In the 1920s, Buster Keaton made some of the greatest silent film comedies and just plain some of the greatest comedies, ever. But most of his sound-era films are barely watchable. His creative and personal decline grew out of the failure of his first marriage, his struggles with booze, and the loss of creative control per his MGM contract. This has long been known from the evidence we can still see on our screens as well as from the horse’s mouth, since Keaton spoke freely to biographers and the press for decades before his death in 1966. There is thus seemingly little new ground to be plowed for a Buster Keaton biography or critical study in 2022.

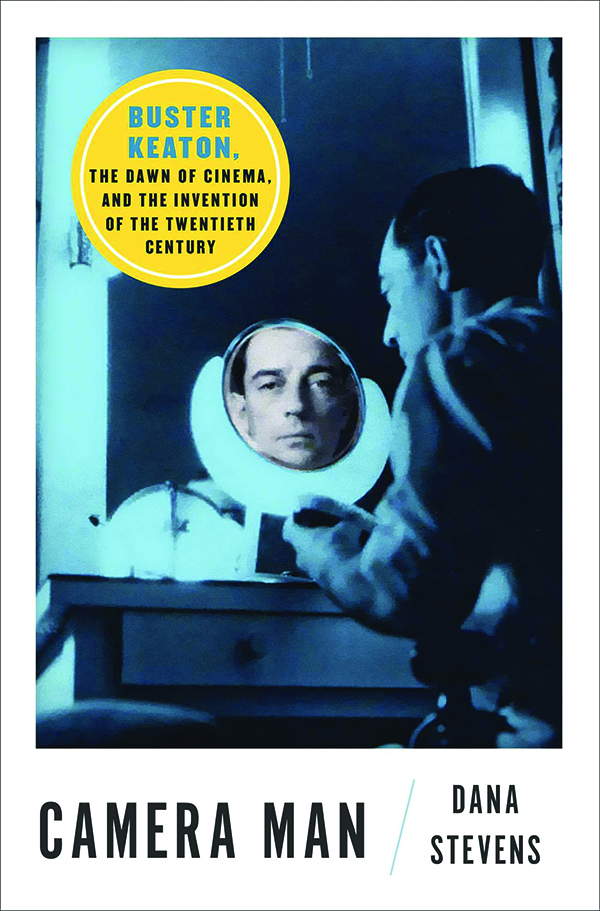

In Camera Man, Dana Stevens doesn’t try to plow that kind of new ground, but she does find a fresh angle in her subtitle: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century. Her ambition is to make Keaton a century-defining man, his life paralleling key moments and movements of the 20th century, his work reflecting them and influencing them back. At the most obvious level of biography, he began in vaudeville as a toddler from the early 1900s, transitioned to the movies in the late 1910s, and rediscovered himself on TV in the 1950s, reflecting broader changes in America’s own entertainment habits. Keaton was well fitted for each new medium. In a less obvious mode, film criticism grew up around Keaton. The man Stevens identifies as America’s first real film critic, Robert Sherwood, was an early champion of Keaton in the pages of a then-new outlet called Life magazine. And Life will appear later, in the person of James Agee, in reviving the reputation of Keaton and other silent comedians. Even movements that don’t seem to be connected to Keaton, such as Bloomsbury, Stevens paints as different reactions to the same reality.

It’s fascinating and engaging how many different directions Stevens goes in, and she ends every chapter with a teasing cliff-hanger and/or an adept turn of phrase. But there are times it doesn’t quite work. For example, what kind of 20th-century story barely mentions World War II as an event? A conventional Buster Keaton biography might, since he played no active role in it. But this one? You also do start to notice the use of the hypothetical and speculative voices and of rhetorical questions when Stevens tries to draw connections between people and places — Theda Bara and Georges Melies drew my biggest “huh?” reactions — that, as far as she and we know, had no actual connection at the time, using phrases like, “Buster had to have seen this-or-that film” or “You can imagine Buster and So-and-So crossing paths.” But then, Camera Man is a book about coinciding that makes you think there might be more than mere coincidences.

Camera Man is a fast and pleasurable read, blessedly free of both incomprehensible film-studies jargon and the worst of 2022 wokeness. Stevens is like a garrulous and loquacious friend whose tendency to go off on tangents you forgive because the tangents are usually interesting in their own right (see three pages on the history of Childs Restaurant) and because she always finds her way back to the subject. She also continually embraces “both/and,” a sure sign of a good critic. She unpacks, for example, the ambivalent relationship an audience has toward dangerous stunts involving a child during an era of child welfare legislation. In a similar vein, she notes that Keaton’s first short films, made in the late-’10s with Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, are “weird documents, feverishly energetic and cheerfully perverse,” containing both “cruelly retrograde ‘jokes’” and “filmic innovation.“

Speaking of the view from the morally self-righteous yet unmoored moment that is 2022 wokeness, it might be noted that Stevens is the chief film critic at Slate. Founded by Microsoft in an office shared with the American Enterprise Institute, it has devolved into a clearinghouse for intellectually and culturally obtuse nonsense (cf. February 2022’s “When an Eating Disorder Collides with Climate Activism”), with some great writing still mixed in vestigially. That makes it all the more pleasant to find that there are no “Slate pitches” here. Stevens is a liberal, and that can be determined at times. But like Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris, and Roger Ebert until almost the end, Stevens isn’t in-your-face or performative or acontextual about it and doesn’t take 2022’s cheapest and easiest paths (except maybe on Mabel Normand). But, in just one example, she doesn’t go too far into queer theory when discussing Keaton’s and Arbuckle’s frequent (and often hilarious) cross-dressing gags. Thus Camera Man (and Stevens’s fine work in general) is profitable even to people who don’t share her ideological views.

For example, there is a whole chapter on Keaton’s frequent use of blackface and other racial humor. That he used this vaudeville trope is undeniable and unavoidable, and Stevens condemns it. But two other things distinguish this chapter — one positive, one negative. Stevens doesn’t breathe a word against The General as Confederate nostalgia, as we might half-expect today. She also devotes a large part of this chapter to the unsung career of Bert Williams, a Bahamas-born stage actor whom Keaton admired and cited and who was one of the first black performers on Broadway. Williams’s use of blackface and his typical character is both analyzed and contextualized, and the similarities and (obvious) differences to Keaton’s use of it, especially including specific details in College, are teased out.

Other chapters work on similar terms, using Keaton and synchronous parallels between key moments in his life and related lives. The chapter on Keaton’s alcoholism devotes considerable space both to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Alcoholics Anonymous. The former was in Hollywood trying to find work in between benders and bottles and the latter was being founded at the same time Keaton himself was hitting rock bottom.

There is no evidence that Keaton ever had anything to do with either, and Stevens acknowledges that he was not the AA type and would always be “a dry drunk” in its terminology. Walking down Buster Keaton’s funny and tragic life path offers Stevens a chance to peer into so many alternate lives, the many people he influenced, and often the many examples of who else he may have been. The road not taken is strewn with lamps that illuminate the life Keaton did live.

Victor Morton is a film writer living in the Washington area.