By the time Nikolas Cruz opened fire at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School on Feb. 14, killing 17, he had given every warning of what he planned to do.

But to put it that way understates the egregious failure, at every level, by the adults responsible for protecting the students. An awful lot of people had to fall down on the job. Once you spell out the parade of failures that preceded the shooting, it’s much harder to buy into the cry for gun control that followed it.

Cruz, a former student at the school, had been transferred out — inexplicably not expelled — for a myriad of behavioral issues, including his having brought bullets to school in his backpack. Somehow, this offense did not merit a more robust intervention. Some conservatives have asked whether this was a result of a 2014 Education Department directive intended to reduce suspensions and expulsions of minority students.

Either way, Cruz should have been on everyone’s radar, especially when he started posting online threats to shoot up the school. And even before that, it isn’t your average juvenile delinquent whose behavior generates 45 calls to the sheriff’s department and at least 23 visits by deputies over a 10-year period.

[Also read: 8 races where gun control is front and center]

In the months before he massacred his former schoolmates, Cruz was very obvious with his online threats and could have easily been arrested for them several times. Two years before the killings, he should have been committed as a danger to himself and others, which would have prevented his purchase of firearms.

In hindsight, Cruz could never have taken 17 lives and injured 17 others if not for the combination of false compassion, leniency, and neglect shown by federal, state, and especially Broward County officials.

The sum of their errors and negligence was probably too much for any gun control proposals offered in the aftermath to remedy.

Early warnings

As early as February 2016, the Broward County Sheriff’s Office had been told about Cruz’s threats on Instagram to shoot up his school.

They came complete with pictures of his guns, showing he had both the intent and the means to carry it out. The information was forwarded to the school resource officer, a sheriff’s deputy, who apparently did nothing.

In September 2016, Cruz had acquired a habit of self-cutting and was suspected of swallowing gasoline in a suicide attempt. Despite this, a mental health counselor at the school advised against committing him involuntarily for psychiatric care — a fateful decision that meant he would be able to buy and own guns legally.

School authorities were not alone in this mistake, either. Less than a week later, Cruz reportedly had fresh self-inflicted cuts on his arms when an investigator from the Florida Department of Children and Families ruled that his mental state was “stable.”

On Nov. 1, 2017, the day Cruz’s adoptive mother died, her cousin called the Broward sheriff’s office, begging them to take Nikolas’ guns away and put them in the possession of another family member. A month later, sheriff’s deputies received a tip that Cruz was stockpiling weapons and “could be a school shooter in the making.” The deputies refused to make a report, instead telling the tipster to take his concerns to the sheriff of neighboring Palm Beach County, where Cruz was living at that point.

Even the FBI had been tipped off about Cruz. Last September, someone called their Mississippi office to report a YouTube user with the handle “nikolas cruz” boasting on YouTube about his plan to become a “professional school shooter.”

And this January, the FBI was tipped off again about Cruz’s “gun ownership, desire to kill people, erratic behavior, and disturbing social media posts, as well as the potential of him conducting a school shooting.” Somehow, this information never found its way to the bureau’s Miami office.

To cap off this very unfunny comedy of errors, as the shooting was occurring, the armed Broward deputy who served as the school’s resource officer cowered outside the door, refusing to enter and confront Cruz, if not to shoot him, then at least to pin him down and prevent further bloodshed.

A Polished Operation

It’s hard to feel anything but sympathy for the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas, given that nearly every adult authority figure responsible for protecting them dropped the ball. Professional Democratic partisans understood this and were quick to take advantage more effectively than they had after any previous shooting.

Behind the scenes, the tragedy in Parkland, Fla., will surely change the way school security is handled, and of course the way mental health cases like Cruz’s are handled in the future.

But in public, and especially on television, there has been only one topic of discussion: The surprisingly polished and well-organized political campaign for gun control that a number of Parkland students have become part of.

Yes, the March for Our Lives movement is a bit too polished and organized for well-meaning high school kids to have created it on their own, because they didn’t. It came together when former DNC Chair and Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Fla., along with political advocates at Planned Parenthood, MoveOn.org, the Women’s March, the gun control group Everytown for Gun Safety, and the American Federation of Teachers, quickly and smartly harnessed the power of these young and sympathetic figures.

