We live in a golden age of stupidity, and it is a source of endless amusement for those capable of surmounting or ignoring the horror it initially inspires. By stupidity, I mean here not ignorance or mental ineptitude but the flamboyant productions of inadequate minds determined to apprehend matters far exceeding their capacity. We might call it “creative stupidity” to distinguish it from stupidity as a simple shortcoming. I think of my relative who learned the term “fiat money” and could not go a day without repeating it, convinced that the abandonment of the gold standard was an unpardonable fiduciary sin he was tasked with revealing to the world after discovering it on YouTube; of the helpful coronavirus hints that pullulate on WhatsApp, generally sent by people prone to deriding doctors and virologists as clueless; or of Frazzledrip, which I might never have heard of but for the rise of Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, who represents the district I grew up in.

It is strange that something so common has provoked so little serious investigation — almost as if it had never occurred to anyone to write about the sea or the sky. Particularly in the United States, with its stubborn faith in the power of bootstraps and treacly susceptibility to miscreants-turned-self-help entrepreneurs, things best explained by stupidity are often cast as failings of morals or character. H.L. Mencken loved to deride Homo boobiens, in his wonderful turn of phrase, but when you cut through the flourishes of his style, the ideas are scarce, and many of them are bad. Walter Pitkin, a forgotten professor of psychology, made a serious go at the topic with his Short Introduction to the History of Human Stupidity. It is not short, but it is strikingly racist, and his conclusion that “the year 2000 will probably see an end of those varieties of mass stupidity in the United States and the Western World” inclines one to think he should have been one of the book’s subjects rather than its author.

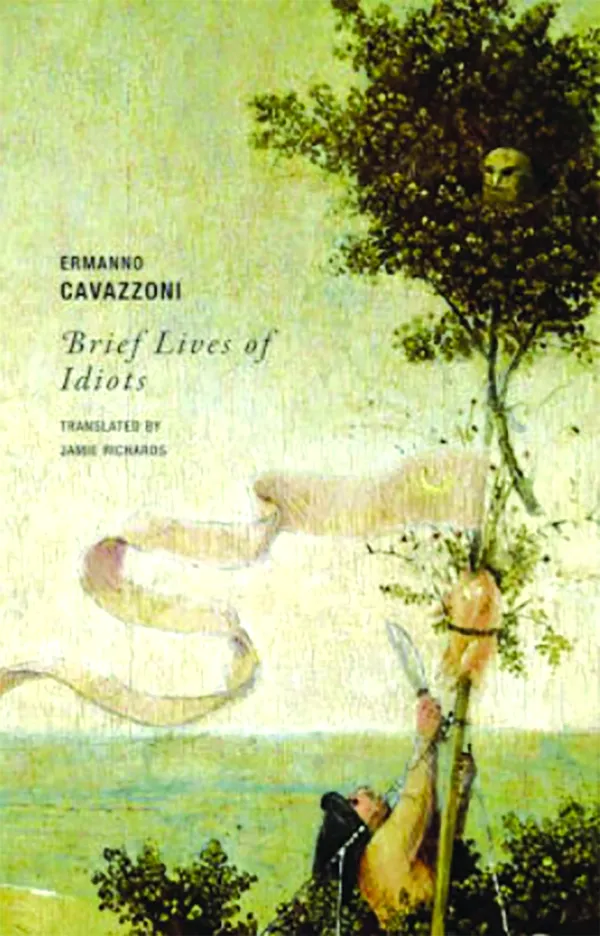

In Italy, on the other hand, the literature on stupidity is abundant. In 2016, mathematician Piergiorgio Odifreddi published a dictionary of stupidity, an amusing, if at times reactionary, denunciation of the profuse targets of his contempt, including memes, Scientology, Tolstoy, and the letter K. In his essay “The Philosophy of Stupidity,” Fausto Pellecchia describes stupidity as “the reduction of the world to ‘me,’ of the other to the same,” and he writes that the stupid person prefers recognition to discovery — pointing to a cardinal aspect of the actively stupid person: He almost always thinks he understands. Little Italian writing gets attention in English, but thanks to translator Jamie Richards and the Wakefield Press, readers can enjoy a fictional gem on stupidity in some of its more ornate forms: Ermanno Cavazzoni’s Brief Lives of Idiots.

