Considering he’d been dead for 143 years, John Adams had a very eventful 1969.

January saw the publication of Gordon S. Wood’s The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787, which famously declared the “irrelevance” of our second president and confined Adams to scholarly obscurity for three decades. About two months later, the curtain rose on a more nuanced, fair, and accurate appraisal of Adams.

Just 47 days separate the publications of Wood’s masterpiece and the Broadway premier of 1776, a musical retelling of the events leading up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence in which Adams serves as the protagonist. Half a century after 1776 portrayed Adams as a hero of the Revolution, Hamilton would revive the reputation of another unfairly forgotten Federalist.

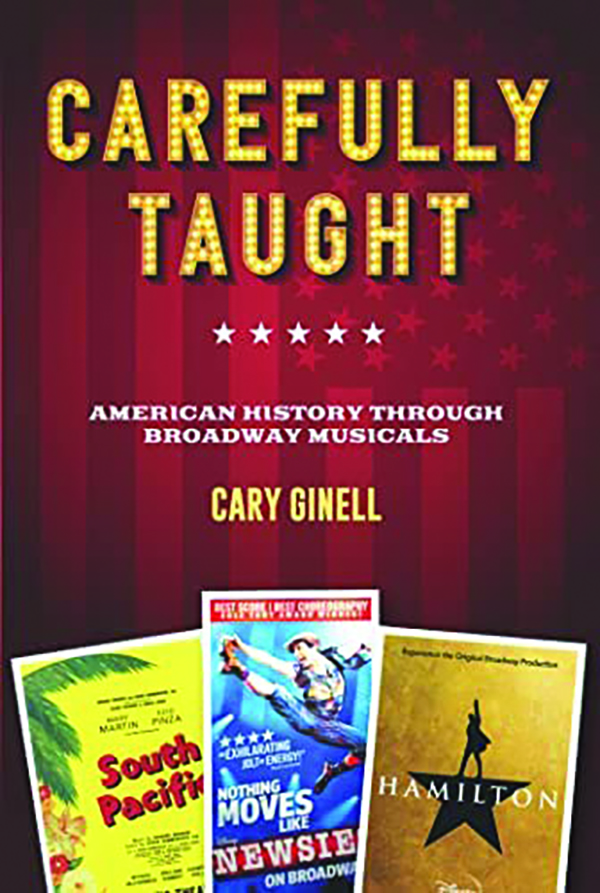

That an institution best known for its fantastical subjects would also produce two shows about the Founding Fathers may seem strange. But the only thing exceptional about these shows is the level of their success. In Carefully Taught: American History Through Broadway Musicals, Cary Ginell shows that the Great White Way has been making musicals about America for nearly a century, essentially setting the nation’s history to music.

Ginell, a theater critic and author, traces a long tradition of historical musicals, including a number of productions likely unknown to all but the most diehard theater buffs. Unfortunately, Ginell functions more as a historian than critic, assembling the record but letting the reader draw their own conclusion. But despite the frustrating lack of analysis, Carefully Taught is an invaluable resource for anyone interested in the history of the American theater or theatrical stagings of American history.

Carefully Taught examines 39 musicals ranging from the American Revolution to the Vietnam War. Each chapter contains a historical outline, production notes, and a discussion of the score. Ginell’s summations are largely free of analysis or opinion, save for the occasional musical commentary.

The shows surveyed include classics such as Oklahoma! and South Pacific, the latter of which boasts Carefully Taught’s titular number. But the book also recounts neglected gems, including 1985’s Big River, a staging of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn with music and lyrics by Roger Miller, who called it “the greatest music I’ve ever written.” Ginell also features some misbegotten shows that are fascinating in their failure, such as Baby Case, a 2012 show about the Lindbergh baby kidnapping in which a cast of 11 played 90 parts.

Occasionally, Ginell’s commitment to highlighting forgotten musicals causes him to make some questionable choices. To mark the birth of rock and roll in the 1950s, Ginell chooses Million Dollar Quartet, the gimmicky tale of a jam session with Elvis and Johnny Cash. It’s a fun show but pales in comparison to Memphis, a show that hits all the musical themes with far better songs and a compelling story about race relations in midcentury America.