These groups invested the resources, set up the interviews, and staged the events. Their investment, which went almost completely unreported for weeks, paid dividends, giving the cause of gun control a prominence it hasn’t enjoyed since the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting.

The students given the most prominent roles in this movement have largely cooperated with their sponsors’ partisan id, conspicuously shrugging off the grave mistakes by local Democratic officials that led to the tragedy, and instead training most of their ire on Republican Sen. Marco Rubio (complete with attacks on his Catholic faith), who is still viewed as a potential presidential candidate.

Rubio has weathered the attacks well enough, co-sponsoring constructive bipartisan legislation. But can the status quo on gun rights survive this assault? In a sign of how quickly the Parkland students shifted the conversation, Florida Republicans wasted no time in raising the state’s minimum age for rifle purchases to 21, to match the age for buying handguns. Rep. Brian Mast, a Republican congressman hailing from the Treasure Coast, a bit north of Parkland, had received support from the National Rifle Association during the 2016 cycle, but now he is calling for a ban on the AR-15, the civilian style of rifle that Cruz used.

On the national level, there is now talk of banning the AR-15, the nation’s most popular rifle, restoring the federal assault weapons ban, and expanding background checks. For all of the freshness of their new faces, the Parkland students and the March for Our Lives drove the debate straight into the same rut in which every gun debate before it has ended up.

And despite the high hopes of the anti-gun campaigners, their proposed solutions probably won’t get any further than they have in the past.

Gun control in the U.S. is one of those issues where partisans have talked past one another for as long as anyone can remember. Nothing is about to change this. And it’s a shame, because there is actually more room for agreement than people think.

The traditional gun rights argument is that even minor restrictions on Second Amendment rights represent the camel’s nose under the tent and must be resisted at all costs. The argument is based on principle: This freedom to own and carry a personal weapon, passed down from the English common law, should not be taken away, even if there exist data suggesting that its curtailment might have a large-scale beneficial effect, such as saving some number of lives nationwide each year.

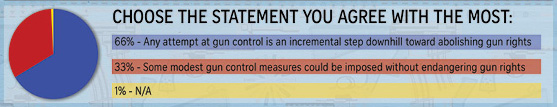

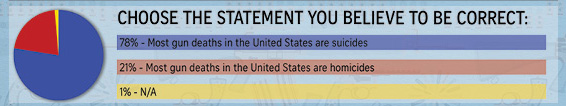

In an unscientific survey we conducted last month of more than 1,000 of our readers, we found that two-thirds of them subscribe to this point of view — as do I. The only problem is that if you don’t accept the premise about freedom superseding other goods when it comes to government policy, you will never be persuaded. And in an era when the Left has also been challenging basic civic assumptions about the value of other freedoms such as the First Amendment, the potential for common understanding on that score might be disappearing for good.

There’s also a more practical argument for respecting gun rights. In a country with more privately owned guns than there are people, the only way to deal with the presence of firearms is to accept it and move on from there. The ubiquity of firearms means that even if the Second Amendment were repealed and a ban on gun sales went into effect today, it could be the better part of a century before anyone noticed a difference in outcomes.

The only other option, confiscation, is not feasible. And if deporting 5 million illegal immigrants is impossible, imagine the idea of confiscating 325 million guns from their owners.

On the gun control side, there are some decent and sensible arguments. But as it is made publicly, the case for gun control consists mostly of emotion and intuition occasionally disguised as data.

Strip away the emotional appeals, and you begin with a reasonable-sounding premise: Without any guns, there would never be any shootings. And that’s fine, but the conclusion that most adherents draw from this is that incremental limits on gun ownership should therefore incrementally limit shootings. And that simply doesn’t follow.

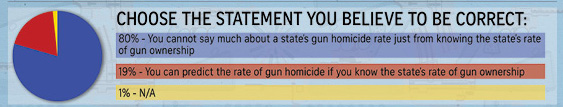

Nor does it appear to be true. In theory, if stricter gun control laws are supposed to result in significantly lower rates of gun homicide, then we’d expect to see differences within the 50 states that have some relation to their varied gun laws. If gun control laws had a downward effect on gun murders, we’d at least expect to see Texas, where “gun control” simply means using both hands, with a consistently higher rate of gun homicides than a similarly large state with strict gun control like California. Yet, the opposite has been true for three of the last five years for which there are data, according to FBI and the U.S. Census.

