Because of its history and geographical location, Oberlin College has had a long and important history in the American civil rights movement. In 1835, it was the first college to establish a policy of admitting African-American students, and two years later, the first American college to admit women to its baccalaureate program. In 1858, more than 30 Oberlin students and townspeople invaded a city nearby and freed a male slave held in captivity and destined to be returned to his owners in Kentucky.

It was a key northern junction point on the Underground Railroad, being 15 miles from Lake Erie and the freedom boats that would ferry the escaped slaves to Canada. A few blocks away a large statue of Martin Luther King Jr. celebrates his many speeches to students in Oberlin, the first in 1957.

We could go on and on. Not surprisingly, these days the college has lots of anti-frackers, socialists, gender activists, and social justice warriors banging the drum to keep entitlements from getting cut. Oberlin College’s unofficial slogan says it all: “We put the liberal in liberal arts.”

The latest civil rights kerfuffle at Oberlin is a seemingly minor issue, but the fact it has been going on for two years tells you a great deal about life at small liberal arts colleges in the 21st century.

A day after the 2016 election, an African American student attempted to shoplift wine from a local bakery/convenience store, and he and his two companions fought with the shop owner as he tried to catch them fleeing. The police report of the incident found nothing too unusual. Shoplifting occurred, the one stealing tussled with the store owner Allyn Gibson inside and then outside, and then arrests were made when police arrived. The officers reported that Gibson “had several abrasions and minor injuries; including what appeared to be a swollen lip, abrasions to his arm and wrists and a small cut on his neck.”

And yet, Allyn Gibson was seen as the perpetrator here, not the victim. More than 100 students protested outside the store after arrests, and a school administrator passed out leaflets saying Gibson’s Bakery was racist, according to witnesses at the protest. Further, the school proposed to businesses in the

to agree to call the school and not police if students were caught shoplifting in their stores in the future. The school would give each student a “free pass” for their first theft.

Gibson’s became so frustrated that the owners sued Oberlin College about a year ago, claiming that the school’s response to the shoplifting has caused irreparable damage to their business.

It raises an interesting legal question: By supporting its students’ protests of perceived civil rights problems with an existing business—and suggesting that the businesses lighten up when theft occurs—is Oberlin College violating the rights of that business? The lawsuit says the school has hurt the business, and that the school is trying to satisfy its more liberal students and alums just like a business would do in its marketing program; that is, making the school appeal to students and parents with more leftist leanings.

“Oberlin College took a position that sacrificed the commitment to the rule of law and safety of the Oberlin Community in favor of its desire to promote the business and marketing plan and public relations image of Oberlin College,” the lawsuit states. “In so doing, Oberlin College by example, words, and conduct exploited its students and taught them that it is permissible to harm community members without repercussions.”

Some may think that Gibson’s may be overreacting. But privately, one family member at the store acknowledged that their revenues have dropped “by a huge amount” since the shoplifting and subsequent protests. Other business leaders in the downtown area said that some administrators and students continue the accusations that Gibson” is “racist,” but offering no real proof it is now or has been since the business opened more than 100 years ago.

The only proof offered for racism against students is that Gibson’s and other businesses is that many make students leave their backpacks at the front of the store when shopping, because some backpacks in the past have tended to fill up with stolen items if the students were allowed to carry them while shopping. Stores near all universities seem to understand that.

Krista Long, owner of a Ben Franklin’s store on the town square near Gibson’s, told a student publication last year she was losing about $10,000 a year in shoplifting theft. “Theft is demoralizing to us,” she said, “making us feel that we should suspect the very customers we want to serve.”

That sentiment has not penetrated the students’ mindset much. Oberlin College student Sophie Jones, editor-in-chief of The Grape, a student publication, wrote an opinion piece called “This Is Not a Call to Action: I’m Coming Out” that came out in September.

The lawsuit is set to go to trial in the spring. Neither the school nor its lawyers returned requests to comment for this story. The Ohio attorney for Gibson’s, Lee Plakas, was also reluctant to comment on the lawsuit, but did offer this thought on the seriousness of the case in the social political and cultural dystopia now at play.

