“Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work,” Gustave Flaubert is purported to have said, and who could argue?

From Louis Auchincloss to John Updike, some of the most memorable writers of the last century are those who maintained largely uneventful, even dull daily lives as they crafted works of fiction of spirit and daring. By contrast, writers who sought to live as recklessly as they wrote — say, Norman Mailer — aren’t looking as good by today’s censorious standards.

Occupying a curious middle ground is the case of Elizabeth Hardwick, a critic of keen perceptions, a short story writer and novelist of considerable gifts, and, by all accounts, an even-tempered, well-adjusted woman. Yet in the eyes of the reading public, Hardwick will always be yoked to her first and only husband, poet Robert Lowell, whose psychological problems (and resulting hospitalizations), extramarital affairs, and public airing of grievances with his wife mark him as among the most volcanic literary figures of his age.

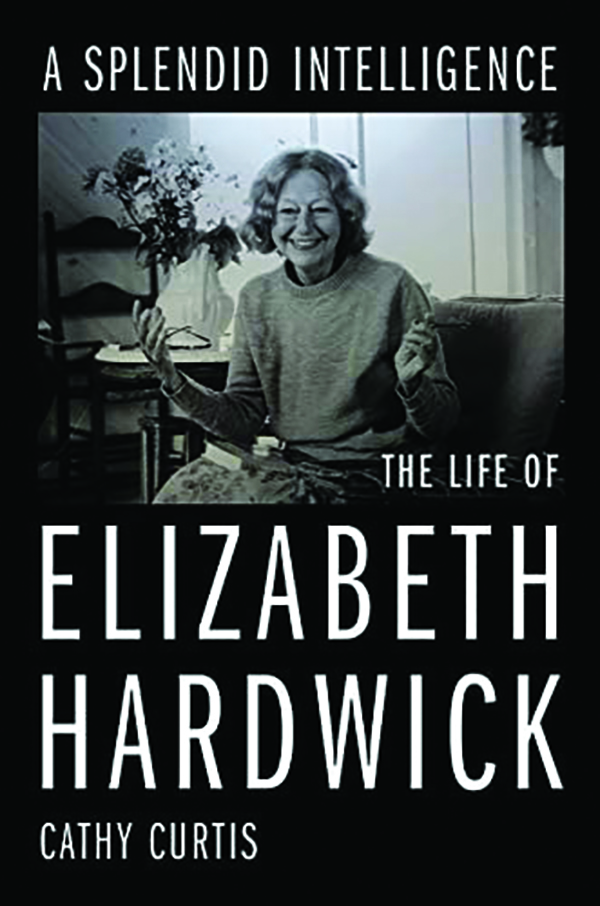

In the scrupulously researched new biography A Splendid Intelligence: The Life of Elizabeth Hardwick, Cathy Curtis again and again presents Hardwick as an elegant, mannerly woman with her head on her shoulders who lashed out mainly in print. The fourth-youngest of 11 children born to Eugene and Mary Hardwick in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1916, Elizabeth was a bookish girl, “discovering Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice because it was shelved under Mysteries” at the public library, Curtis writes. Describing Hardwick’s yearbook photo at the University of Kentucky, Curtis notes the “serene expression” on her face, redolent of “a woman who had come to know what set her apart from others and what she wanted from life.” Elsewhere, Curtis writes of Hardwick’s stylishness and lifelong tendency to grow fatigued as a kind of essential feature of her character, writing, “She would often write to friends about taking pleasure in being able to get to sleep early.” Remarked friend Ginnie Foote: “Even going to the dump, she’d put her lipstick on.”

What, then, was a woman as poised as Hardwick doing with a man as fiery as Lowell? As a Kentucky native making the rounds among the New York intelligentsia during the war years and after, counting the poet Allen Tate among her early lovers, and with stories published in places such as the Yale Review and the Sewanee Review, it was probably inevitable that Hardwick would at least run into Lowell (called “Cal”).

In fact, their first meeting only took place because Hardwick had become a member of the Partisan Review gang: The future couple first set eyes on each other at a party in the summer of 1947 given by the publication’s co-editor, Philip Rahv. In a poem written years later, Lowell commemorated the occasion: “Too boiled and shy / and poker-faced to make a pass / while the shrill verve / of your invective scorched the traditional South.” Hardwick’s next encounters with Lowell were at the Yaddo artists’ colony in New York and a poetry reading at Bard College that was also attended by Elizabeth Bishop, James Merrill, and William Carlos Williams — almost too-perfect settings for a midcentury literary romance.

It must have seemed like an intoxicating whirl of excitement to someone from the sticks, even one as intellectually formidable as Hardwick, but storm clouds loomed. When he met Hardwick, Lowell, a blue-blooded Bostonian famous for his conversion to, and subsequent de-conversion from, the Catholic Church, had recently divorced Jean Stafford, but he anguished over whether to return to the church and, therefore, whether to formalize his relationship with Hardwick. “As a Catholic, he believed he could neither remarry nor commit adultery,” Curtis writes, but Lowell’s hemming and hawing wasn’t really a matter of dogma but a manifestation of mental illness. “Unbeknownst to Elizabeth, he was in the grip of escalating mania, a recurrent sign of the bipolarity that plagued his adult life.”

Lowell and Hardwick married on July 28, 1949. In Curtis’s authoritative telling, the date has an ominous, fateful quality. Marriage, even one between two writers, ought to represent the beginning of solidness and security, but Lowell and Hardwick’s life together was anything but. Following a period of itineracy that saw them hopscotch throughout Europe, the couple made it back to the United States in 1953. Yet, on any continent, Lowell comes across as self-indulgent, unpredictable, sometimes heartless, and often ungovernable.

Stoically, Hardwick tended to her husband’s needs while furthering her own literary ambitions — even as she shouldered the burden of a marriage to an unwell man, she churned out now-classic pieces of criticism, such as “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” and she contributed to the founding of the New York Review of Books. Hardwick wrote, “The most depressing fact is that Cal and I have, by some strange miracle, a good marriage and great love for each other, except in these manic months and just before they come on.”

That’s an awfully big qualification, and probably too big a miracle to believe in, but credit must be paid to Hardwick for her wifely devotion and literary perseverance. For this, Lowell repaid his wife with a two-pronged betrayal. In 1970, Lowell initiated a romance with Lady Caroline Blackwood, and in 1973, he quoted and/or concocted Hardwick’s letters to him in a book of poetry, The Dolphin (a Pulitzer Prize-winner). By then, divorce was inevitable. In 1972, Lowell and Blackwood, then the parents of a boy, married, though Hardwick forever declined to characterize her former marriage, even in hindsight, as something to regret.

Alas, this biography loses steam when Lowell leaves the picture — one has the sense that every stray assignment Hardwick received until her death in 2007 is detailed, and it’s not exactly compelling reading. Yet it’s undeniable that Hardwick’s best work, chiefly her criticism and her late novel, Sleepless Nights, is far more widely read today than Lowell’s. At one point, Curtis, who for the most part tells this story dispassionately, implies that Hardwick was held back by motherhood — she had one daughter with Lowell, Harriet, and “it was unimaginable to want a second child” — but, of course, Shirley Jackson and her brood of four, to say nothing of Phyllis Schlafly and her brood of six, belie the feminist cliche that a woman of letters must, by definition, be childless or close to it.

In fact, if Hardwick was constrained by anything, it wasn’t motherhood but her strange loyalty to that mad cad called Cal.

Peter Tonguette writes for many publications, including the Wall Street Journal, National Review, and the American Conservative.