On a warm spring night in Dallas, nearly 50,000 fans were already inside AT&T Stadium when the announcement went out: the show was off.

Julion Alvarez, one of Mexico’s most popular regional music stars, would not be taking the stage. His U.S. visa had been revoked without warning, just hours before the concert was scheduled to begin.

In a video posted to Instagram, Alvarez apologized directly to fans. “It is not possible for us to go to the United States and fulfill our show promise with all of you,” he said. “It’s a situation that is out of our hands. I apologize to all of you, and if God permits, we will be in touch to provide more information.”

For ticket holders, the cancellation appeared sudden and confusing. For the Trump administration, it reflected an enforcement strategy that has increasingly placed Latin American entertainers under scrutiny as part of a broader campaign to dismantle cartel networks by targeting not just traffickers, but the ecosystems that sustain them.

Over the course of 2025, the administration expanded its use of Treasury Department sanctions and State Department visa revocations against musicians, DJs, and concert promoters accused of laundering cartel money, glorifying drug kingpins, or otherwise assisting transnational criminal organizations. The actions disrupted major tours, froze assets, and forced a recalculation across a regional music industry long intertwined with cartel culture.

Administration officials argue the effort rests on a straightforward premise: cartel operations do not end at trafficking routes or bank accounts. In their view, entertainment is one of many cash-heavy industries cartels exploit to generate revenue, move money, and reinforce influence.

A Treasury Department spokesperson told the Washington Examiner that since President Donald Trump returned to office, the department has taken “dozens of sanctions and other actions” aimed at dismantling cartel finances across multiple sectors.

“Since President Trump resumed office, in addition to disrupting narcotics and human smuggling operations, Treasury has strategically targeted diverse cartel revenue streams and money laundering vehicles,” the spokesperson said. “This has so far included individuals and entities exploiting the gambling, fuel and oil, tourism, entertainment and nightlife, agricultural, and other industries.”

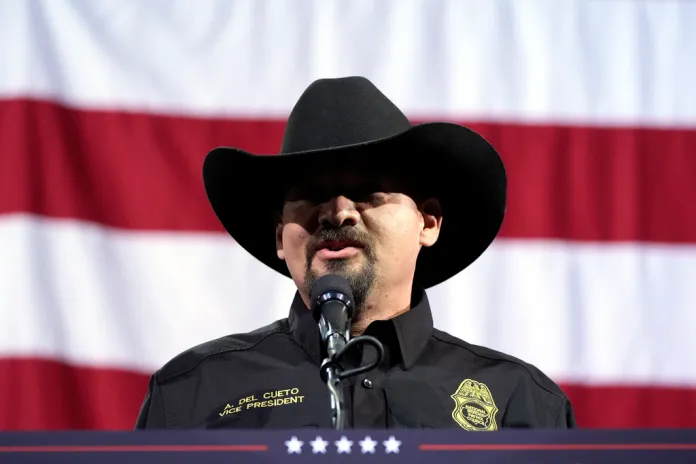

Former Border Patrol agent and close Trump ally Art Del Cueto said the administration’s approach reflects a long-standing reality along the border: that music and cartel culture have been intertwined for decades, often with financial backing from criminal groups.

“It’s almost like gangster rap,” Del Cueto told the Washington Examiner. “You’ve got illicit groups that invest in some of these artists, and the artists in turn make corridos to honor drug traffickers. That’s been going on for years. This isn’t new.”

Del Cueto, a 21-year veteran of the U.S. Border Patrol and now a border security adviser for the Federation for American Immigration Reform, said concerts and tours have historically served as vehicles not just for propaganda but for laundering money and legitimizing cartel figures.

“I think this crackdown is also a way to tell them, ‘You’ve got to show where your original money came from,’” he said. “If these artists are being funded by narco groups, then it’s fair to start asking where that money is coming from.”

Visa revocations reach the stage

The most visible actions came through visa revocations, a discretionary tool the administration increasingly deployed against high-profile performers.

In March, the members of the norteño band Los Alegres del Barranco had their U.S. visas revoked after projecting an image of Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera, the leader of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, during a concert in Guadalajara. Video of the performance circulated widely online.

Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau confirmed the revocation publicly, writing on X that the band had glorified a cartel leader now designated by Washington as a terrorist. “I’m a firm believer in freedom of expression,” Landau wrote, “but that doesn’t mean expression should be free of consequences.”

I’m a firm believer in freedom of expression, but that doesn’t mean that expression should be free of consequences. A Mexican band, “Los Alegres del Barranco,” portrayed images glorifying drug kingpin “El Mencho” — head of the grotesquely violent CJNG cartel — at a recent concert… pic.twitter.com/neSIib7EC4

— Christopher Landau (@DeputySecState) April 2, 2025

Landau emphasized that entry into the United States is a privilege tied to national-interest determinations. The decision effectively canceled the band’s American tour. Los Alegres later issued an apology, saying the imagery was not intended to glorify criminal organizations, but the visas remain revoked.

Weeks later, Grupo Firme, one of the most commercially successful acts in regional Mexican music, announced it had canceled a U.S. festival appearance after its members’ visas were placed under administrative review. “At this moment, the visas of Grupo Firme and the Music VIP team are under administrative process by the U.S. Embassy,” the band said in a statement.

Del Cueto said visa revocations are a legally clean response to performers who glorify or associate with cartel figures, noting that foreign artists have no inherent right to enter the U.S.

“This isn’t a First Amendment issue,” he said. “These are not U.S. citizens. They don’t have a right to come here and promote an ideology or a lifestyle tied to criminal organizations. Entry into the U.S. is a privilege.”