“Sometimes attitudes and actions of powerful institutions that spawn cases like this continue until the full array of personal and economic consequences of defamation are recognized,” Plakas said. “Until recent national events, some say that our society and its powerful institutions have been slow to recognize the toll extracted by defamation. It has been said the damages from defamatory statements are difficult and costly to repair – you can’t ‘un-ring the bell.’ “

***

After the first student protests against Gibson’s happened, there was some national news coverage of the events. Most were of the “here the liberal college students go again” variety, and most missed the biggest factor at play in the protests: the Trump election.

The dates are key: the Trump/Clinton election was on Nov. 8, the shoplifting was in the afternoon of Nov. 9, and the protests started that night and continued for days after.

Eric Gaines saw the relationship between the election and the protests immediately. African-American and a longtime Oberlin resident (and who currently serves on the city’s planning commission), the retired air-traffic controller testified in a deposition filed in August that the protests he viewed “blew my mind. It was preposterous.”

“My theory is that the election occurred the night before [the shoplifting], … and Oberlin has always been ultra-liberal. So people were anxious and it was like a time bomb ready to explode,” Gaines testified. “It was a bunch of kids who were lashing out because of a national issue … [The protest] was just like throwing gasoline of a fire.”

Within a day of the incident, the Oberlin College student senate passed a resolution ceasing all support for Gibson’s Bakery, financial and otherwise. The administration even weighed in in a letter dated Nov. 11, specifically mentioning how upset the college community must be about the election and offering support for student protesters.

“This has been a difficult few days for our community, not simply because of the events at Gibson’s Bakery, but because of the fears and concerns that many are feeling in response to the outcome of the presidential election. We write foremost to acknowledge the pain and sadness that many of you are experiencing,” Oberlin College President Marvin Krislov and Vice President and Dean of Students Meredith Raimondo wrote to the faculty and students.

Journalist Jason Hawk, editor of the Oberlin News Tribune had some interesting observations. He was at the protest to take photos and interview people there, as any journalists would do. He was forced to give a deposition in the case by a court ruling.

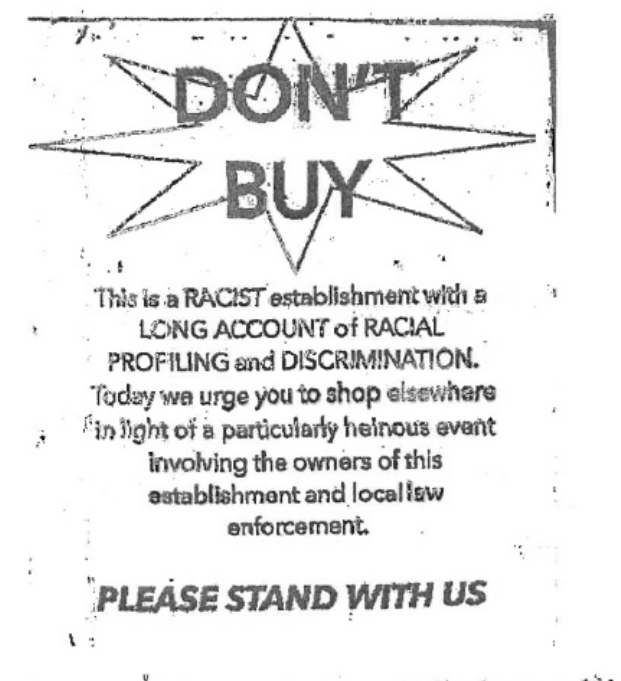

Raimondo, the dean of students, stood in front of him and blocked his ability to take photos, Hawk said in the deposition. “She argued we didn’t have the right to take photos of the protest,” he told the court. Raimondo, he said, was also handing out flyers “that insinuated that Gibson’s Bakery was a racist institution.”

