MCALLEN, Texas — It almost seemed as if the spectacle had been arranged in advance. As a group of Republican activists gathered for what organizers called “an immersive experience at the U.S.-Mexico border,” several men on the Mexican side of the bollard-style fencing separating the two countries suddenly appeared in the distance, erected a tall ladder, climbed it, went over the fence, and then jumped down and disappeared into the South Texas shrubland, while two men on the Mexican side retreated with the ladder.

Several other journalists and I had been invited to McAllen, the southern border’s most heavily trafficked migrant corridor, to join a group of conservative women lawmakers and activists in surveying the landscape that serves as ground zero in the immigration debate. But I was particularly interested in meeting the three women who are leading a movement that’s reshaping the political landscape.

Mayra Flores, Monica De La Cruz, and Cassy Garcia are running for the House of Representatives in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. These Republican Latinas have made border security a cornerstone of their campaigns, framing the threat posed by illegal immigration as an “invasion,” a humanitarian crisis, a national security threat, and even a women’s rights issue — while placing blame for the crisis squarely on the Biden administration.

“Biden is in a party that advocates for women, immigrants, children,” De La Cruz told me as we stood along the shores of the Rio Grande, where the bodies of migrants who run afoul of cartel-employed human smugglers sometimes wash up. “And to see how he has put women, children, law enforcement agents in these horrendous situations has absolutely shocked me.”

De La Cruz is running for the open seat in Texas’s newly redrawn 15th Congressional District, which runs from the Rio Grande Valley north past San Antonio. De La Cruz came within 3 points of winning the seat in 2020 against incumbent Democrat Vicente Gonzalez. And this time, after redistricting, she’s facing a political newcomer in a more GOP-friendly district.

De La Cruz grew up in a Democratic family. Flores did as well. But one day, she realized her views on abortion, faith, and immigration were more in line with those of the Republican Party. Plus she’d always felt taken for granted by the Democrats.

“In this area, Democrats never did anything to earn our support,” Flores said.

In June, Flores won a special election for the seat of a departing Democratic congressman, becoming the first Mexican-born woman in the House. Now she’s squaring off against Gonzalez, who’s running in the newly redrawn and more Democratic-friendly 34th Congressional District.

All three women grew up in the Rio Grande Valley — Flores immigrated legally to the United States when she was 6 years old — so they see the consequences of the border crisis every day. Flores and Garcia are both married to Border Patrol agents.

“My husband’s a Border Patrol agent of 26 years, serving this great country, and he’s never seen the border like this,” said Garcia, who’s running in the 28th Congressional District against longtime incumbent Rep. Henry Cuellar, a centrist Democrat.

When asked why they’re running for office, all three women articulate some version of “to defend faith, family, and freedom,” the battle cry of nearly all conservative Republicans. But immigration is their focus, and they return to it often.

When I asked Garcia which areas she’s emphasizing in her campaign besides immigration, she said, “the economy, inflation — and securing our border.”

Their fixation on the border crisis stands in contrast to the Biden administration’s neglect of it. In fiscal year 2022, the Department of Homeland Security reported a record 2.4 million immigrant encounters on the border. Every day in the Rio Grande Valley, the Border Patrol apprehends some 1,300 migrants trying illegally to enter the country.

Despite that, deportations under the Biden administration have dropped to their lowest level in the history of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In August, the Biden administration ended Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” policy, which barred most migrants from entering the U.S. to seek asylum and mandated they be sent back across the border to await the resolution of their claims.

Flores, Garcia, and De La Cruz, all young, nonwhite, and bilingual, offer Republicans an implied retort to the tired accusation that their policies, especially regarding immigration enforcement, are racist, xenophobic, and misogynistic. They are also a response to “the Squad” — the group of progressive members of Congress led by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) that’s been beguiling Democrats and bedeviling Republicans since its emergence in 2018.

And they can match the Ocasio-Cortez contingent in strident rhetoric. Flores, for instance, has called for President Joe Biden’s impeachment and labeled the Democratic Party the “greatest threat America faces.”

