Immigrant fiction, in which minorities suffer the debilitating indignities of American life, has long been a favorite genre of the literary establishment. White editors salivate over stories of brown victimization, which is why most books about immigrants are somber and suffused with a seriousness that makes for an unpleasant reading experience. Writers know that they’re expected to produce weepy, moralistic tales of minority suffering, and the books that result are less literature than they are sociopolitical treatises on the struggles of people of color.

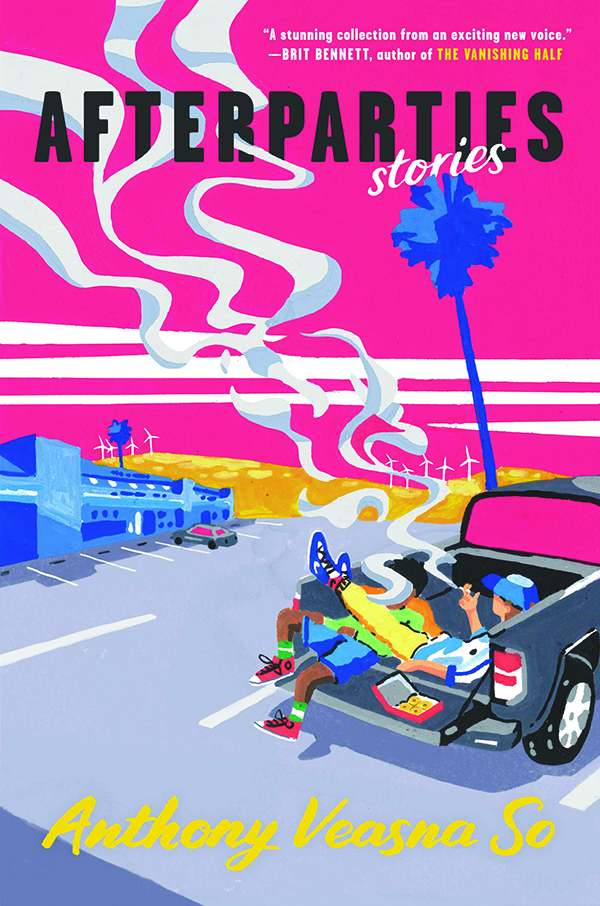

This season’s immigrant fiction jewel, Anthony Veasna So’s Afterparties, thankfully deviates from these tired tropes. A short story collection about Cambodian Americans whose families escaped the Khmer Rouge genocide, Afterparties is an exuberant, often hilarious book in which young “Cambos” deal with the specter of generational trauma while trying to navigate modern American life. So, who died of a drug overdose in December at the age of 28, was obviously aware of the limitations of the genre in which he was working. Afterparties isn’t another sob story but a comedy tinged with tragedy — a stylistic wrinkle that makes all the difference in the world.

Stories such as “Superking Son Scores Again,” about a middle-aged former badminton prodigy who runs a Cambodian grocery store and moonlights as the badminton coach of his high school alma mater, highlight the hilarity and quiet desperation of immigrant life without leaning into sentimentality. Superking Son is “an artist lost in the politics of normal, assimilated life” who reeks of “raw chicken, raw chicken feet, raw cow, raw cow tongue, raw fish, raw squid, raw crab, raw pig, raw pig intestine, and raw — like really raw — pig blood.” He’s burned out from operating the grocery store and is neglecting his coaching duties as a result. When Justin, a badminton star and the son of rich Cambos, transfers to Superking Son’s school and joins the squad, Superking, disgusted at the sight of an earlier version of himself who hasn’t yet squandered his potential, starts a feud with his new top player.

Superking Son does everything possible to get Justin to quit, including naming him rank 3 on the team when he’s clearly rank 1. Justin, frustrated but unwilling to give up, challenges Superking Son to a badminton match, promising to leave the team if he loses. Superking Son wins, and as with every has-been who’s forgotten the taste of victory, he gloats and challenges the rest of his team. Watching their coach, the players realize that on a long enough timeline, even their heroes will become losers: “What we remember was this: the shock of witnessing Superking Son’s inflated ego spurting all over the gym. Our bodies settling into pity. We looked at our beloved coach, an overgrown son prone to anxious, envious tantrums, who was fed up with his place and inheritance, who was perpetually made irritated, disgusted, paranoid by his own being, and then we looked at each other.”

Unlike other immigrant books in which the perpetual melancholy lulls the reader into a numbing boredom, Afterparties is full of humor, which makes its moments of sadness all the more affecting. In several of the stories, the comedy is delivered by hip Cambo failsons who’ve entered the elite but don’t quite fit in, and who are disgusted by the superficial wokeness of their new cohort. The narrator of “Human Development,” for instance, is a Stanford University graduate who floats at the periphery of the San Francisco tech scene, disaffected by the fact that his “job was to teach rich kids with fake Adderall prescriptions how to be ‘socially conscious’ at a private high school in Marin.”

In the collection’s stronger stories, the characters are more connected to America than they are to the familial homeland. They are Cambodian, yes, but they are also young Americans like any other. The narrator of “Human Development” is queer, but his struggle isn’t with societal homophobia or his traditional family — it’s with navigating the sexual marketplace: “It took real intuition and finagling to sift through the preponderance of white-on-white-on-white-on-white profiles — the white muscle daddies and sparkling white twinks, the white otters and white gaymers, the white gym rats trying to sell steroids to doughy white tech bros.” This slangy language lends the best stories in Afterparties a stylistic swagger.

So, however, does not maintain this style throughout. His weaker stories are the ones in which it is obvious he was attempting to write an Important Immigrant Story, with all the dourness that entails. The book’s final story, “Generational Differences,” opens with a young boy finding a photo of Michael Jackson visiting an elementary school classroom. The boy questions his mother, a longtime teacher, about the photo’s meaning, and after long deliberation, she finally tells her son about the school shooting she survived before his birth. The singer, she tells her son, visited the school after the tragic event: “When his helicopter landed on the concrete playground, countless security guards issued from open doors, like solemn clowns from a tiny car, all of them intimidating in their sunglasses, their black suits imposing an air of restrained brutality. It made me furious to witness the commotion, all of this nonsense, on the very ground those children had died. Their blood was staining the pavement.”

“Generational Differences” is an attempt at high-brow literary fare with a gimmicky conceit and an appearance by a pop star. It fails to capture the energy and looseness of So’s comedic stories because it is so invested in signaling its own seriousness. Juxtaposed against his electrifying tragicomedies, stories like this one offer a crucial reminder: Successful fiction is driven by tone, aesthetics, and a writer’s natural stylistic inclinations.

Afterparties is a raunchy and raucous debut from a talented young writer who was certainly well on his way to a towering career. So, at his best, was a virtuosic master of the short form with an incredible ear for dialogue and comedic chops rarely seen in the literary world. This hipster Cambo will be missed.

Alex Perez is a fiction writer and cultural critic from Miami. Follow him on Twitter: @Perez_Writes.