The riot at the Capitol on Jan. 6 is among the uniquely shocking events in U.S. history. Trying to make sense of the senseless, the nation has reminded itself of earlier assaults on the seat of our republic, including the 1814 looting and burning of the building by the invading British. For my part, as I sat watching the horrifying spectacle on television, I kept thinking of the writer Graham Greene.

Sixty-seven years ago, Greene wrote a short story that suggested the combination of anarchy and apathy that seems to catch fire among plundering lawbreakers no matter when or where they emerge.

In “The Destructors,” which first appeared in 1954, Greene described a posse of ill-tempered, ill-mannered lads whose newly anointed leader, T, proposes not only breaking into a beautiful old house but going a step further in their disregard for that which belongs to others. “We’ll pull it down,” T says. “We’ll destroy it.” Armed with nails, hammers, screwdrivers, and chisels, the boys go to work: “The doors were all off, all the skirtings raised, the furniture pillaged and ripped and smashed — no one could have slept in the house except on a bed of broken plaster.” None could enunciate what primordial instinct led them to this point, but they are certain that they won’t be caught. “I’ve never heard of going to prison for breaking things,” one boy says, leading another to answer: “There wouldn’t be time. I’ve seen housebreakers at work.” In his instinct for the heedlessness of criminals, particularly when they work in a group and thus are susceptible to a kind of herd mentality, Greene wrote a story seemingly tailor-made for an era in which property destruction has reemerged with startling vengeance.

Greene’s relevance is something of an open question. In his lifetime, Greene unquestionably profited from writing during and about the Cold War, which is the context and setting for the political and espionage fiction (classic novels such as The Quiet American and Our Man in Havana) for which he was best known. On the other hand, because he died in 1991, just after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Greene’s work has taken on a slightly ghostly cast: He is the sort of novelist one turns to when nostalgic for tales of intelligence officers contending with matters temporal and spiritual in once-exotic locales, such as Cuba, Vietnam, or Sierra Leone, not for help understanding the world as it is today. And Greene’s reflexive anti-Americanism and his turning to figures such as Papa Doc Duvalier for inspiration for his fiction have the slightly moldy air of an issue of Newsweek from about 1965.

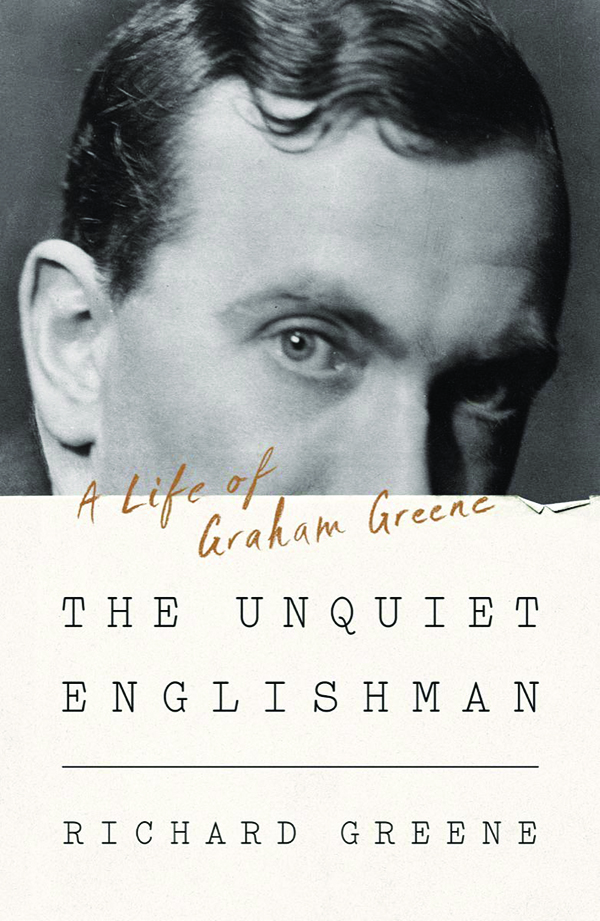

Yet the surprising prescience of “The Destructors” suggests that, for careful readers, there is still much to glean from Greene, which is certainly the verdict of his latest biographer, University of Toronto professor of English Richard Greene (no relation). “Many of his insights into human character and motivation, politics, war, human rights, sexual relationships, and religious belief and doubt remain compelling and provocative,” Greene writes in the masterly The Unquiet Englishman: A Life of Graham Greene. “It is hard to think of a recent writer in English who comes as close to greatness as he does.”

To make his case, biographer Greene recounts the basic contours of novelist Greene’s life, from his glorious tour of duty on the short-lived magazine Night and Day to his formidable forays into screenwriting, including The Third Man (1949), but does so in an engaging, entertaining fashion. The book, fashioned in short, digestible chapters and written in comprehensible prose, has a rare fleetness for a “life and times” work of this sort. Greene’s famous conversion to Catholicism, the faith that would animate so much of his fiction, is described in appealingly practical terms, a matter of necessity if he wanted to marry the woman who became his first wife, Vivien. During his period of instruction with an urbane priest, Father George Trollope, Greene formed a friendship that was as persuasive as any text: “As the sessions — usually once or twice a week — continued, Greene became captivated by the priest himself in whom he detected ‘an inexplicable goodness,’ which in itself became a potent argument for belief.”

Biographer Greene does not romanticize novelist Greene’s stint in MI6, which seems to have been fairly unremarkable in and of itself — “His first, very tiresome task was to produce a large index, known as a ‘Purple Primer,’ of enemy intelligence officers, agents, and contacts in Portugal” — but which certainly enriched his subsequent fiction. In an interview conducted for this book, John le Carre said: “There are people, I count myself among them, who are writers first and everything else second, who go through these strange corridors of the secret world and find an affinity with them, and it never leaves them.”

All of Greene’s life and work seems to be at the fingertips of his biographer, which is all the more astonishing given the novelist’s prolificacy and his wanderlust. For example, it is widely accepted that the basic contours of the plot in Greene’s greatest novel, The End of the Affair (1951), were rooted in his affair with a married convert to Catholicism, Catherine Walston, but the biographer finds the raw material for the story in other corners of his life, including an earlier affair: “So, while the novel is correctly called a roman a clef, the elements drawn from life merely mark out the broad territory in which the act of imagination occurs.” A little-remembered novella Loser Takes All (1955) is said to look ahead to “the comic fiction he would write over the next decade, and, in particular, it introduces numbers as a leitmotif, which reappears especially in Our Man in Havana.”

Biographer Greene’s keen perceptions even help make novelist Greene’s most dated and unpalatable excesses (such as his defense of Kim Philby, the British double agent) at least somewhat comprehensible. Writing about Greene’s views on the Philby affair, the biographer notes: “It was an article of faith for Greene that relationships with individuals were more important than those with countries or societies or groups,” a conviction reflected in one of Greene’s finest late novels, The Human Factor (1978).

Writing appreciatively of his subject’s dashed-off film reviews for the Spectator, the biographer notes, “Indeed, rather like a professional golfer you could not always tell when he was working and when he was playing.” Similarly, this hefty tome has a lightness of touch that is entirely unexpected. “Some people really did read Playboy for the articles,” he dryly writes, referring to Greene’s contributions to the magazine in the late ’60s and early ’70s, and it takes unique imaginative powers to work in a reference to Boy George in a life of the author of The Power and the Glory plausibly. In the end, though, this book demonstrates, as much as the surprising staying power of “The Destructors,” the timelessness of Graham Greene.

Peter Tonguette writes for many publications, including the Wall Street Journal, National Review, and Humanities.