Ginell has arranged the book by dramatic date — that is to say, when the shows take place — rather than production date. This structure emphasizes American history over theater history, essentially making the book a U.S. history primer with a particular focus on Broadway musicals.

This may be the logical choice, since a book arranged by production date would seem scattered and chaotic. But it means that the book’s theatrical history is a bit scrambled, jumping from the 1920s to the 1960s to the 2010s all within the first four chapters. Still, while Ginell doesn’t explicitly discuss the chronological evolution of historical musicals, he at least gives readers enough information to draw their own conclusions on this front.

The clearest pattern to emerge is that most musicals about America use historical happenings to comment on current events. Rodgers and Hart’s 1925 musical Dearest Enemy tells the story of Mary Lindley Murray, the wife of a Manhattan Loyalist who, with the help of her daughters, distracted British Gen. William Howe and his troops “with refreshments and comely company” to allow George Washington and the Continental Army to retreat undetected through the city.

Ginell notes that “the story of a brave woman risking her life for a patriotic cause was particularly attractive to the suffragette movement when the musical was staged … only five years after women had been granted the right to vote.” One can imagine a show about women using their feminine wiles to manipulate susceptible men also played well to audiences of Manhattanite women in the midst of the Roaring Twenties.

As the book progresses, the parallels begin to pile up. The same suffragettes who cheered Dearest Enemy were the subjects of Bloomer Girl, a 1944 show by Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg (the duo behind The Wizard of Oz), which was in turn enjoyed by the Riveting Rosies who found themselves wearing the pants, literally and figuratively, while the boys were fighting overseas. In 1961, theater audiences could enter the world of New York’s burlesque clubs in Gypsy, then head nine blocks downtown to hear the tale of the mayor who shut them down in Fiorello!

It’s not surprising that so many musical composers reached for historical plots to comment on their present. What’s surprising is that, unlike Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, the majority of the musicals discussed in Carefully Taught do not use historical allegory to criticize America.

Instead, these shows either celebrate our national past, use history as a jumping-off point to remember what makes us great, or puzzle through how we can improve as a country and people. Even Ragtime, which lays bare the bitter racism and brutal struggles that have marked much of our history, gives us “Wheels of a Dream,” a powerful and uplifting ode to America’s promise.

What explains the theater’s love affair with this republic? Maybe it’s just good content. After all, there’s something dramatic about America. It was there from the beginning, with the Sons of Liberty donning costumes and makeup for the most melodramatic protest of all time. Today, Washington is full of bad actors in every sense of the word. Our conflicts, our triumphs, our heroes — they’re all begging for backup dancers and an 11 o’clock number.

But more importantly, there’s something American about Broadway. Scrappy, Jewish immigrants such as the Schubert brothers built the theaters in the early 20th century, ushering in a long tradition of popular entertainment. Broadway uses popular musical styles to tell relatable stories to Americans rich and poor alike. The Broadway musical is a uniquely American art form, not just because of its style, but because of what it represents.

Broadway embodies what’s best about America — industriousness and vision, free expression and equality. Its songs have mass appeal, and its stories have universal relevance. It’s no wonder, then, that the writers and producers who drive Broadway, despite the liberal politics they boast, have an affinity for America. And it’s no wonder they want to celebrate it onstage.

Today, Broadway finds itself at a crossroads. Hamilton, once the darling of the theater world, has been dismissed by some as insufficiently liberal, which will likely curb its influence on the American theater. Meanwhile, an all-female 1776 currently running on Broadway plays far more patriotic than its directors likely imagined, so much so that one of its stars trashed the production in a Vulture interview this month.

Even in the face of critical pushback and furious actors, producers clearly want to make musicals about America but are increasingly reluctant to make musicals about America’s goodness. Carefully Taught offers an important reminder that there is a long — and profitable — tradition of making shows about our national past.

Tim Rice is associate editor of the Washington Free Beacon.