“We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security,” President Donald Trump said on Jan. 5, “and Denmark is not going to be able to do it.” This was the icebreaker for a negotiation over Greenland’s reserves of “critical minerals,” especially rare earth elements. The outcome may lead to a gold rush as American companies extract next-generation resources from a new frontier in the freezing north. It may confirm the polarity of American-Chinese rivalry, with 21st-century mineral politics augmenting 20th-century energy politics. It may also backfire by breaking America’s Atlantic alliances with NATO and driving Europe’s faltering economies closer to Russia and China.

Trump’s loose talk about buying Greenland from Denmark or even conquering it grabbed the headlines and panicked European politicians. The Danes and their European allies sent a token force of human tripwires to Greenland. Trump retaliated with tariffs on eight European states, including Britain, France, and Germany, starting at 10% on Feb. 1 and rising to 25% on June 1. Privately, European officials called Trump “crazy” and “mad” and called his unprovoked “attack” a “step too far.” French President Emmanuel Macron called the tariff threat “unacceptable.” British Prime Minister Keir Starmer called it “completely wrong.” Trump was unmoved. “We have to have it,” he told reporters on Jan. 20. “They have to have this done. They can’t protect us.”

While in Davos, Switzerland, Trump seemingly ruled out taking Greenland by force. He also backed off his threatened tariffs, announcing the “framework of a deal.” But that is unlikely to be the end of the matter.

This land is your land

As usual with Trump, there is method to the madness, but the cost of the madness may exceed the profits of the method. As often, his allies failed to take him seriously and now find themselves to be his adversaries. He did warn them. In August 2019, the Wall Street Journal reported that the “former real-estate developer” had raised purchasing Greenland “with varying degrees of seriousness.” The new Danish prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, called the idea “absurd.” Her predecessor, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, joked it off as an out-of-season “April Fool’s Day joke.” But Greenland’s foreign ministry understood the gambit: “We’re open for business, not for sale.”

Trump was not just thinking that a bigly America is better. He knew that Greenland has critical minerals and that Russia and China are circling them. Denmark cannot defend the Arctic approaches to North America alone. In 2018, pressure from then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and the Pentagon had headed off a Chinese plan to build three airports in Greenland. As often, Trump raised panic by restating a piece of conventional wisdom that everyone in Washington has forgotten. Greenland was a national security interest before Trump was born. On April 9, 1941, the first anniversary of Nazi Germany’s occupation of Denmark, Henrik Kauffmann, Denmark’s ambassador to the United States, disregarded orders from the collaborationist government in Copenhagen and signed an agreement with U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull that made Greenland an American protectorate.

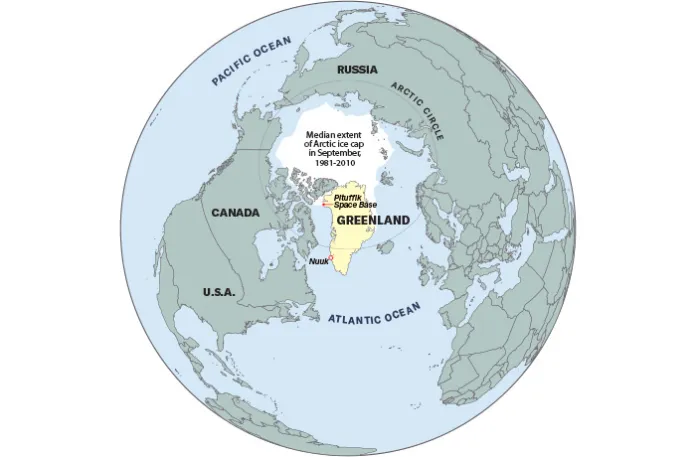

President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration invoked the Monroe Doctrine. American bases prevented Germany from seizing Greenland. The island became a critical naval base in the Battle of the Atlantic and a waystation for transferring aircraft to Europe — and then a critical Cold War front. In 1951, President Harry Truman’s administration secured the Greenland Defense Agreement with Denmark that led to the building of an air base at Thule, now Pituffik Space Base, 750 miles north of the Arctic Circle. In the Cold War, Greenland was essential to ballistic missile early warning systems and monitoring the “GIUK gap,” the maritime passage between the Arctic and the Atlantic Ocean that was overlooked by Greenland, Iceland, and the U.K.