Cavazzoni has a taste for the compendiary: Having translated and adapted hagiographer Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend, he has gone on to publish a volume devoted to fortunate deaths, a typology of useless writers, a history of giants, and a guide to legendary animals (many of which actually exist, but not precisely as Cavazzoni describes them). Brief Lives of Idiots contains 31 tales, one for each day of the month, recounting the eccentricities of “a kind of saint, who experiences agony and ecstasy the way traditional saints do” but in relation to the wrong sort of objects, or indulging these sublime emotions in ways that elicit laughter or contempt. Mr. Pigozzi, inspired by the tale of an East German who escaped the communists by flying a homemade plane over the Berlin Wall, decides to build an aircraft from a Fiat parked near a junkyard to escape his wife and daughter. Mr. Pellagatti struggles to reconcile his belief that Jesus was an alien, “probably fallen off a missile on Christmas night,” with his faith in Marxism, and he is rejected by both Marxists and Christians. One day, he encounters a retired pastor, Don Pelacani, who tells him Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels never existed but that they were two twins who rented beards and passed themselves off as the legendary communists to benefit their cause. A town of idiots is thrown into chaos after Fat Tuesday in 1956, when a resident refuses to remove one of the novelty noses passed out as a disguise by the town council.

For the (real) economic historian Carlo Cipolla, who considered stupidity a civilizational crisis, the stupid person was one whose efforts caused harm to himself and others. Idiots of this sort are exemplified in Cavazzoni’s book in a series of near and “collateral” suicides. The collateral suicides are failed attempts that result in the death of another: a butcher who tries to shoot himself but accidentally kills a contractor; a chicken seller who lies across the railroad tracks, giving a heart attack to a passenger when the rain shrieks to a halt. The near-suicides are, for the most part, inept attempts, but the last of them relates a senseless death in which fate, malice, and witlessness all have their parts:

After lunch, a forty-three-year-old man had the bad habit of keeping a wedge of apple in his mouth and rolling it around with his tongue. His mother would say, “swallow that, quit acting stupid.” He pretended to swallow it but secretly kept it in. One day in November, his mother, after telling him repeatedly to “swallow that apple,” smacked him on the back of the head. The apple went down his throat and got stuck. Nothing helped, no matter how much they hit his back, and he choked to death. Thus the news that he committed suicide because of his insubstantial, drab life is false.

There is compassion in Cavazzoni, and his idiots have something in them of Italo Calvino’s Mr. Palomar. But while Calvino’s human telescope sees deep into the essence of the ordinary, Cavazzoni’s characters aim, but stubbornly fail, to penetrate the extraordinary. There is a sly one, though: Melegari, protagonist of “The Poet Dino Campana,” who arouses deeper questions about the purpose of knowledge and whether it would matter if everything we knew were rubbish. Melegari, born in the same town as the poet from the title, never fails to mention this fact when he sits for his exams. This circumstance, and a few odd bits of trivia he picks up, suffice as the foundation for an academic career. Melegari purchases a thesis from a student who never graduates himself, being too busy writing theses for other people, and with time, he becomes a Dino Campana expert without ever bothering to read Campana’s poetry.

This reminded me a bit of a time when my mother and sister visited me in Philadelphia. I thought it a good idea, god knows why, to give them a historical tour of the city. Seeing their evident boredom, I asked myself whether there was any point to what I was telling them and whether I might not as well have substituted other information, fact-like but with a little more dash to it. I suppose I am beginning to find out. A decade later, thanks to the loss of prestige among legacy media, the rise of an industry of self-described news outlets dedicating to gulling conspiracy-minded dimwits, and the advent of billions of pocket computers that allow the least knowledgeable among us to communicate with their counterparts across the globe, we are all now engaged in an experiment in the effects of what one might term “elective truth.”

Cavazzoni’s heroes are largely harmless, and most of them antedate the information age. Their charm lies in what the book’s translator calls their “beautifully hopeless enterprise.” The contemporary idiot, by contrast, has abundant reasons for optimism, whether grounded in reality or not. The stupidity that Cavazzoni’s characters pursue in private reveries has become, for them, a collective dream.

Adrian Nathan West is a literary translator, critic, and the author of The Aesthetics of Degradation.