There are, or were, before assorted 20th-century innovations, broadly two kinds of lyric poetry: the poetry of exaggeration (of the virtues of the poet’s beloved, of the depths of his own sensations) and the poetry of precision, which looks for words sufficiently rigorous to make emotional states graspable objects of thought. Often, the two are mingled, and we easily confuse them, because there is no firm criterion by which to measure strength of feeling and thus to calibrate the figurative language best suited to us. How to get this right was the guiding question of the work of Paul Valery, who strove, for much of his life, to organize emotion into a system that offered access to higher truths about himself.

Valery was one of the last of the writers in the Goethe mold — a man aspiring to universal knowledge, who hoped to bend science toward the vaguer ends of art while subjecting artistic practice to scientific discipline. He is thought of mainly as a poet, but verse was a small part of his output, which included essays on epistemology and architecture, meditations on Leonardo da Vinci, and 30,000 pages of notebooks that many scholars consider his masterpiece. Attention to him in English has come and gone over the years; his early Anglophone reviewers, most notably Edmund Wilson and T.S. Eliot, generally read him in French.

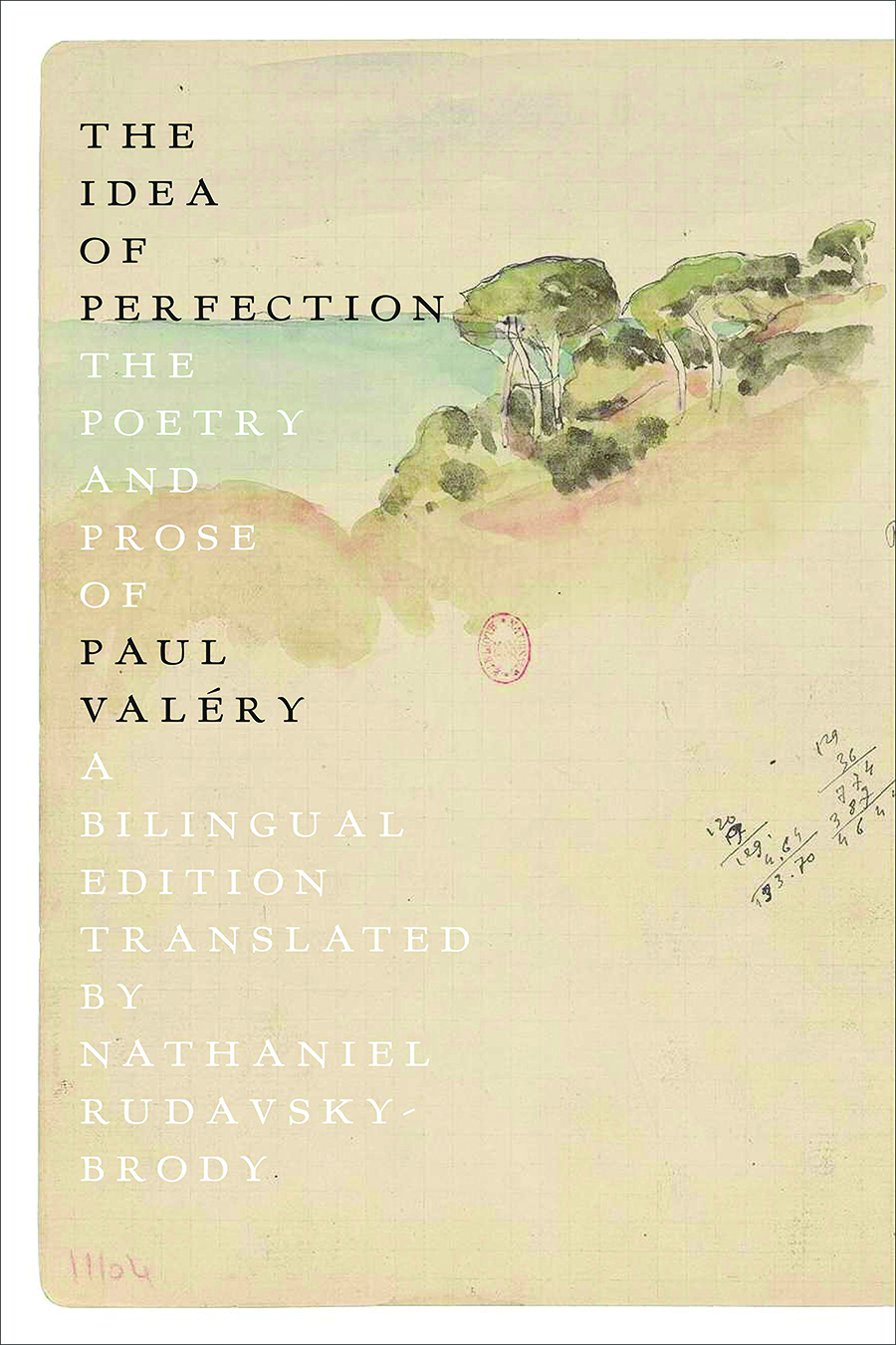

The Idea of Perfection, a bilingual anthology of poetry and prose with an intelligent introduction by translator Nathaniel Rudavsky-Brody, is a gratifying affirmation of Valery’s central place in 20th-century literature. Rudavsky-Brody is a poet, and his emphasis here is on Valery’s poetry.

Nominally, The Idea of Perfection covers 50 years of writing, from 1890 to the author’s death in 1945, but this is only true in part. Valery experienced a crisis in 1892, shortly before his 22nd birthday, and left off writing poetry for two decades; his Album of Early Verse, which he published in 1920 at the prompting of Andre Gide, revised the writings of his youth heavily to bring them in line with his developing ideas. He seems to have suffered from an unrequited infatuation with an aristocratic widow nearly twice his age, but he depicted his breakdown in transcendental terms, as the drama of an unworthy soul struggling with its vital calling, one requiring an abandonment of long-held principles and the forging of a new self.

This preoccupation with the conflict between sensuality and the mind was an old one, but, in Valery’s case, it was muddied by two intuitions: first, that there are sensual truths inexpressible in intellectual terms, and second, that understanding may not be an act of grasping the world but a kind of inborn disorder the poet must struggle to escape. As he wrote in Monsieur Teste:

If there is a governing metaphor across Valery’s work, it is perhaps Narcissus, who provides a curious, not entirely wanted persona for the poet. For Valery, all consciousness is self-consciousness, with the anxiousness that implies, and his Narcissus, faced with a mirror image he knows to be a mere appearance, is a metaphor for the artist’s inability to achieve unity with his work. The theme first appears in 1891’s “Narcissus Speaks,” and Valery would revisit it in “Fragments of Narcissus” (from 1921’s Charms) and in a “Narcissus Cantata,” the last of these absent from The Idea of Perfection.

Its most affecting treatment is in the late prose poem “The Angel,” which closes the book. Here, an angel peers into a fountain and sees reflected the face of a man, his features “inadequate to the universality of his own limpid knowledge.” The angel is unable to recognize his perfection in the sorrowful creature who looks back at him. At last, after a lifetime seeking after purity, Valery sees it looking down on him through the fluid blur of knowledge and sensation and finds the ideas that embody it as indifferent to him as he is incapable of discerning them: “Were he to disappear, it seemed that the system, sparkling like a crown, of their simultaneous necessity, might continue to exist alone in its divine fullness.”

Translating poetry is a dicey business. I say this from experience. You serve not two masters but a minimum of five: the sound and sense of the original, the sound and sense of the English version, and that clutter of linguistic artifices that distinguish a text from prose. As John Dryden put it: “‘Tis much like dancing on Ropes with fetter’d Leggs: A man may shun a fall by using Caution, but the gracefulness of Motion is not to be expected.” Formal strictures make matters worse, and Valery was, formally, a conservative poet. He claimed that only God had a right to harmony of thought and gesture, while mortals must endow their art with “the qualities of a resistant material” — i.e., meter and rhyme. Rudavsky-Brody’s versions, most of them in blank verse, tread a reasonable balance between respect for meaning and form, and occasionally his lines (“A pregnant plenitude of silent thoughts” or “Pour out profusions of our silver tears”) are more striking than their French originals.

If Valery is frustrating, it is because he gives a feel of intellectuality but offers, in place of ideas, intellectual sensations. In a letter to his patroness and translator, Natalie Clifford Barney, he claimed he had been profligate with ideas but faithful to none. Barney herself felt he was not a true poet because he didn’t believe in love, and there is something weirdly chaste about much of his verse, as though figurative language were an impediment placed deliberately between him and the objects of his longing. Nonetheless, he remains there, a deity in the French pantheon, and anyone interested in symbolism and its influence on European letters will find a reading of The Idea of Perfection worthwhile.

Adrian Nathan West is a literary translator, critic, and the author of The Aesthetics of Degradation.