Politically, Greenland is part of the European Union. It is a semi-autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, much as Puerto Rico and Guam are semi-autonomous territories under American sovereignty. But Greenland is part of geographical North America. The Inuit, who form the majority of its 57,000 people, are indigenous North Americans. And though Greenland is NATO territory, it is perhaps the most extreme example of NATO’s function as a multilateral legitimator of American power. In law, Greenland’s foreign and defense policies are controlled from Copenhagen. By treaty, and by military presence and capacity, the U.S. has an effective veto on both.

Greenland has extensive reserves of 25 of the 34 raw materials that the European Union considers “strategically important for Europe’s industry and the green transition.” They include gold, zinc, iron, oil, gas, critical minerals, and 1.5 million tons of rare earth deposits, the world’s eighth-largest. In November 2023, the European Union and Greenland signed a “strategic partnership” memorandum on developing “sustainable raw materials value chains” from Greenland’s reserves. As the scramble for critical minerals intensified, the Europeans, like the Americans and Chinese, tried to find the metallic elixir of security and value on their own turf. The global race for mineral and rare earth autonomy makes that turf and what is hidden beneath it an American interest that cannot be ignored.

Trump put it bluntly on Jan. 19 as he prepared to confront European leaders at Davos. “Look, we have to have it.”

Cold metal

There are 17 rare earth elements. They have sci-fi names such as lanthanum, neodymium, and promethium, but wars will be fought over them. Along with rare minerals such as lithium, tungsten, and molybdenum, rare earth elements are vital to next-generation civil and military technologies such as electric car batteries, artificial intelligence, wind turbines, weapons, computers and smartphones, medical imaging machinery, aerospace technology, and semiconductors.

By the early 2000s, Chinese mines produced 95% or more of rare earth elements, and Chinese businesses monopolized their processing. In 2010, China imposed restrictions on rare earth exports, interrupting supply chains on items such as Toyota cars and iPods, and causing prices to surge by up to 4,500%. The World Trade Organization ruled in favor of an America-led complaint in 2015, forcing China to drop its restrictions. But the strategic implications of China’s stranglehold on rare earth mining and refinement were obvious. America’s policy response has been slow. Today, China still accounts for 61% of rare earth extraction and 92% of the refining.

In 2017, the first Trump administration created a list of “critical minerals” such as copper, lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare earth metals that were “essential to the economic and national security of the United States” but had supply chains “vulnerable to disruption.” The Biden administration continued the work of building domestic “mine-to-magnet” production, notably with the CHIPS Act of 2022, which stimulated semiconductor research and manufacturing, but also by encouraging American investment in Greenland’s mines. In September 2024, the Biden administration successfully pressed Tanbreez Mining, the developer of Greenland’s largest rare earth deposits, not to sell its mines to Chinese developers, but to accept a reportedly lower bid from Critical Metals, a U.S. subsidiary of the Australian firm European Lithium.

In February 2024, Greenland’s government announced plans to move toward independence. By the end of the year, as Trump planned his second administration, he was calling American “ownership and control” of Greenland an “absolute necessity.” In March 2025, Trump issued an executive order intended to jumpstart domestic mineral production “to the maximum possible extent.” After the administration’s April 2025 import tariffs and ban on American semiconductor exports, China retaliated by banning exports of seven rare earth metals and related technologies. The October 2025 summit between Trump and Xi in Busan, South Korea, lowered the tension a little. Xi agreed to suspend the expansion of export controls for a year, and Trump agreed to lower tariffs on Chinese imports from 57% to 47%. But the battle lines are drawn.

The Trump administration has directed federal investment to new mines, made it easier for corporations to obtain federal subsidies, and bought direct stakes in commercial mining companies such as Trilogy Metals, which is backing copper and cobalt mines in Alaska. While China mines lithium in Mali and rare earth metals in Tanzania, the Trump administration has struck a deal with the Democratic Republic of Congo, which has 70% of the world’s proven cobalt reserves. Now, it is looking closer to home.