Allies have taken to calling the women “the triple threat” as Democrats’ longtime claim to Latino loyalty has begun to crack.

The loosening of the Democratic Party’s hold on Hispanic voters has caught many in both parties by surprise.

Ten years ago, Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) lost the Hispanic vote by 44 points in his presidential election loss to Barack Obama. During the campaign, Romney claimed that under his immigration plan, illegal immigrants would “self-deport,” a Romneyism that baffled supporters and critics alike.

After the election, the Republican National Committee’s much-discussed “autopsy” report advocated liberalizing immigration policies. “If we do not,” the report said, “our Party’s appeal will continue to shrink to its core constituencies only.”

Two years later, Donald Trump launched a presidential campaign referring to Mexican immigrants as rapists and drug dealers and promising to build a wall on the southern border. As president, Trump implemented policies that included the separation of immigrant children from their families, the expansion of physical barriers on the border, and new restrictions on asylum claims.

And yet, in 2020, Trump improved upon his 2016 performance with Hispanic voters, winning an extra 8 to 10 points (to 38%), depending on the study.

Trump’s improvement was even stronger in the Latino-dominated border counties in Arizona and Texas. Trump lost Starr County, Texas, by just 5 points in 2020 after losing it by 60 points four years earlier. And Trump won adjacent Zapata County after losing it by 33 points in 2016.

Overall, Trump won half the 28 counties on or near the Texas border that Hillary Clinton had won in 2016 and halved the Democratic margin of victory in the full tally of those 28 counties.

Some Hispanics were drawn to the GOP for its socially conservative and free market economic policies. Others supported Trump not despite his hard-line immigration stance but because of it.

Trump’s success may have birthed a generation of Hispanic Republicans, including Flores, De La Cruz, and Garcia. De La Cruz told me Trump’s no-nonsense approach to securing the border convinced her to vote for him in the 2016 presidential primaries, the first Republican she’d ever voted for. And Flores has said Trump gave Latinos permission to “no longer [be] ashamed to be conservative.”

More than that, almost all the Hispanic Republicans I met credited Trump for inspiring their political involvement and continue to embrace the MAGA platform. Yet Trump’s name seldom came up — and usually only when I raised it. Often, when I asked a question about Trump, many otherwise forthright Republicans suddenly became rather evasive.

Consider the responses when I asked Garcia, Flores, and De La Cruz separately the following question:

“Do you believe Joe Biden legitimately won the 2020 election?”

MAGA true believers still insist that Biden didn’t win, the election was stolen, and Trump should be president. And there are still many Republican candidates who publicly say this. A recent analysis estimated that 60% of voters will have an “election denier” on the ballot this fall.

But these women all seemed to acknowledge that Biden won in 2020, though not without hesitation.

Cassy Garcia: “I mean — [pause] — yeah, I do.”

Mayra Flores: “He is the worst president we ever elected. He is our president (laughter).”

Monica De La Cruz: “I think that Biden is our president now. What we need to do is look forward and not back.”

I also asked them, “Would you support another Trump run for president?”

Flores: “Look, I am now a member of Congress (chuckle), so I need to focus on Texas-34 and the midterms.”

Garcia: “Oh, you know, right now I’m just so focused on the midterms and winning this election right now. But the policies did work. The policies that came from his administration were absolutely amazing.”

It’s as if they’re saying, “Thank you for all that you’ve done, Donald. Now we’ll take things from here.”

According to local Republicans, there are three reasons why the Rio Grande Valley is trending in their direction. The feeling of being taken for granted by Democrats is one of them. Another is that in 2020, a new law ending “one punch” straight-ticket voting took effect. That forced voters to consider each candidate on a ballot, instead of choosing a party’s entire slate of candidates with just a single ballot mark, which nearly two-thirds of Texas voters had previously done.

But the biggest reason has been the Democratic Party’s lurch toward the left in areas ranging from immigration and policing to sexual politics and the economy. That shift has opened up many Hispanics, who are generally culturally and economically conservative, to voting Republican.