Obviously, that isn’t a scientifically valid observation with two-way multivariate analysis. But the mere fact that these two states (America’s two largest sample sizes) are in the same ballpark poses a serious challenge to the theory that gun control works, and places the burden of proof on those who would take away others’ rights. Just to name a few other odd-couple states based on the 2016 data: Rhode Island and Idaho have similar rates of firearm homicides; as do New Jersey and Arizona; Connecticut and Iowa; Illinois and South Carolina; Maryland and Tennessee. It’s almost as if there’s no obvious connection between the strictness of a state’s gun control laws and the number of people murdered there with guns.

Not only do such popular misconceptions abound, but the argument for gun control often relies on them to do most of the work, both in making the case for gun control and in deriving the movement’s policy prescriptions.

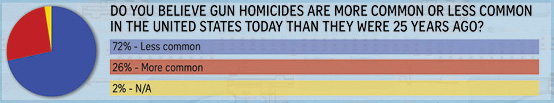

For example, the most common piece of misinformation in the wake of Parkland has been the idea that a change is urgently necessary right now because gun violence is rapidly increasing. A close second is that American schools are now unsafe. Even 26 percent of our own readers, who tend to be very supportive of gun rights, fell for this media-driven idea that gun homicides are “more common” today than they were 25 years ago.

But the federal Centers for Disease Control report the opposite. Gun homicide rates fell by nearly 50 percent between 1993 and 2013. And although that rate has crept back up since 2013, the 4.0 gun murders per 100,000 people of 2015 was quite an improvement over the 7.0 rate of 1993.

As for school shootings, they are still incredibly rare. The FBI’s recent report on “active shooter” incidents (these include incidents that fit both Congress’s three-victim definition and the more traditional four-victim definition of mass shooting) found 39 of them at schools (including colleges) between 2000 and 2013, with a total of 117 fatalities over those 14 years. Even one such death is too many, of course. But the same number of teenagers (13 to 19 year-olds) killed at schools over those 14 years was killed in road accidents every 14 days in 2016. Statistically speaking, your daughter is nearly a thousand times safer from shooters at school than she is from the drive there and back. She’s also more likely to be killed in a lightning strike (as about 50 Americans are every year) than by bullets from a school shooter’s gun at her place of learning.

Because the gun control debate always operates on the false assumptions that gun violence has become more common, and that mass gun killings are an everyday occurrence, it’s no surprise that the proposed solutions behind gun control often don’t match the real-world issue of gun violence.

For example, take the narrow focus on so-called “assault weapons.” “Assault weapon” is not even a real term — it is a political buzzword created by legislators who wanted to make certain kinds of guns sound especially scary.

“Assault weapons” were defined as guns (mostly rifles) with certain cosmetic features that give them a military look, even though their functionality often doesn’t differ from some non-“assault weapons.” Nevertheless, turn on the television, and you’re likely to hear journalists and supporters of gun control talk about “assault weapons” as if they are superweapons that can fire multiple bullets at once and mow everyone down. In fact, the often misunderstood term “semiautomatic” simply means that a gun can fire one bullet at a time, without being recocked between rounds.

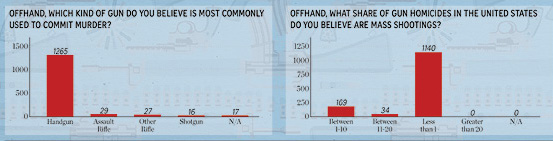

In the real world, military-style rifles are not that great a danger. Consider that nearly the same number of handguns as rifles are sold in the U.S. each year (the ratio is about 5 to 4, according to the ATF). Yet, rifles as a whole — not just this particular kind — accounted for only 374 murders in 2016 and less than 300 in each of the three preceding years, out of 12,000 to 15,000 total annual murders, according to the FBI.

