As one of Don DeLillo’s displaced East Coast professors says in the novel White Noise, “California deserves whatever it gets. Californians invented the concept of life-style. This alone warrants their doom.” California has always been a screen for America to project its feelings onto. Even its staggering natural violence, from mudslides to fires, earthquakes, and droughts, counterpoints to its reputation for perfect climate, are themselves incorporated into the larger narrative of acquisitive dreaming and libertine utopianism.

These are the basic components to the fantasy of California: the implacable otherness of nature mingling with the dreaming human mind at the edge of the continent. Within this melange, nature always seems to have the upper hand. Far from reducing art to frivolity, this relationship liberates it in some sense, like a small fish riding the wake of much larger and completely oblivious sharks. And so, while there may not be one single “California style” in literature and poetry, surely there’s a unifying spirit that relishes proximity to the serrated edge of things.

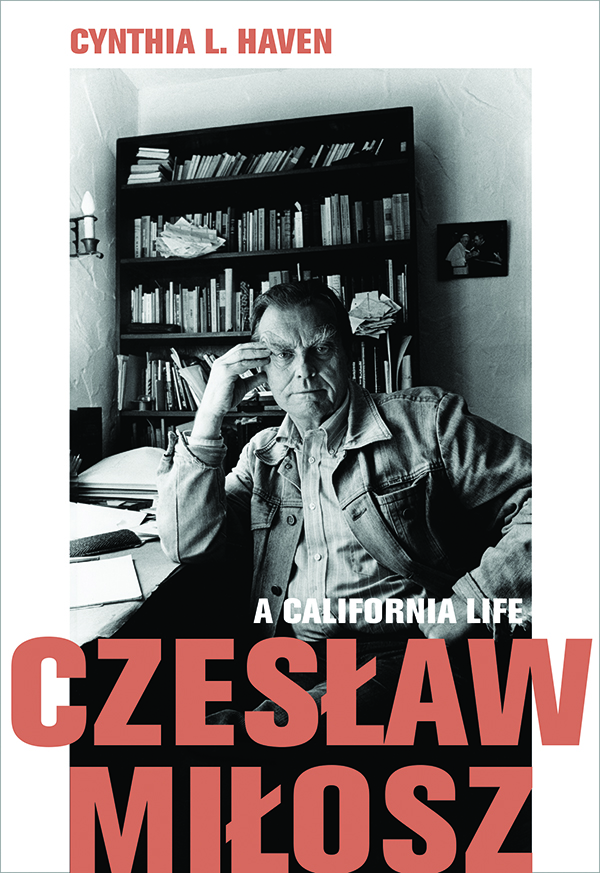

Cynthia Haven, celebrated author of 2018’s Evolution of Desire: A Life of Rene Girard as well as two previous books about Czesław Miłosz, brings this energy to bear in her latest work, A California Life: Czesław Miłosz. More daring and more rewarding than a straightforward biography of the self-exiled Polish poet, A California Life channels the tensions between Miłosz and his adoptive home and lets that friction energize the project. In other words, this is less about a poet and his life and more about how a brilliant artist and thinker steeped in Old World culture learned to exist in the amnesiac fog of California. As Haven eloquently describes it near the beginning of the book:

“At first, [Miłosz’s] preoccupations, almost obsessions — history, language, civilization, time, and truth — seemed irrelevant in the place in which he had, half reluctantly, made his home. Yet over time, these two worlds, these two realities — California and Eastern Europe — reflected, illuminated, even interpenetrated each other. In doing so, they transfigured him from a poet writing from one corner of the world to a poet who could speak for all of it; from a poet focused on history to a poet concerned with modernity and who, always, had his eyes fixed on forever.”

As Haven suggests above, Miłosz came to California out of necessity, so he was far removed from the gold-rush mentality that has typified so many immigrants to California in the past. And it was a terrible necessity. Not all poets lead interesting lives, but some are cursed to. Born into the Kovno Governorate of the Russian Empire, a country that ceased to exist after the First World War, he lived through and escaped the siege and Nazi occupation of Warsaw, eventually becoming one of the first notable defectors from behind the Iron Curtain. A brief gloss of his young adulthood, however, can’t begin to suggest the intense pain and upheaval of Miłosz’s time and place. Nor can it fully suggest the effect these tribulations had on a poet with Miłoszs cultural background. But as Haven reminds us, “Whether these trends, or history itself, seeded the literature that followed is an open question.” The relationship between Miłosz’s loss, both physical displacement as well as cultural, can’t be reduced to a simple input/output formula. And Miłosz wouldn’t be much of a poet if it could. As Haven writes, Miłosz “decried the era’s nationalism and idealism,” always resisting attempts, as he put it, to “force every poet into the role of National Bard.” Instead, he opted for the vatic tradition running like a seam of rich ore through Polish and Lithuanian poetry. “When Miłosz wrote ‘I am no more than a secretary of the invisible thing,’” Haven explains, “he was, perhaps, voicing a variation of the bardic notions that had been articulated by so many others.” Searching, as his poetic hero Eliot did, for the vision to see where eternity intersects the mundane allowed Miłosz to not so much transcend his historical context as synthesize it into a deeper wisdom.

Understanding this, though, is only the beginning of appreciating what a triumph A California Life really is. Haven gives us Miłosz in all of his specific granularity: the way he dotes on the deer visiting his home on Grizzly Peak in Berkeley, his relationships with students and other poets, his relationships with his children. But as the philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset said, we are ourselves plus our circumstances. And in this book, Haven gives the circumstances a life equal to the human subject. There are too many beautiful passages to mention, but one that particularly stands out is when California wildfires are placed beside the destruction of Warsaw:

“We are choking on the air, which is filled with particles of everything that has burned so far. We inhale not only the blazing houses and stores and garages but also what’s in them, all this is toxic when airborne — asbestos in roofs and siding, car batteries, cadmium in television sets and mercury from old thermometers, detergents and cleaners, the contest of medicine cabinets, nail polish remover, paint thinner, light bulbs and electronics — all go up in the smoke plumes and fumes. We inhale the dead, too, with every breath we draw.”

This parallels, or perhaps rhymes, with the annihilation of Warsaw by the German engineers who were used to ensure total destruction. But it also in some sense captures the effect that Miłosz’s experiences had on his poetry. He didn’t simply write about the vanished buildings and people. He inhaled the dead and exhaled poetry.

A California Life is ultimately a book about relationships. Miłosz with California. Haven with Miłosz. Haven with California. California with the world. However, the sum is greater than the parts of this rich, knotted matrix. Some biographies succeeded by the biographed becoming translucent, by allowing us almost voyeuristic access to the subject. But in A California Life, Haven the biographer herself is intensely present, and necessarily so. When she includes her own experiences with Miłosz or moving to and living in California, it feels less like an intrusive aside and more like a quorum has finally been achieved. This book is less a biography than an occasion for the deepest engagement with art and life. We need more books like this.

Scott Beauchamp is an editor for Landmarks, the journal of the Simone Weil Center for Political Philosophy. His most recent book is Did You Kill Anyone?