When Doris “Dorie” Miller fired at Japanese fighters with an anti-aircraft gun during the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he wasn’t just protecting his ship and crew — he also paved new ground for black sailors in the Navy.

For his bravery, Mess Attendant 2nd Class Miller was awarded the Navy Cross, the Navy’s second-highest decoration, and soon will have an aircraft carrier named after him. The Navy is expected to announce the naming today during a ceremony at Pearl Harbor in conjunction with Martin Luther King Jr. Day. But Miller’s legacy goes beyond Pearl Harbor. He also unwittingly helped spur major reforms in the Navy, which for decades placed significant restrictions on black sailors.

The Navy was segregated when Miller enlisted. Serving in the ship’s mess was one of the only jobs available to a black man. When Japan attacked the Pearl Harbor fleet on Dec. 7, 1941, chaos descended. “While at the side of his Captain on the bridge, Miller, despite enemy strafing and bombing and in the face of a serious fire, assisted in moving his Captain, who had been mortally wounded, to a place of greater safety,” reads the citation for Miller’s Navy Cross. He “later manned and operated a machine gun directed at enemy Japanese attacking aircraft until ordered to leave the bridge.”

“It wasn’t hard. I just pulled the trigger, and she worked fine,” Miller later recalled. “I had watched the others with these guns. I guess I fired her for about 15 minutes. I think I got one of those Jap planes. They were diving pretty close to us.”

Miller became an overnight celebrity following Pearl Harbor, especially among black communities across the country, some of which pushed for him to receive the Medal of Honor. His Navy Cross was awarded by Adm. Chester Nimitz, the commander of the Pacific Fleet who would go on to become a war hero in his own right. Miller was the first black man to receive the medal.

“This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race, and I’m sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts,” Nimitz said.

Recognizing his importance to the war effort, the Navy sent Miller on a war bond tour, as it did with other war heroes at the time. His likeness was also used in a now famous recruiting poster featuring the words “above and beyond,” along with Miller in his dress white uniform and Navy Cross.

Miller was promoted to cook third class and returned to ship duty in 1943 aboard the USS Liscome Bay. He was killed, along with 646 others, when a Japanese torpedo ignited the ship’s aircraft bomb magazine on Nov. 23. 1943. He was 24 years old.

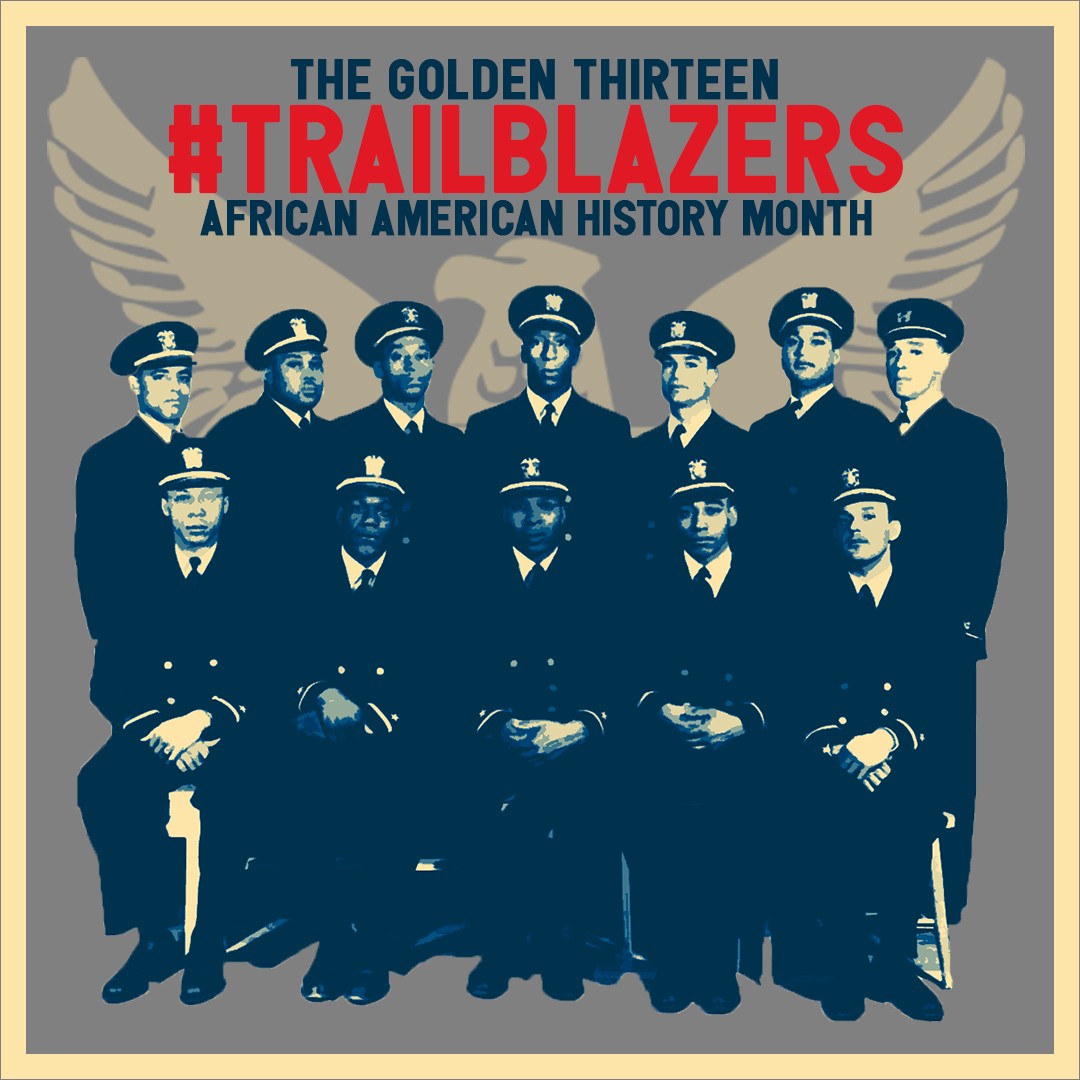

Four months later, the Navy graduated its first black officers, known as the Golden 13. Prior to that time, black men were limited to enlisted positions, usually working in menial jobs in the mess, as Miller did. Previously, between the end of World War I and 1932, black men weren’t allowed to join the service.

The Army graduated its first black officer, 2nd Lt. Henry Ossian Flipper, nearly 70 years prior, but black Army recruits faced prejudice. The Tuskegee Airmen, famous for becoming the first black fighter squadron in World War II, were denied entrance to officer’s clubs despite their exemplary service.

Despite their status as officers, the Golden 13 also faced prejudice and were “treated more as pariahs than pioneers,” according to the U.S. Naval Institute. Like their enlisted counterparts, the Golden 13 often were limited to menial jobs but paved the way for future generations. In 1945, the Marine Corps commissioned Frederick Branch, its first black officer.

President Harry Truman officially desegregated the military in 1948, opening up opportunities for troops across all the services. By that time, Doris Miller was five years dead. His name is listed on the panels for the Courts of the Missing in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii.

[Opinion: The woke Left vs. Martin Luther King Jr.]