When it comes specifically to mass shootings, gun control advocates simply leave out the fact that two-thirds of the weapons used in those (94 out of 143, by Mother Jones’ count between 1982 and 2012, using a four-victim definition) were handguns, not rifles. And so, the tendency appears to be that we frame gun policy primarily based on one particularly rare kind of shooting, with a specific style of gun that is not even usually used in those incidents, based more on an emotional than a factual response. Such an approach is susceptible to the criticism that it merely threatens the rights of many law-abiding people without being fact-based or having demonstrated potential to save lives.

If you wanted to put a serious dent in shootings via gun control, you would have to focus on handguns. According to FBI data, they made up 88 percent of gun murders in 2016 in which the specific type of gun was reported. In contrast, FBI data say you’re almost twice as likely to be beaten to death with someone’s fists or feet as to be killed with any rifle at all, let alone an AR-15 or a so-called “assault weapon.”

So, why do gun control advocates zero in on rifles that have pistol grips or bayonet mounts each time they see a chance to advance gun control? Do the other 95 percent of gun homicides matter less? Do they just enjoy antagonizing gun owners? Or is it just a random response to the emotional appeal of a scary gun?

This puzzling incongruity, and others like it, speak to a “just do something, anything!” mentality — a tendency among gun control advocates to choose solutions based on feelings, hunches, a desire to antagonize gun owners — anything but potential effectiveness.

One of the more reasonable ideas that gun control advocates offer is mandatory universal background checks. At some point, a compromise will likely be adopted on this issue — perhaps the free, voluntary background check system that former Sen. Tom Coburn, R-Okla., proposed for private sales after Sandy Hook, which our editors endorsed in 2015.

But even universal background checks would do a lot less than advertised. Go back through the catalog of recent mass shootings, and not a single case turns up in which this would have prevented a fateful purchase leading to a mass killing — that is, a case in which a future shooter who would have failed a federal background check avoided it by making a lawful intrastate private gun purchase that didn’t require a background check in one of the 31 states that allow such sales.

Bipartisan Solutions

According to FBI and CDC numbers, gun murders are way down over the last two decades. So are non-fatal shootings and the use of guns in other violent crimes such as robbery and assault. This is the trend, even though the number of privately-owned firearms has continued to climb.

Meanwhile, mass shootings remain too common, even though they are extremely rare events.

So, the sensible, practical, and data-driven way of finding middle ground on this issue should be to seek policies that can further reduce the small and shrinking threat that guns pose to innocent bystanders without infringing the Second Amendment rights of tens of millions of Americans who will never shoot anyone.

Believe it or not, there are good answers to this. Congress is even considering some of them. There is a lot more common ground on this issue than partisans of either side would like to admit, if only they’ll step back and acknowledge it.

The first area to examine is the worst point of failure when it comes to mass shootings: The existing instant background check system. What we have now is a shoddy disaster, whose incompleteness and mismanagement has cost the lives of at least 68 people since 2007.

Although politicians’ focus has been on injecting the FBI into every private sale between one cabin owner and his neighbor in the mountains of Idaho, those sales have never been the problem. The problem has been that when gun buyers are checked by licensed dealers, their files in the NICS databases are missing key information, or else government officials neglect to look in the right place.

Such omissions allowed two recent and infamous church shooters — in Charleston, S.C., and Sutherland Springs, Texas — to buy the guns they used in their mass shootings.

Both should have been ineligible to buy guns due to convictions. Likewise, such an omission allowed the shooter in the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre (who killed 32 people) to buy a gun despite having already been deemed mentally incompetent by a judge. Unfortunately, information on his mental health status had not been entered into the federal database.

Those three shootings alone account for 68 fatalities — more than 10 percent of the mass shooting deaths since 2007. Take that as a sign that background checks can actually work under the current legal regime to reduce mass shootings — but not unless we commit the resources and overhaul the system so that they are done right.

Congress passed the bipartisan Fix NICS Act as part of the recent omnibus bill, to improve reporting and compliance so that NICS contains the information it needs. That’s a good start, but lawmakers can’t stop until they are satisfied that the problem is really solved. They already passed another bill to improve NICS after the Virginia Tech shooting, and obviously, that effort wasn’t good enough. To save lives with background checks, Congress has to keep its eye on that ball and appropriate more money if necessary.