The trend seems to be continuing under Biden. A late August Wall Street Journal poll gave Democrats an 11-point advantage over Republicans among Hispanics after they had enjoyed a 34-point advantage in the run-up to the 2018 midterm elections. In the South, Republicans and Democrats are essentially tied among Latino voters, according to a September New York Times-Siena poll.

Biden’s favorability among Hispanics has consistently declined, plummeting from 40% in October 2021 to 19% in July 2022. And an early October NBC News-Telemundo poll found that Democrats’ advantage with Latino voters has been cut in half since 2012. Fifty-four percent of Latinos now said they prefer Democrats to be in charge of Congress, while 33% said they prefer Republicans, a 21-point gap. The gap was 42 points in 2012.

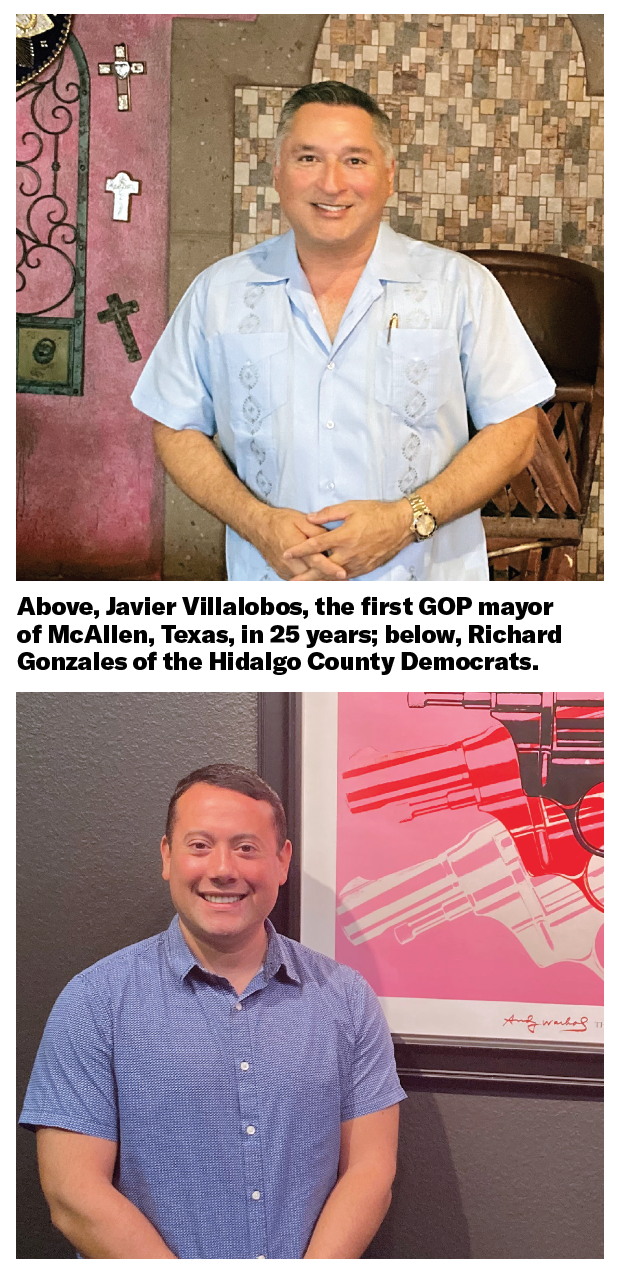

Richard Gonzales thinks about these trends a lot. Gonzalez leads the Hidalgo County Democrats. At his law office in Pharr, just east of McAllen, I asked him if he’s concerned about recent GOP success with Latino voters.

“I am concerned,” he said. “I mean, if I told you I wasn’t, that would be very ignorant of me — to tell you that that is not a problem. That is a problem. I’ve seen the data. I’ve seen where the trends are.”

Gonzalez discussed the Texas governor’s race, which pits popular conservative Republican incumbent Greg Abbott against former Rep. Beto O’Rourke, a progressive. Abbott won 44% and 42% of Texas Latino voters in his first two elections for governor and has pledged to win a majority this time.