The visa actions coincided with renewed pressure inside Mexico. President Claudia Sheinbaum criticized onstage glorification of cartel leaders, saying after the Los Alegres incident, “That shouldn’t happen. You can’t make apologies for criminal groups.”

Julion Alvarez and the weight of history

Alvarez’s case carried particular weight because it was not his first encounter with U.S. enforcement.

In 2017, during the first Trump administration, the Treasury Department sanctioned Alvarez under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, accusing him at the time of acting as a front man for cartel figures. Alvarez denied the allegations, and in 2022 — under the Biden administration — U.S. authorities lifted the sanctions and restored his travel privileges.

This year, those privileges were revoked again.

The State Department has declined to comment on the specific reason for the decision, citing confidentiality rules governing visa records. Promoters said the stage in Dallas had already been constructed and crews were preparing when the decision came down.

Alvarez told fans the decision blindsided his team. “We had everything ready,” he said. “This is not something we wanted, and it’s not something we control.”

Other performers encountered similar disruptions. Singer Luis R. Conriquez, whose cartel-themed lyrics have drawn scrutiny from Mexican authorities, faced visa complications after officials ordered him to stop performing certain songs mid-concert earlier this year. Younger artists, including Tito Double P and Natanael Cano, also saw U.S. visas revoked or questioned, in some cases over technical violations unrelated to cartel allegations.

Treasury targets the money and criminals — far beyond music

While visa revocations drew the most public attention, Treasury sanctions carried longer-term financial consequences — and increasingly extended beyond performers themselves to the revenue streams surrounding them.

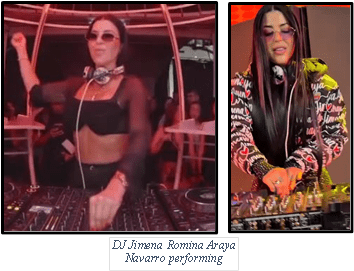

In December, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctioned Venezuelan entertainer Jimena Romina Araya Navarro, known professionally as Rosita, accusing her of laundering money for the Tren de Aragua gang. Treasury alleged that proceeds from nightclub performances were routed to gang leadership and that venues associated with her appearances were used to facilitate narcotics sales.

Officials described the case as emblematic of how criminal organizations exploit entertainment and nightlife to move illicit funds — a pattern Treasury says is not confined to any single industry. Weeks later, the Justice Department announced an indictment for Araya Navarro, who is alleged to have taken part in a scheme along with 53 others of deploying malware to steal millions of dollars from ATMs in the U.S., a crime commonly referred to as “ATM jackpotting.”

“Jimena Romina Araya Navarro has been publicly photographed at parties and social events with the alleged head of TdA Nino Guerrero,” the DOJ said in a press release on Dec. 18.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has framed the department’s enforcement posture as deliberately expansive, aimed at cutting off cartel revenue wherever it surfaces.

“President Trump made a promise to pursue the total elimination of drug cartels to protect the American people,” Bessent said in a recent sanctions announcement. “No matter where or how the cartels are making and laundering money, we will find it and we will stop it.”

Consistent with that approach, Treasury and its Financial Crimes Enforcement Network have issued sanctions, findings, and alerts this year targeting cartel-linked operations in fuel and oil theft, gambling, tourism, agriculture, and cross-border financial networks tied to groups such as the Sinaloa cartel.

Concerts as cash pipelines

The administration’s focus on entertainers builds on earlier law-enforcement findings that concerts and tours can serve as effective vehicles for laundering illicit funds.

In 2018, Treasury sanctioned Mexican concert promoter Jesus “Chucho” Perez Alvear, alleging he laundered cartel money through music events. That case culminated this year with one of the most significant prosecutions to date involving the U.S. music industry.

In August, a federal judge sentenced Jose Angel del Villar, the CEO of Del Records and Del Entertainment Inc., to 48 months in federal prison for conspiring to violate the Kingpin Act by continuing to do business with Perez after he was sanctioned. A jury convicted del Villar in March on one count of conspiracy and 10 counts of violating the statute.

Del Villar, who according to the DOJ did business with Chucho, was also ordered to pay a $2 million fine, while Del Entertainment received three years of probation and a $1.8 million fine, according to the department.

Prosecutors described the conduct as “a sophisticated criminal scheme sustained over a lengthy period of time and involving myriad unlawful transactions,” charging the case under the Justice Department’s Operation Take Back America initiative.

What changed under Biden — and what didn’t

During the Biden administration, the U.S. also relied on sanctions and indictments to combat drug trafficking. In December 2021, then-President Joe Biden signed Executive Order 14059, authorizing broad sanctions against foreign persons involved in the global illicit drug trade.

That authority was used to target cartel leaders, fentanyl trafficking networks, and financial facilitators. But there is no public record of the Biden administration revoking visas or sanctioning entertainers or cultural figures on allegations of cartel support or glorification.

The current Trump administration has taken a more expansive view of cartel infrastructure, extending enforcement tools into sectors previous administrations largely avoided.

Terror designations expand the toolset

That shift accelerated in February, when the Trump administration designated major cartels — including the Jalisco New Generation Cartel and the Sinaloa cartel — as foreign terrorist organizations.

TRUMP SANCTIONS VENEZUELAN MODEL OVER ALLEGED SUPPORT FOR TREN DE ARAGUA

Treasury officials argue cartels rely on diversified ecosystems extending beyond narcotics trafficking, embedding themselves in entertainment, nightlife, fuel markets, and other cash-intensive industries.

“Since President Trump resumed office, in addition to disrupting narcotics and human smuggling operations, Treasury has strategically targeted diverse cartel revenue streams and money laundering vehicles,” a Treasury Department spokesperson told the Washington Examiner. “No matter where or how the cartels are making and laundering money, we will find it and we will stop it.”