The wonkier parts of political media world spend a lot of time thinking and writing about how candidates win—what mix of positions fits a specific district or state, which candidates have demographic paths to victory and which don’t, how the math looks in a midterm versus a presidential year, etc. And political audiences seem to appreciate that—everyone wants to read stories about how their preferred candidate or party might end up winning in the next election.

But sometimes it’s worth thinking about how to lose—or at least how to turn a race that should be uncompetitive into a competitive one. Looking at these races can give us a window into what voters really love or hate—that is, the sort of stuff that makes people leave their partisan attachments or past voting patterns at home and cast their ballot, out of disgust or desperation, for someone else.

So far, not many Senate races fit that description. After the 2016 election, we had a pretty solid grasp of which states would be competitive, and that picture hasn’t changed much since then. And I plan to cover House districts that fit this pattern in a somewhat different way.

But there are some gubernatorial races that fit the bill. We’ll start with the Republicans.

Spotting Underperformers

But a couple gubernatorial races fit that pattern. I’ll start by talking through the GOP side then I’ll move to the Democrats.

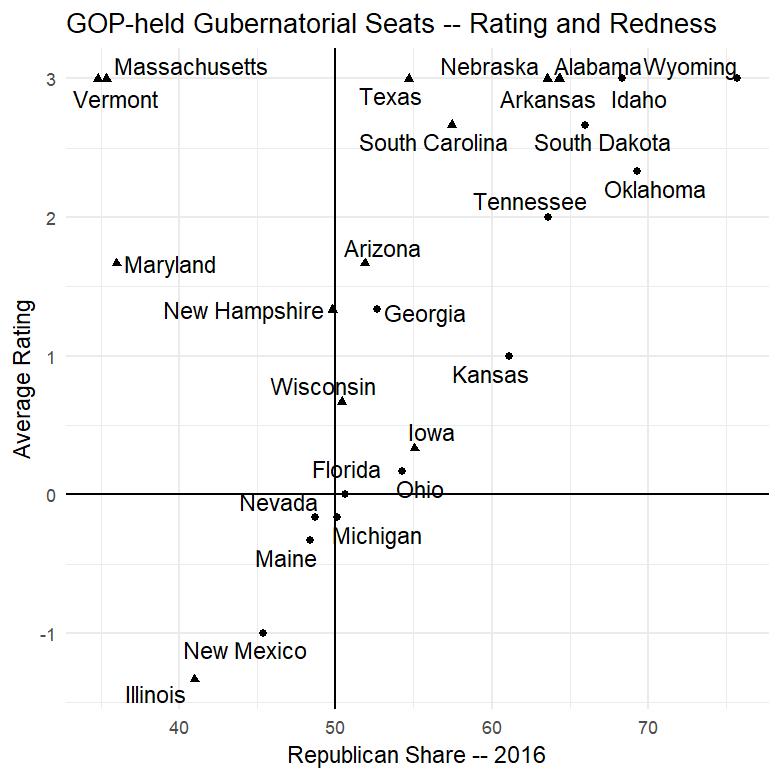

This scatter plot shows Trump’s share of the two-party vote in 2016 in each state (horizontal position) and the “average rating” (this is the average race rating from Sabato’s Crystal Ball, Inside Elections, and Cook Political Report with “Safe Republican” translating to 3, “Likely Republican” as 2, “Leans Republican” as 1, Toss-up as 0, etc.) for each state’s gubernatorial contest (vertical position). The triangles are states where an incumbent is running and the circles represent open seats.

There are a few major clusters. In the upper-right corner there are red states that Republicans should hold easily. In the upper left hand side, there are races where popular Republicans are running strongly in highly blue states (Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maryland). The middle of the graphic features swing and Republican-leaning states where the contest is either close or slightly tilted towards the GOP.

Two states fail to fall into these categories—Kansas and Illinois. And both serve as cautionary tales to Republicans everywhere.

Kansas: Nominate a Terrible Candidate After an Unpopular Administration

In 2016, Kansas voted for Donald Trump by a whopping 20-point margin. Every other state that’s that red is in the upper left-hand corner—the “Likely” or “Solid” Republican zone. But Kansas only “Leans” Republican based on our average measure. So what happened in Kansas?

First, former Republican Gov. Sam Brownback ended his tenure at a very low point. Brownback (who was first elected in 2010 then re-elected in 2014) cut taxes hugely. That’s not a surprising move: Republicans generally believe in smaller government and often try to cut taxes. But Brownback’s cuts didn’t go well. Kansas ended up with budget shortfalls and less economic growth than what Brownback might have hoped. At the end of his tenure (he left Kansas to become the “ambassador for religious freedom”), He had a 24 percent approval rating according to Morning Consult.

Then Republicans nominated Kris Kobach for the seat. You might have heard of Kobach . He was the vice chairman of Trump’s Commission on Election Integrity —basically a committee created to try to justify Trump’s baseless claim that 3 million to 5 million illegal votes were cast and that that cost him the popular vote. Kobach is also an immigration hardliner (he helped craft Arizona’s controversial S.B. 1070 law) who has been held in contempt of court and has serious baggage from his radio show.