Forgotten front line

Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, is roughly equidistant between Copenhagen, 2,200 miles southeast, and Washington, 2,000 miles southwest. Boston is equidistant between Nuuk and Dallas, 1,700 miles in each direction. A B-2 bomber can leave Pituffik Space Base on Greenland’s west coast and cover the 1,850 miles to Russia’s year-round deepwater port and nuclear air and submarine bases at Murmansk, near the Russian-Norwegian border, in about three hours. But the Nares Strait between Ellesmere Island, in the northern Canadian territory of Nunavut, and the northwestern tip of Greenland is only 16 miles wide. This is 5 miles tighter than the narrowest point of the English Channel between Britain and France, and 35 miles tighter than the 53-mile narrows of the Bering Strait between Russia and Alaska.

For most of the year, only icebreakers can navigate the Nares Strait. But in summer, tourists cross from Canada and visit tiny Hans Island, which is disputed by Canada and Greenland, and the abandoned Inuit village of Etah on the northwestern tip of Greenland. The Black Feather wilderness adventure company offers summer kayaking tours from Alexandra Fiord on Ellesmere Island. There are arctic foxes, polar bears, and muskoxen, as well as ruins and artifacts from the “paleo-Eskimo” Dorset culture; the Thule people, who were the ancestors of the modern Inuit and Yupik peoples; and the Vikings, who arrived with Erik the Red around A.D. 985 and were the ancestors of the Danes and Norwegians who claimed Greenland in 1397. In 1814, Greenland became a Danish colony. It became part of Denmark itself in 1953, was granted partial autonomy in 1997, and became a self-governing nation in 2009.

Across the strait is Etah, the departure point for Robert Peary’s failed polar expeditions. Some of his descendants still live about 70 miles away at Qaanaaq, Greenland’s northernmost town, along with the Inuit who were displaced in 1953 to make way for the Thule air base. The northernmost Defense Department installation, it was built secretly and discovered in June 1951 by a French geographer and his Inuit companion who were on their way back from the North Pole. Now Pituffik Space Base, it has a 10,000-foot runway, the world’s most northerly deepwater port, many of the Space Delta 4’s network of missile warning sensors, and the space surveillance sensors of Space Delta 2. The Danish flag still flies next to the Stars and Stripes at Pituffik, but the U.S. obtained unrestricted access in 2004.

The terrain is shifting beneath the feet of the 150 or so Americans serving on the Pituffik base. Long-term climate changes are extending the “melting season” and the summer. The Arctic Ocean is getting warmer.

The polar ice cap has been contracting and thinning at a rate of somewhere between 2% to 3% per decade since at least the mid-20th century. The Atlantic and Pacific oceans are now connected in summer by the Northwest Passage through the Canadian Archipelago and the Northeast Passage along Norway and Russia’s northern coasts, and navigable by ships strengthened against contact with floating ice. These passages may join the Strait of Hormuz, the Suez Canal, and the Malacca Strait as the pinch points of global trade and naval transit.

The ice is also retreating from the land. In 2025, Nature Climate Change reported that retreating glaciers created over 1,500 miles of “new” coastline and 35 “new” islands in the Arctic between 2000 and 2020. Two-thirds of the new “paraglacial” coastlines were in Greenland. On Google Maps, the strip of coast below Etah is green, and the white that shows the permanent glacier has retreated up to 20 miles from the shore. The new physical geography of Greenland and the drive to secure its resources symbolize an intensifying global struggle over resource competition. That challenge is rebalancing the map of resources and alliances. It will drive the historical development of the U.S. in a direction that, in its 250th year, seems both to echo its past and hint at its future.

The ‘Donroe Doctrine’

Trump’s musings suggest a return to the age when the U.S. was a hemispheric power that grew by purchase. The U.S. became a continental power through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The Gadsden Purchase of 1853 secured the southern parts of Arizona and New Mexico. Russia sold Alaska in 1867. Denmark contributed to these precedents by selling the U.S. Virgin Islands for $25 million in 1917. Trump has talked about augmenting the U.S. with Canada, Mexico, and the Panama Canal. If he has yet to mention Cuba, it is because there is no need. Cuba has never looked more likely to fall back into the American orbit. The administration has cut off the supplies of Venezuelan oil that keep the lights on in Havana.