The flyers in question said, in part, “This is a RACIST establishment with a LONG ACCOUNT of RACIAL PROFILING and DISCRIMINATION.”(caps on flyer).

Oberlin College’s response to the lawsuit is that the school is the victim in all this. “By filing this lawsuit, [Gibson’s Bakery] regrettably are attempting to profit from a divisive and polarizing event that impacted Oberlin College (“the College”), its students, and the Oberlin community.”

That this lawsuit is still going on two years after the incident has many questioning whether Oberlin College has its legal head on right. “Once the guilty plea of the shoplifter was done, you’d think Oberlin College would have smoothed things out and settled but they haven’t,” says William Jacobson, a professor at Cornell Law School and author of the Legal Insurrection blog.

“The school is going after an old town institution, saying the media is against them and trying to get the venue changed, and trying to defend a protest by social justice warrior students that has no real reason really to be done in the first place,” Jacobson said. “This is very unusual … I’ve never seen a towns-and-gowns divide like this.”

Robert Piron, an Oberlin College professor emeritus of economic agrees. He also was deposed for the lawsuit and had some startling observations of the institution where he actively taught from 1961- 2007.

“I reached the conclusion that that if you could say [Oberlin College] had a mind, it is certainly out of its mind by now. It was the dumbest thing I have seen in years.”

“As far as I am concerned, they are scandalously hurting the Gibson’s continually,” Piron continued. “It’s astoundingly cruel and dumb of the college. And I don’t think I will ever forgive them. I’m furious, absolutely furious.”

***

How this all sorts out will mostly likely happen during 2019. Oberlin College had tried to move the case to the more liberal Cuyahoga County (with Cleveland as the county seat) because “the media coverage within Lorain County of this case and the events giving rise to it has been sensationalized and has not been accurate or impartial.” They cited an online comment on one story that said “I hope Gibsons wins this lawsuit” as proof of the lack of impartiality. The judge quashed the venue change request.

But Lorain County is interesting and worthy of discussion because of its changing political leanings. During the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, Lorain County voted for Obama 58 percent to 40 percent. But in 2016, Clinton won by only about 130 votes out of roughly 134,000 cast in that county.

The city of Oberlin, by contrast, voted for Clinton by about 4600-450 in 2016. And to see how dominated Oberlin is by the college, the city has a population of 8,000, with 3,000 of those students and about 1,000 school employees. It is Democratic bubble of sorts in a part of the country that is more Republican than it ever really used to be.

What’s odd is that this dispute between a small business and a self-described liberal college has not caught the interest of the left or the right. Among either pundits or politicians.

Oberlin is represented in Congress by Republican Jim Jordan, and many in the town think their congressmen has ignored them. “The only time I see Jim Jordan is on TV, when he’s saying Donald Trump’s a great man,” Oberlin city councilman Ronnie Rimbert said in an interview last year. “Jim could care less about what’s going on in Oberlin because he knows what our voter strength is, and it’s definitely not going his way.”

Jordan disagrees. His spokesman says he has visited Gibson’s Bakery and appeared on a local Cleveland radio program discussing the Oberlin case. But in all fairness, I couldn’t find anyone who remembered such a visit or find any media coverage of it.

“He visited the bakery and expressed solidarity and has done what he can to help them,” Jordan spokesman Ian Fury said. The Democratic candidate for Jordan’s district, Oberlin resident Janet Garrett, a retired public school teacher, wouldn’t talk about the Gibson case to THE WEEKLY STANDARD because “we’re swamped right now with Kavanaugh stuff” according to her spokesman.

Same goes for Republicans John Kasich, the governor, and Rob Portman, senator. Across the aisle, Senator Sherrod Brown and Marcia Fudge, whose district is just east of Oberlin, also have been silent on the issue.

“I think the politicians don’t see much of an angle of benefit on either side of this,” Cornell’s Jacobson says. “On the one hand it is probably seen nationally as just another strange thing coming out of Oberlin. But also, the media and politicians and the activists from either side can’t seem to get their hands around anything that isn’t coming out of D.C. these days.”