Gonzalez seemed anxious about O’Rourke’s chances and what might happen if he loses.

“If Beto doesn’t win now, we’re not going to get a Democratic governor anytime soon,” he said. “Because I think he’s truly, like, the last great hope of Texas Democrats. If he loses, I don’t know what Democrat will come in and finally unseat the Republicans.”

Gonzalez encouraged me to attend an O’Rourke rally the following evening, assuring me it would be a lively affair.

And he was right. When I arrived at Railyard 83 Icehouse in Alamo, it was so packed that I couldn’t find a parking spot and had to park on a street a few blocks away.

I walked in and found hundreds of people filling the hall on a Thursday evening. Grammy-winning norteno band Solido, clad in Beto T-shirts, warmed up the crowd.

The mood was exuberant, and not without reason. At the time, Biden’s approval ratings had rebounded slightly from historic lows. The Inflation Reduction Act had recently been signed into law, and the FBI had just raided Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home. O’Rourke was polling within 6 points of Abbott. There was hope in the heavy late-summer air.

Various local and state candidates spoke. Chants of “Si, se puede!” and “Beto!” broke out at various intervals. Then Gonzalez took the mic and announced that O’Rourke would not be appearing. He was quarantining at home after contracting a bacterial infection.

The place suddenly quieted. Then, after a few seconds, the crowd began to chant:

“Beto!”

“Beto!”

“Beto!”

“Beto!”

But it lasted only a moment. Thirty minutes or so after I had arrived, the crowd was already dispersing. It seemed like a metaphor for the perennial hopes of Texas Democrats: Much anticipation, lots of noise, and then, suddenly, it was over.

The Rio Grande Valley has historically been dominated by Democrats. It’s also notorious for, and still infected by, political corruption — the kind of party-boss, crooked-judge type of corruption that one-party dominance often breeds.

The local economy relies on the many Mexican shoppers who travel up daily from Reynosa, a large and crime-ridden manufacturing center that sits directly across the border in Mexico.

But while McAllen is a hub of illegal border crossings, it’s quite safe.

“We’ve had over 425,000 immigrants pass through McAllen since 2014, and I don’t know of a single incident with one of them,” Javier Villalobos told me when we met at the Hacienda San Miguel Mexican Grill & Bar in McAllen. He said the only illegal immigrants he sees are in the bus station.

Villalobos was elected mayor of McAllen last year, the first Republican in a quarter of a century to hold the post. Though technically a nonpartisan race, everyone knew which party he represented.

“I was a Republican when being a Republican wasn’t cool,” Villalobos said, referring to his tenure a decade ago as head of the Hidalgo County Republican Party.

Back then, many residents, especially those on the poorer south side of town, wouldn’t even speak to Villalobos. But people seemed more open to him when he ran last year. That was the Trump effect, he said, and a consequence of how tired people had grown with local Democratic futility.

“Do you think Republicans are making real progress here?” I asked.

“I don’t think so, I know so,” he said. “It’s amazing what’s going on. When I was chairman, I told people, ‘We have been neglected, taken for granted.’ Competition has brought a higher caliber of candidate.”

He thinks Democrats are too extreme for South Texas and for the country. That includes O’Rourke, who he said is “just too liberal” for the area. He raved about the three Republican Latinas running for Congress, saying that if they can win, it’ll prove that Republicans’ success with Hispanics is no mirage.

But he was more nuanced about Trump, crediting him for the Republican ascendance here and a strong economy nationally while adding, “Unfortunately, we also got a little more divisiveness.”

He talked about Trump as if he was a house guest who’s overstayed his welcome.

“Is Trump still popular here?” I asked.

“He’s still relevant,” the mayor deflected.

“Would you support Trump if he runs again?”

“Eh,” he said, “Anyone can run for office.”

Daniel Allott is an opinion editor at the Hill and the author of On the Road In Trump’s America: A Journey Into the Heart of a Divided Nation.