“I strongly suggest they make a deal, BEFORE IT IS TOO LATE,” Trump posted on Jan. 11. The locking of caps on the presidential keyboard is a sign that more serious gear may be locked and loaded. No president since Teddy Roosevelt has ridden over law and custom like Trump has, and Roosevelt did his Rough Riding before he became president. That, though, was in the days of American expansion and European empire. These days, the Europeans, as Trump observes of Greenland, cannot defend their own turf, let alone rule someone else’s. And Trump is committed to expanding and contracting America at the same time.

The National Security Strategy issued in December 2025 seeks a hemisphere “free from hostile foreign incursions or ownership of key assets,” to control “critical supply chains,” and secure “continued access to key strategic locations.” But it is more focused on illegal immigration and “narco-terrorists, cartels and other transnational criminals” in its backyard than on confronting China on the other side of the Pacific. The aggressive tone of the “Donroe Doctrine” masks “hemispheric” retrenchment before the pressures of a multipolar system.

As international institutions fail and allies flounder, force remains the last reliable instrument of foreign policy. In June 2025, the U.S. sent B-2 bombers to central Asia and hit Iran’s nuclear program in a combination of reach and accuracy that no other power can match. In a night raid on Jan. 3, U.S. special forces abducted Venezuela’s narco-communist dictator, Nicolas Maduro, for trial in the U.S., a precision operation whose skill and elan only Israel could equal. China buys about 80% of Iran’s oil exports and bought an estimated half of Venezuela’s oil exports before Maduro’s capture.

In Ukraine, the familiar 20th-century politics of carbon fuel and petrodollars intersect with the new struggle over minerals and metals. Ukraine holds about 5% of global rare earth reserves and has around 500,000 tons of lithium. The administration proposes to secure a postwar Ukrainian state not by the traditional and expensive method of infantry garrisons and air bases, but by inserting state-sponsored, revenue-generating American corporations to manage the extraction of key resources. Perhaps Trump’s tough talk is a bluff that seeks a similar outcome in Greenland.

For the Europeans, this is the worst of both worlds. America is abandoning them. It is damaging what remains of their strategic credibility as it goes and now threatens to bully them out of the profits of their mineral reserves. That Trump is doing this to preempt their common enemies on the Arctic front is little consolation to the Europeans, who are too weak to secure their position themselves. This is not entirely the fault of the Europeans. For decades, Western Europeans revalued their willed weakness as moral strength. For decades, their American patrons encouraged their dependency.

America needed Western Europe in the Cold War as a market, hence the Marshall Plan, and a platform to prevent the Soviets from advancing westward, ideologically and militarily. America required Britain, France, and West Germany to settle their historical grudges, dilute their differing needs, maintain strong militaries under American leadership, and enjoy political stability and the material fruits of reconstruction. An independent Western European military was never an American goal because it was not in the American interest. Even now, with isolationist impulses stronger in the Republican Party than at any time since 1941, only a minority prefers an independent European military to a U.S.-controlled one.

The Europeans always felt differently. The European Union was supposed to become the vehicle that returned Europe to historical eminence, with the Euro currency as its fuel. That did not work out. Every president since Barack Obama has called on the “free riders” of Europe to organize their own defense. Only now are the Europeans heeding the warnings, but it is too late. They have neither the money nor the electoral support for rearmament. They feel insulted by Trump, but no European state has said it is leaving NATO — not even France, which left and returned before. They have never needed America more since the Cold War. They have never liked it less.

As usual in these exceptional times, Trump’s style works against his content. His opening gambit on Greenland has derailed relations with Europe and is the worst self-inflicted injury to the security architecture of the Western Alliance since the Suez Crisis of 1956. He has discredited the rising nationalists of the European Right who would otherwise remain the natural allies of Trump’s America. His abusive and arrogant behavior encourages European voters and leaders to stick with the failed social democracy of the 1990s and the budgetary policies that have enfeebled their nations.

It might suit Europe’s leaders to claim that, as the American president no longer cares for the alliance system that American presidents created, they, too, should feel free to renege on their NATO commitments. That would get them off the hook of the welfare cuts, without which they cannot revive their militaries. But it would also amount to strategic surrender and a drift into intimidation by Russia and economic dependency on China.

None of this would be in the American interest. Nor would it be in the American interest to collapse NATO, whose Atlantic security system is also an Arctic one. What does it profit a president if he gains the critical minerals of Greenland but loses America’s global footing?

Dominic Green is a Washington Examiner columnist and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society. Find him on X @drdominicgreen.