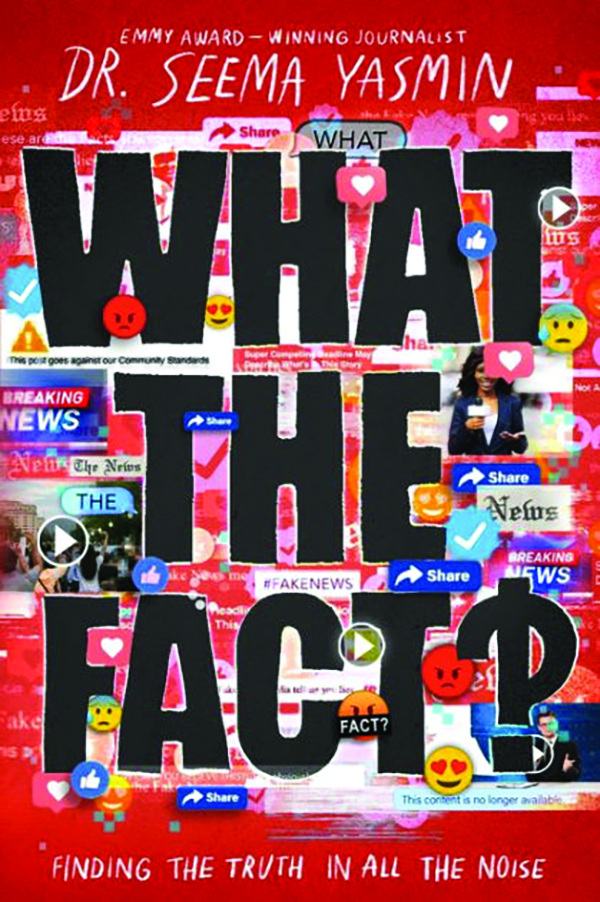

Here’s a story that one often hears about American politics these days: Political conflict is driven by disagreement about facts about the world, and so disagreement stems from false information that is kind of out there, in the air. There’s disinformation, misinformation, lack of context, fake news, conspiracy theories, “alternative facts.” This shifts a great number of political questions into the realm of my academic specialty, epistemology — the study of how we can come to know things. In What the Fact?, Dr. Seema Yasmin offers a chatty introduction to some issues in the psychology and epistemology of politics.

The marketing says this is “a much-needed, timely book about the importance of media literacy, fact-based reporting, and the ability to discern truth from lies,” and the book is subtitled “Finding the Truth in All the Noise.” But What the Fact? is just more noise.

We are emerging from a pandemic caused by a fast-spreading virus. But here’s another fast-spreading virus, Yasmin says: false information. It spreads like wildfire; it’s a contagion. Why do people believe falsehoods so easily? Well, they fit somehow with our “cognitive biases.” At this point, there are really very many essays and books describing the various sorts of cognitive biases that have been posited by psychologists; Yasmin’s explanations offer little novel in the way of charm or clarity, and her discussion is imprecise enough — charitably, let’s say that’s a consequence of trying to appeal to a younger audience — that it may actually be harmful.

What the Fact? is exemplary of a certain unstable progressive consensus on information, though, in how it undermines itself by introducing a political perspective. Yasmin notes: “Not only have scientists been wrong, but they’ve also been racist.” Moreover, “science is not neutral.” To Yasmin, scientists “swim around in uncertainty.” But if science is so uncertain, why is it disinformation to question it or even to believe conspiracy theories about it? Similarly, Yasmin writes that “when journalists claim to be ‘objective’ or ‘neutral,’ what they are really doing is reinforcing the way that things already are.” In its place, she advocates “movement journalism” — a “duty” to “make the world a better place by amplifying the concerns and voices of the most oppressed people in society.” She does her part by adding footnotes about allegedly “ableist” terms and relaying concerns about “minoritized reporters.” But again, it’s not clear why we are obligated to take “movement journalism” very seriously as information rather than propaganda or entertainment.