But there may be a larger issue at play: Small, private, liberal arts colleges are having a hard time figuring out who they are any more. Like many Midwestern private schools, Oberlin was founded in the 1800s as an isolated, intellectual alternative to the Ivy League schools back east. They were able to pick and choose their enrollment demographics, getting to be as racially and economically balanced as they wanted to be, religiously varied as well, and get students from most of the 50 states and many foreign countries, too.

That was the attraction. A culturally diverse, small college with open debate. And away from New York and Boston and Philadelphia.

It is not really that way anymore. Oberlin College is now 73 percent white-American, 9 percent foreign-born, 8 percent Hispanic-American, 6 percent African-American and 4 percent Asian-American. The cheaper public schools are generally more ethnically diverse, have more working-class students, and without any of pretend isolation that Oberlin College still uses as a marketing tool.

And so the political affiliations of the private liberal arts faculty seem to be extremely out of whack with the general public’s political affiliations. In April, Mitchell Langbert, an associate professor of business at Brooklyn College, published a study of the political voting registrations of the faculty at 51 of the top-ranked liberal art colleges. Oberlin College was included.

He found, not surprisingly, that most of the college professors were far more Democratic than Republican. He examined 196 professors at Oberlin College, with 109 registered as Democrats and seven as Republicans (45 were not registered to vote, and 35 were registered, but with no party designation).

Does this obvious party leaning have anything to do with how the school has dealt with the Gibson case? The answer is yes and no.

“Yes, the liberal bent at schools like Oberlin has them thinking a certain way, and not with the public generally, but it has sort of always been that way,” says a former Oberlin College administrator who is no longer at the school. “The difference now is that they don’t encourage discussion and disagreement, they want everyone to be on the same side and that is disheartening. It is about marketing because their enrollment is down.”

“What has happened in the Gibson case is that the school doesn’t know what to do with its minority students,” the former administrator continued. “A freshman from an east coast big city might come to Oberlin and find there is little for a social justice warrior to do in a small town like this, so they get frustrated. And make issues like this shoplifting thing bigger than it should be, and the school follows along.”

I thought about those comments while sitting in the town square park across from Gibson’s Bakery. A young male student walked by with a t-shirt with “Fear Eats the Soul” scrawled on it. In some ways this is normal college student expression that has always had a fear-and-loathing with isolation bent to it. But here in Oberlin, perhaps that shirt saying has more meaning when a cookie and candy maker is feared by many students to be racist.

The Oberlin College administration has been silent on the Gibson’s Bakery issue since the lawsuit was filed. Early in October, the college did inaugurate Carmen Twillie Ambar as its 15th president and first African-American. She did not mention racial issues specifically during her inauguration ceremony, but did say that a positive aspect of Oberlin College is that “we’ve been open to fairly radical change as compared to our peers.”

Ambar also wrote a letter to students in late August to be nicer to the townies. “The goal is to introduce students to the town’s many special qualities, while communicating clearly the college’s expectations for appropriate behavior on a wide range of issues, such as noise, street crossing, bike parking and shoplifting,” she wrote. “From talking with some of you, I know you believe as I do that the future of Oberlin College and the city of Oberlin are inextricably intertwined. Neither can flourish without the other.”

Has that that message gotten to the students? Perhaps. This is what student Jackson Zinn-Rowthorn wrote about the Gibson’s controversy for the Sept. 23 issue of the student-run Oberlin Review :

“As the ‘Support Gibson’s’ lawn signs sprouting up around Lorain County remind us, the Gibson’s boycott is not like the abstracted, at-a-distance activism typical of college campuses,” he wrote. “Our actions on this front have a direct and dramatic impact on the lives and livelihoods of dozens of people in the greater Oberlin community.”

“These people are not caricatures. They are not merely the sum of their worst inclinations. They are our hosts—when they push back against us, we owe them our sincere consideration. As students, we inevitably leave Oberlin behind, and with it, the repercussions of the choices we made here. But the residents of the town remain. They inherit our legacy.”