LOUDOUN COUNTY, Virginia — For Carri Michon and Cheryl Onderchain, most of their “new normal” has involved wrestling with their local school board.

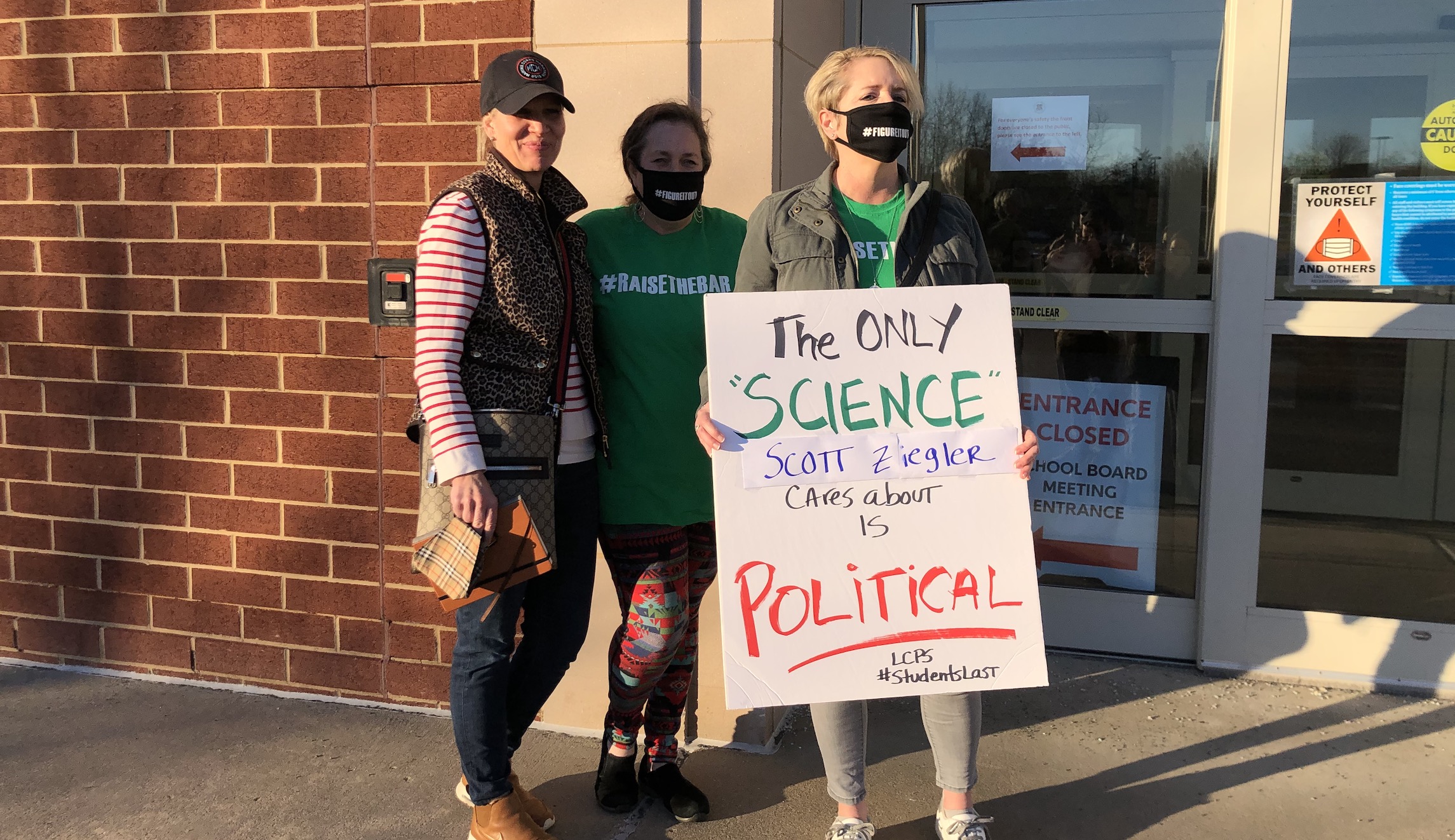

The Virginia mothers have been religiously showing up in person to the Loudoun County School Board meetings since last summer, advocating for the full reopening of in-person learning for students despite the coronavirus pandemic.

“We’re the voice of many, many, many people because somebody has to fight for the children,” Michon told the Washington Examiner at one of the meetings.

Loudoun County sits about 40 minutes outside of Washington, D.C., and is one of the wealthiest counties in the country, with a median household income of over $142,000. It has just begun sending students back to school part-time by using a hybrid model, in which students spend part of the week in class and the rest learning remotely.

Almost 15,000 students, ranging from preschool to fifth grade, whose families chose hybrid learning in a November 2020 survey, were welcomed back to attend school in person twice a week. More than 2,000 teachers also returned to classrooms, according to data from Loudoun County Public Schools shared with the Washington Examiner.

CHICAGO PARENTS AT BREAKING POINT AS TEACHERS THREATEN STRIKE RATHER THAN RETURN TO CLASS

On Wednesday, LCPS plans to welcome almost 7,000 middle school students and more than 8,000 high school students to hybrid learning, as well as more than 1,500 teachers.

But the vast majority of the more than 80,000 students enrolled in Loudoun County Public Schools have been online since the onset of the coronavirus, more than a year ago. Onderchain argues that much of the direction about what the schools’ reopening plan looks like has been unclear, and parents haven’t had much of a say over the past year.

“They sit up there with their chairs on their phones, and they don’t even look up. It’s a slap in the face,” Onderchain said of the school board members.

