There’s a throwaway line in Jean Anouilh’s A Waltz of the Toreadors that comes after the play’s central character, a jaded belle epoque general, complains about what hopeless frumps his two daughters are. When his naive young aide-de-camp replies that the girls have many good qualities, the general concedes as much but laments that they’re all the wrong ones.

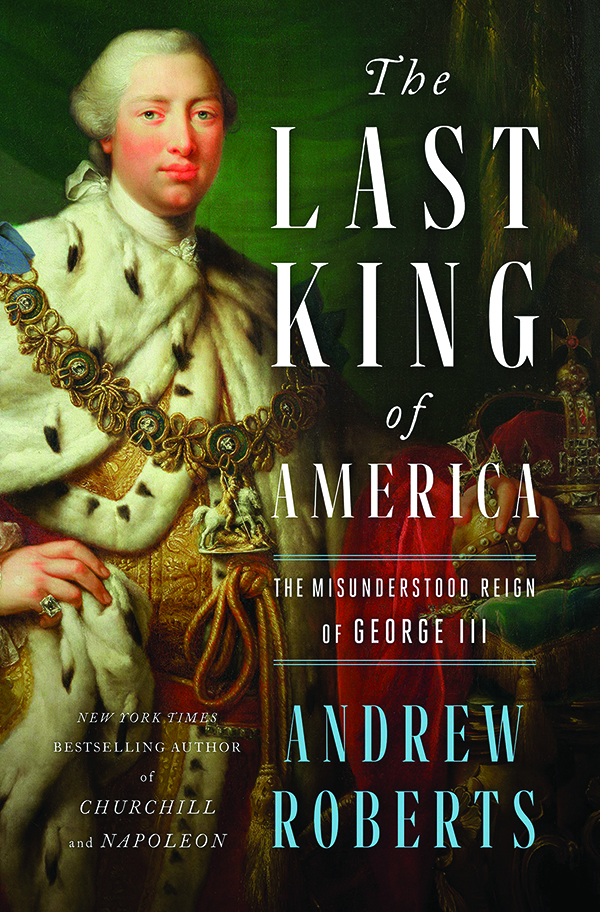

Much the same thing could be said for poor, long-suffering King George III. As historian Andrew Roberts amply demonstrates in his new biography, The Last King of America, George was a man of many personal virtues — he was kindly, conscientious, cultured, sincere, and scrupulously honest — and morally upstanding in both private and public life. He also had a strict sense of honor and an intense commitment to his duty to serve his subjects as a wise, just, and patriotic king who stood above the corrupt factional politics of 18th-century Britain.

Admirable qualities all, but, as Roberts shows, none of them equipped this mentally fragile man to succeed to the throne at the age of 22 after a traumatic, secluded childhood and to reign in the midst of a costly global conflict, the Seven Years’ War, that saw British armies fighting on four continents and the Royal Navy ruling the waves in every quarter of the globe. George was also fated to wear his crown for a long time, from 1760 to 1820. Only Queen Victoria and her great-great-granddaughter, Elizabeth II, would serve longer. Unlike George, neither of the ladies would spend large chunks of their reigns certifiably bonkers and under varying degrees of restraint.

In his own lifetime, and over the centuries that followed, George III has received a lot of bad press, including some rhetorical overkill in the Declaration of Independence courtesy of Thomas Jefferson, whose Francophilia was exceeded only by his Anglophobia. Roberts shows that George, far from being the bloodthirsty tyrant of Jefferson’s lurid prose, was a well-intended monarch with limited personal powers who tried to resolve the friction between his American subjects and the British government through an admittedly erratic mix of conciliatory gestures and military force.

The fact is that during the American Revolution, approximately equal numbers of colonists took up arms in support of and in opposition to the crown, while most Americans sat by passively awaiting the outcome of the struggle. This fact, which persisted in the face of British ham-handedness and brutality on both sides, demonstrates the strong residual loyalty many Americans felt toward the British crown throughout the war. Nor did Britain come out too badly. While the loss of the 13 colonies was a blow to its prestige, Britain remained the world’s preeminent naval power and the owner of a global network of colonies that far outstripped those of any of its European rivals. And the later years of George’s reign would see Britain defeating Napoleon and ending France’s dominance of continental Europe forever while leaving it a poor runner-up in the scramble for overseas power.

All in all, not a bad run. Indeed, in the words of English historian Geoffrey Treasure, “It was a great reign. But George III was in no sense a great man.” During the last 20 years of his life, George was virtually absent as a ruler, and during the last decade, “he was irremediably mad.” His heir and, after 1812, regent, who would become George IV upon his father’s death in 1820, “was so unpopular that it was uncertain whether monarchy would survive at all.” It did, but in a limited form, and that thanks largely to the skillful maneuvering of Queen Victoria.

For all his flaws, George III was a good man struggling to be a great man. He has finally found an able, articulate apologist in Roberts, whose earlier biographies of Napoleon and Winston Churchill received much well-deserved acclaim. If there is a fly in the ointment, it is the fact that, while Roberts has tackled his latest subject with the same wit, grace, and erudition he brought to his last two biographical subjects, George III was no Churchill, and certainly no Napoleon. One suspects that some of those who read Roberts’s massive tomes on those two historical giants may be less keen to trek through 758 pages of sometimes excruciating detail about the life and times of the dutiful but demented king, especially when much space is taken up with details on, for instance, the cost of the gold and porcelain plates of which George dined for his 25th birthday.

Still, those readers who do make it to the finish line will probably concur with the author’s view that, as man and monarch, George III was not the “cartoonish pantomime villain” depicted by everyone from Jefferson to Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda but rather one of the most tragic monarchs in British history, as well as “the most underestimated and misunderstood.” This reviewer certainly did.

Aram Bakshian Jr. served as an aide to Presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan. His writing on politics, history, gastronomy, and the arts has been widely published here and overseas.