Kansas shouldn’t be this much of a problem for Republicans. It’s a red state, and any candidate who can unite moderate and conservative Republicans (both exist in Kansas) should be able to win elections relatively easily. But there’s a saying (often incorrectly attributed to former Democratic Gov. Kathleen Sebelius) in Kansas politics—that “Democrats don’t win the state so much as Republicans lose.”

And Kobach, especially in a post-Brownback era, is in more danger of losing than a generic Republican might be. He’s still favored according to the handicappers —partially because Kansas is highly red state, and partially because Greg Orman (an Independent candidate) has entered the race. Orman may grab moderates that Democrat Laura Kelly would have otherwise won, allowing Kobach to win with a plurality.

Whether Kobach ends up winning or not, the message of this election is clear: It’s best not to nominate candidates with loads of baggage, and don’t pass laws that both cause large budget shortfalls and fail to produce sufficient growth.

Illinois: Alienate the Base and Swing Voters

Bruce Rauner might seem like an odd fit in this list. He’s the governor of Illinois, one of the most reliably blue states, so it might not be clear that this race was “winnable” in the first place.

But other incumbent Republicans in bluer states—like Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan and Vermont Gov. Phil Scott—seem to be in good shape despite governing states that are arguably bluer than Illinois. So why not Rauner?

The answer is pretty simple—Rauner has managed to alienate his base without winning over skeptical voters from the other side.

Rauner, like other blue state Republicans, originally promised not to do much on social issues. But he went back on that promise and expanded taxpayer subsidized abortions. That led to an almost-successful primary challenge—state legislator Jeanne Ives finished just three percentage points behind Rauner in the state’s Republican primary.

Other blue state Republicans make up for these transgressions by governing competently. That’s arguably what happened to Phil Scott, who managed to win renomination in Vermont by a solid margin despite losing some support over his a gun control bill. But Rauner had serious issues with the state budget. As a result, his overall approval rating in the most recent Morning Consult poll was only 27 percent—making him the least popular incumbent governor running for re-election.

Connecticut: Just Keep The Recession Rolling

Democrats aren’t defending many governorships this fall. But they have one that fits the bill: Connecticut.

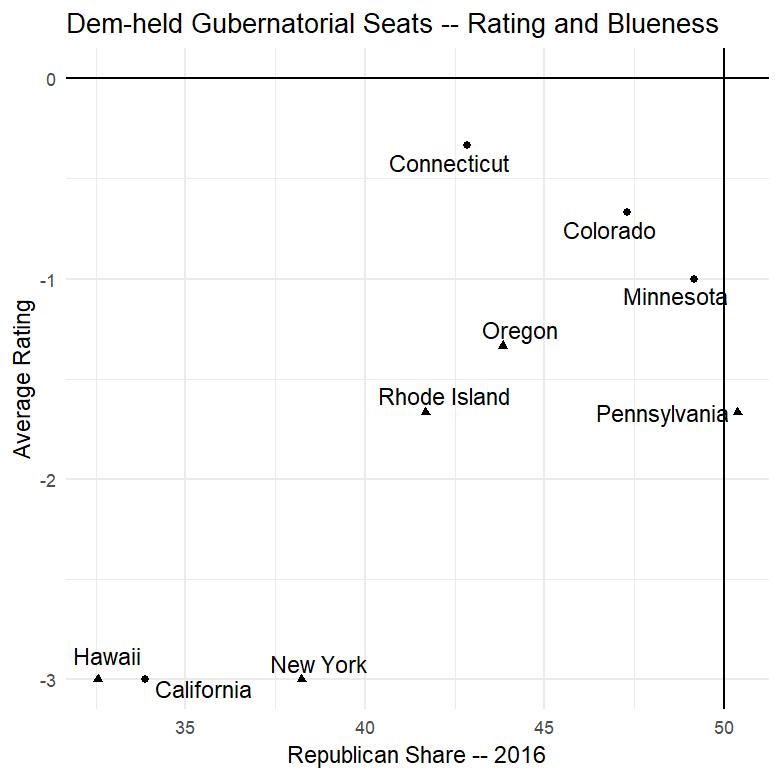

This is the same graphic as the one shown above, but it shows Democratically held states rather than Republican states.

And one point stands out: Connecticut.

Connecticut, despite being about as blue as Rhode Island or Oregon, is reasonably competitive. That seems to be mostly because the state’s economy.

Dannel Malloy, the Democratic governor, narrowly won the governorship in 2010 and won again by only three points in 2014. Malloy took over while the state was still recovering from the recession, but the state hasn’t recovered under his tenure. According to the state Labor Department, Connecticut is one of the only states that hasn’t recovered all the jobs it lost during the Great Recession.

Moreover, Malloy (like Brownback) got the worst of both worlds on economic policy. Malloy raised taxes, but it wasn’t enough to fix the state’s budget shortfall. And major businesses like General Electric moved out of the state – leaving Connecticut with a tough economic situation and budgetary issues.

Malloy has declined to run for a third term, and Republican Bob Stefanowski will face off against Democrat Ned Lamont in the general election. But Malloy casts a long shadow, and his inability to solve the state’s fiscal problems are making a blue state in a Democratic year reasonably competitive.

Connecticut, like Kansas, shouldn’t be competitive—especially in an anti-Trump, pro-Democratic political environment like this one. So the moral is simple: if you spend eight years in office and the key economic problems haven’t been fixed, your party might have issues the next time around.