A second area to fix, also worth approaching with a bipartisan spirit, is the perennial lack of enforcement against ineligible purchasers who lie and try to buy guns. When a background check application is rejected, it means the applicant lied and should face prosecution. But although this happens about 70,000 times per year, the Department of Justice under both Democrats and Republicans has historically prosecuted only a few dozen such “lie and try” cases.

The NICS Denial Notification Act, which has multiple liberal and conservative sponsors in both houses of Congress, would change this. It would require the FBI to notify state and local officials every time someone fails a background check so that they can be prosecuted quickly. In the meantime, Attorney General Jeff Sessions has promised to put federal prosecutors on the case.

If felons and those deemed dangerous feel the certainty that an attempted gun purchase will result in prosecution, tens of thousands of people who shouldn’t own guns will be discouraged from trying to buy them. Meanwhile, advocates for public safety should be pressuring their state legislatures to enhance penalties and set aside money for such prosecutions.

A third consideration that comes up in Nikolas Cruz’s case will perhaps require a more lengthy discussion. The U.S. has to rethink how we handle people who suffer from threatening and dangerous forms of mental Illness — acknowledging that not all forms of mental illness are dangerous.

Despite recent attempts to downplay the connection between mental illness and mass shootings, research strongly supports the link. Grant Duwe, the research director for Minnesota’s Department of Corrections, and Michael Rocque, a sociology professor at Bates College, wrote recently in the Los Angeles Times that as many as 59 percent of mass shooting events between 1900 and 2017 “were carried out by people who had either been diagnosed with a mental disorder or demonstrated signs of serious mental illness prior to the attack.”

They also pointed to research, apparently obtained and misinterpreted by the New York Times reporters and editors, demonstrating that “mass shooters were 20 times more likely to have a ‘severe’ mental illness than the general population.”

It would be a mistake to stigmatize every person with a mental illness, or to pretend that every mental condition or disability is equally dangerous — an issue that arose when the Obama administration tried to have everyone who needed help managing their disability benefits entered into the NICS database.

But some conditions really are dangerous. When Nikolas Cruz displayed self-harming behavior and threatened others, school and state officials still decided not to commit him.

A similar decision — and again, in hindsight, the wrong one — was made in the case of the Aurora, Colo., theater shooter, who murdered 12 and injured dozens of others in 2012. A psychiatrist at the University of Colorado considered placing Holmes on a mental health hold about a month before the shooting, after he shared that he was having homicidal thoughts. But she was so concerned that this move might “inflame him” that she decided against it.

As Duwe and Rocque point out, mass shooting prevention is not just a problem of mental health — it’s also about guns, without which no mass shooting can occur. But in numerical terms, the issue is mostly about keeping guns out of the hands of people with severe and dangerous mental illnesses. There’s surely room for improvement here, as Parkland, Aurora, and other cases demonstrate.

***

Mass shootings are, unfortunately, part of life. And although they are rarer in countries with less of a culture of private gun ownership, they occur even there — in Paris, in Oslo, in Paris, in Munich, et cetera — and are no less tragic. So, there’s no quick fix that can reduce such shootings to zero in the U.S., where there are more privately-owned guns than there are people.

But there are solutions with the potential to reduce mass shootings. There are other solutions that lack such potential. The gun control movement seems determined to stick with the latter. There’s no reason to think their usual go-to answer in such situations, a ban on selling “assault weapons” or even just the AR-15, would do anything.

Other proposals, such as universal background checks, might be prudent for the future, but with the caveat that this wouldn’t have saved any lives in recent mass shootings.

On the other hand, there are a number of bipartisan proposals which both gun control and gun rights advocates can sincerely get behind, and which really will make a difference. Between simply fixing the instant-check database and re-examining how professionals are trained to handle dangerous mental illnesses, we know of at least 97 mass-shooting fatalities that could have been prevented since 2007.

To most Americans, the idea that even this much could be done about mass shootings without infringing gun rights is probably almost as counterintuitive as the idea that gun violence has dramatically decreased over the last 25 years. It always feels good to spread good news.