What the Fact? delights in buzzwords and delineations. For instance, Yasmin differentiates “disinformation” (lies), “misinformation” (unintentionally false information), and “malinformation” (true information that lacks context and thus suggests false inferences). She outlines things like the “FLICC” taxonomy of false information — fake experts, logical fallacies, impossible expectations, cherry-picking, and conspiracy theories. But these sorts of definitions and distinctions aren’t put to much use elsewhere in the text. Rather, they seem to provide a patina of science-y sophistication that falls apart upon closer inspection.

Discussions of neurochemistry are probably some of the best examples. Yasmin writes: “Scientists have found that when you hear moving stories, the parts of the brain involved with emotion light up.” As opposed to what? (Review studies have raised salient questions about whether MRI-ing the brain and seeing which parts “light up” at which stimuli is just a highly overrated method to begin with.) This comes near a section on mirror neurons, a topic frequently mentioned in popular science due to posited connections with empathy and motor learning. But again, those connections are disputed. And after reading Yasmin’s superficial but picturesque account, we might start to wonder whether she is really going to be able to tell us much about how to sift through information with discernment. One paragraph reads simply: “Neurotransmitters! Hormones! Signals! Cortisol! Dopamine! Oxytocin!” Which gives a feel for this section as a whole.

She writes of confirmation bias: “Our brains seek more dopamine, more oxytocin, more information that backs up what we’ve come to believe, while conveniently ignoring evidence that contradicts our beliefs.” Even without the neurochemical hand-waving, this isn’t a great account of what goes on in confirmation bias. Her description of status quo bias is a bit lacking too: “There’s even a status quo bias that argues that humans love it when things stay the same.” A bias can’t “argue” anything. And in any event, this is an odd way to describe status quo bias.

Yasmin’s occasional forays into philosophy were probably the most maddening. Freshman logic students learn that deduction involves following chains of conditional reasoning and moving from the universal to the particular, while induction involves inferring claims about general patterns from observations of specific instances. But according to Yasmin, the difference between deduction and induction is that “deductive thinking relies on facts,” while “inductive reasoning … relies on evidence.” This is not even wrong — I don’t know what she could possibly think she means by this. She offers a decent discussion of the notion of “credence” and the way beliefs relate to actions but goes on, ludicrously, to suggest that the Socratic method is “about adding your perspective to the facts.” She misuses the term “public good,” too, asking, “Is the news a public good, or is it a commodity?” to mean, “Should everyone have access to the news free of charge?” I think Yasmin is trying to seem erudite by using the technical term “public good” here, but she misuses it, and so the effect is the opposite.

What sorts of solutions does What the Fact? offer, and how helpful will it be to what seems to be the intended audience of young adults? Some of the imagery Yasmin comes up with does stick with you — she writes that holding a belief dear, and coming up with arguments to protect it, is like cradling a possum that one takes to be a kitten. That could help a teenager who has never thought about how they form their beliefs do so in a more circumspect way. Overall, though, there are just too many slogans and bromides. “‘Truth’ is about community, and belief is connected to belonging.” “Social agreements have everything to do with power.” The overall picture does not hang together.

The much-touted experts on disinformation and misinformation who have cropped up over the past year or so have become very comfortable with the feeling that disagreeing with them is something between scandalous and criminal. But epistemology, a study of what we can know and what we ought to believe, which goes back millennia, has some less hysterical answers. All of the interesting intellectual meat around these topics has to do with the fact, which I was very pleased to see Yasmin acknowledges, that the same techniques and approaches that could protect good beliefs and attack bad beliefs could also be used to protect bad beliefs and attack good ones — that the opponents of things like propaganda tend to become propagandists themselves. Maybe what that means is that the arguments should really be about what’s right and wrong and about which side should win in politics. But I hate that notion. There are facts about the world, and it is possible to know them. Unfortunately, What the Fact? won’t do much to help you figure out how.

Oliver Traldi is a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Notre Dame.