broader point about the increasingly close ties between scientific advance and the quest for media coverage. But such instances are rare, which is too bad because he obviously has rich and deep experience in both industrial and academic research settings.

The Secret Life of Science is also an illustration of why the problem of demarcating science from nonscience matters. Building on his antifreeze example, Baumberg asserts his own demarcation criterion: “As long as new knowledge is built by creative systematic novel inquiry, it seems right to me to call all of it science.” He quickly gets ensnared in contradictions, however, because new knowledge is supposed to demonstrate “testability or repeatability.” This means he has to make special allowances for “a distinct class of hard science problems” that are “hardly amenable to testability,” in such fields as cosmology, neuroscience, and particle physics, which apparently he does not want to exclude from the temple of science. But what of the social sciences, or the sorts of interdisciplinary fields that use complex mathematical models to try (and generally fail) to predict phenomena like economic cycles or future energy consumption, or the sorts of statistics-heavy fields that seek to tease out the links between a toxic chemical and cancer or between a teaching method and grade-school achievement? Such efforts merit nary a mention as part of science’s secret life. Are they excluded from the grand temple because the knowledge they produce is “hardly amenable to testability,” often remaining highly uncertain and strongly contested for decades? But then why should susy and string theory get a free pass?

Were he to broaden his definition of science beyond the antifreeze model, Baumberg’s portrayal of a crisis in science caused by forces external to it would be much harder to sustain. It’s one thing for theoretical physicists to chase the wrong theory about fundamental particles for 25 years with nothing to show for it but high-prestige publications. That’s fun. But what can be said after a long series of clinical trial failures suggests that neuroscientists have been chasing the wrong theory for Alzheimer’s disease for 25 years with nothing to show for it but high-prestige publications? When hundreds of published breast-cancer studies turn out to be based on contaminated samples, when thousands of brain-imaging studies turn out to be statistically flawed, when economic theory continues to build on assumptions about human behavior that are known to be wrong, it becomes rather difficult to understand how one can separate self-correction from bad science from nonscience from delusion from corruption.

Scientists should pursue hard problems, and society will depend, increasingly so, on the results of their inquiries. But even the most abstract and recondite scientific knowledge may reflect very human assumptions about how the world works—for example, that the behavior of the universe is best described by elegant mathematical logic. Science cannot be cleanly demarcated from nonscience, and much of what we are hoping that scientists can tell us these days—about nutrition and health, about economics, the environment, education, aging, and the origins of the universe—will emerge from the vast fuzzy area between the two. Arguments over the results and implications of such work will be never-ending and will be peppered with accusations that one side or the other is being unscientific. What we nonexperts choose to believe about such matters will depend much more on whom we trust and what we find to be helpful than on what can be known to be true.