Like many parents across the country pushing to get their children back in the classroom, Onderchain said her focus is broader than just her two twin high school daughters, who she says have had an easier time adjusting to virtual learning because of their age and independence.

“We’re here for all the children of Loudoun, not just for our own children,” Onderchain said. “The kids who need this the most, they don’t have parents who are involved as we are.”

Loudoun County made national headlines after a local parent’s tirade against the school board, in which he said it was “more inefficient than the DMV,” went viral.

Brandon Michon, the father of a 5-year-old kindergartner who went viral in the video, told the Washington Examiner he’s heard words of gratitude from parents across the nation who couldn’t speak up themselves.

“What I think is a lot of people are frustrated that they have children who are in a situation that is not ideal for them, and I was a sounding board for a lot of parents as to why kids should be back in school,” Michon said.

In the year since full, in-person learning came to a close in Loudoun County, some parents have decided that the lack of social interaction is too damaging to wait for classes to get back to normal. For Abby Platt, withdrawing her children from the public school system was a no-brainer.

Platt — who has a kindergartner, a fourth grader, and a seventh grader — told the Washington Examiner it was the mental health toll she saw on her children, particularly her youngest, that pushed her to make the decision.

“What happened to us was devastating,” Platt said while choking back tears. “And we are the exception, my children are fine now, but what we went through was horrible.”

She, like Onderchain, was at the meetings not just because of her children but also those of other parents who are less fortunate than she is.

“What about all of these other kids that don’t have access to what we have? Who speaks for these kids? They don’t have a union that is backed by millions of dollars that is fighting for them,” Platt said.

Dr. Randall Hollister, the headmaster of Loudoun Country Day School, told the Washington Examiner that since the pandemic began, he has seen a “record amount” of applications from parents trying to enroll their children in the private school.

“Last summer was extremely busy, and we ended up enrolling the largest number of new students in our history. And we’re experiencing the same right now with the admissions process,” he said.

Wayde Byard, the public information officer for LCPS, said the district had about 4,000 fewer students than its projected number at the beginning of the 2020-2021 school year, but drop-offs since that time have been scarce.

Hollister attributes some of the record growth for his private school to the “awareness of the effective job” that his school has done at making classrooms safe, however, people are “very much yearning for a five-day in-person experience for their children.”

Foxcroft School, an all-girls boarding and day school in Loudoun County, has also seen a surge in inquiries from parents, according to Cathy McGehee, the head of the school.

McGehee told the Washington Examiner that her school has had in-person learning since the fall. She pointed out that virtual learning is no substitute for the experience of interacting with peers and teachers inside a physical classroom.

“We may not fully understand the toll of the pandemic and virtual learning on our students for years to come,” she said in a statement, adding that teenagers “learn best in community, and their education must be focused on the whole child: mind, body, and spirit.”

The “mind” is a major concern for researchers and parents.

Scott Radtke, chief clinical officer of Wisconsin-based Catalpa Health, which focuses on the mental well-being of youth, said he’s seen an uptick in people inquiring about services since the start of the pandemic and that it’s common for some parents to have trouble finding a provider for younger children.

“Not all providers may work with kids that young,” Radtke said. “I would say, in general, the demand for mental health services at times is much more than what the workforce can provide, so there are times that it is harder to find those services.”

Upon seeing the ramifications school closures were having on her kindergartner, Platt said she tried to get help, but couldn’t find anyone to take on the need, pushing her to make the choice to enroll him in a school where he could get more in-person social interaction.

“It’s my 5-year-old that broke,” Platt said, with tears in her eyes. “It’s my 5-year-old that was, like, spiraling out of control. And I called therapist, after therapist, after therapist. Dozens.”

Carri Michon said isolation is a big problem in the pandemic, and she thinks not enough is being said about students who have taken their own lives since last spring.

In Chicago, a mother is in the midst of a lawsuit with Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker after her son died by suicide to what she blames were the hardships of isolation due to the lockdowns and school closures, prompted by the pandemic.

In Las Vegas, a string of 18 suicides by students last year pushed Clark County School District, the fifth-largest in the country, to bring students back to classrooms as quickly as possible, with the first wave of students returning this week.

“When we started to see the uptick in children taking their lives, we knew it wasn’t just the [COVID-19] numbers we need to look at anymore,” Jesus Jara, the Clark County superintendent, told the New York Times. “We have to find a way to put our hands on our kids, to see them, to look at them. They’ve got to start seeing some movement, some hope.”

Michon, a mother and grandmother to children ranging from elementary school age to high school age, said she doesn’t want to see her own district mirror what happened out West.

“It’s not just the teenagers. There are elementary kids that are speaking in terrible ways,” Michon said. “It’s almost more important than the academics to me. There’s no recovery from suicide. There’s no second chance on that, and we need to be addressing that.”

Radtke said schools can often help mental health professionals find out gaps or issues a child may face, and the absence of having that kind of mandatory reporting can affect children who may be in an unstable or abusive household.

But overall isolation can negatively affect the development of a lot of children, and it’s unclear what long-term mental health issues socially distancing may have on them.

“I do believe that connection is important, especially during the development with the child,” Radtke said. “A kid only has one opportunity to be a fourth grader. One opportunity to be a fifth grader. In the life of that child to have a period of time where they don’t have that same ability to connect, that can bring some challenges for some kids.”

Even though Platt took her children out of LCPS for the time being, she continues to attend school board meetings to push for reopenings, hoping no other parent has to see their child go through what hers did.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“I have to show up because I think, ‘Who’s speaking for anyone else, no one else is speaking for these babies?'” Platt asked. “And, I do, ultimately hope that my children can go back to their school.”