Every week, I wait with bated breath for Saturday to roll around. Not so much the day of the week, although as an observant Jew, I cherish the time and space for family, prayer, and community that the Sabbath affords. No, I mean the New York Times Saturday crossword puzzle, the most challenging one of them all, the puzzle so deviously hard that the late actor Paul Sorvino once rather politically incorrectly labeled it “the bitch mother of all crosswords.” The Saturday puzzle runs me through the wringer of emotions: consternation, annoyance, anger, hope, and, eventually, satisfaction. The ultimate reward is not the destination of a finished grid but the hard-fought journey from confusion to completion, along with the many lessons learned along the way.

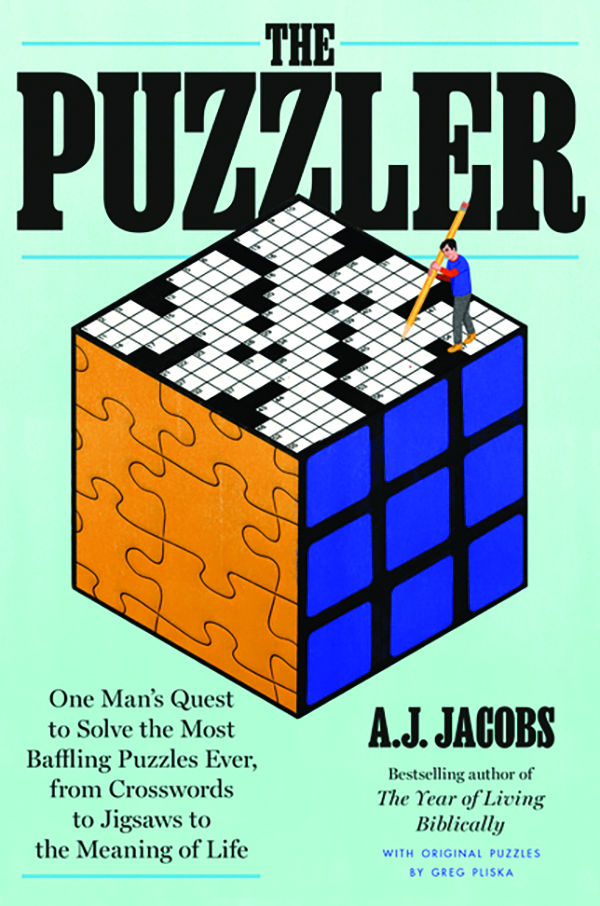

Upon this journey embarks the journalist and writer A.J. Jacobs in The Puzzler, his sparkling, time-consuming voyage into the world of puzzles, why they matter, and how the process of converting befuddlement to delight improves us personally and intellectually. He argues convincingly that “doing puzzles can make us better thinkers, more creative, more incisive, more persistent.”

For brevity, it’s hard to improve on the formula of Japanese puzzle-maker Maki Kaji, which Jacobs quotes and wholeheartedly endorses: ? → !

(In English: “bafflement, wrestling, solution!”)

But as Jacobs traverses the wilds of crosswords, rebuses, chess problems, logic puzzles, labyrinths, jigsaws, cryptics, sudokus, Spelling Bees, KenKens, and many others, he aims higher, determined to prove how puzzles “nudge us to adopt the puzzle mindset — a mindset of ceaseless curiosity about everything in the world, from politics to science to human relationships — and a desire to find solutions.”

Jacobs illustrates his journey with examples — many of them. Each chapter on a given puzzle type concludes with an appendix containing sample puzzles of that type that can be completed in the book itself. And following his final chapter, he includes a devilish “puzzle hunt” comprising every type of enigma he explores. He even offers a $10,000 cash prize for the first finisher. Completing these bonus puzzles, with help from family members, grievously set back my efforts to review the book but greatly enriched my enjoyment of it.

Among the many lessons Jacobs gleans from his puzzle-thon, perhaps the most important is what he calls “the way of the eraser.” When completing a crossword puzzle, always use pencil, and don’t succumb to embarrassment over erasing your errors. This mindset, i.e. “being okay with mistakes, okay with tentative beliefs, okay with flexibility,” enhances not only our ability to solve thorny problems but to engage with others inclined to solve them in alternative ways. If we approach the world and its many challenges with less certainty and more optionality, we are more likely to encounter success in confronting those obstacles. And while I personally prefer to complete crossword and other puzzle grids in pen — go big or go home! — I’m never above crossing out wrong answers and changing my mind.

Jacobs also enjoins his readers to embrace algorithmic thinking, but within reason. He overcomes his lifetime aversion to the Rubik’s cube, which, with 450 million units sold, likely represents the world’s bestselling puzzle, by training over Zoom with Sydney Weaver, a renowned Rubik master, and interviewing a Frenchman who designed a 33 x 33 x 33 monster, the world’s largest. He concludes that the application of organized, step-by-step guidance can convert even a novice into a Rubik’s genius, or transform a seemingly complex problem into a solvable one, by bringing order to the chaos. But this approach isn’t always possible, Jacobs concedes: “I have come to accept that sometimes life is disturbingly chaotic and unpredictable.”

Puzzles also teach us to embrace “those wise restraints that make us free,” as the early 20th century legal scholar John MacArthur Maguire famously described the law. Take Spelling Bee, the virally popular New York Times daily puzzle that offers six letters in a hexagon surrounding a seventh, requiring participants to make words of at least four letters that use the center letter and at least one word using all seven. “Constraints lead to creativity,” Jacobs posits, and the Spelling Bee’s minimal rules unlock maximal possibilities.

Teamwork, too, both spurs and results from successful puzzling. In an especially amusing chapter, Jacobs schleps his wife and tweenage sons to a jigsaw tournament in a Spanish town outside Madrid, where they represent the United States. Their mission: to complete four 1,000-plus-piece Ravensburger puzzles in eight hours, all while wearing corny dad-joke T-shirts he designed reading “E Pluribus Unum Pictura.” Spoiler alert: The Jacobses don’t win, but they also don’t finish last. And while they find plenty of frustration along the way, as those of us who completed dozens of such massive puzzles during the pandemic can attest, their family developed a sense of camaraderie and cooperation that elevated their individual efforts into more than the sum of their parts.

This spirit of comradeship speaks to me, too. Few pleasures top solving a themed New York Times Sunday puzzle with my wife, a staple since we began dating more than 20 years ago — incidentally, my wife, in this as in all things far more diligent than me, has worked backward through historic New York Times puzzles on the crossword mobile app and now finds herself returning to 1993. Many an airplane trip has been occupied by completing KenKens and crosswords with our children, and when we visit my parents in California, we huddle around the radio (yes, the radio) on Sunday mornings to listen to the weekly NPR word puzzle. And since moving to Israel, our family inaugurated a new tradition of tackling the weekly 20-question trivia quiz published in the Haaretz newspaper.

But puzzles also contain a certain countercultureness or monasticism: In a world full of infinite possibilities, we appreciate the singularity of a solution. “Life is a puzzle,” Jacobs’s hero, Peter Gordon, a New York Times crossword contributor and the creator of the fiendishly difficult weekly Fireball Crossword, tells him. “Who should you marry? That’s a puzzle. What job should you take? That’s a puzzle. With those puzzles, it’s hard to know if you got the best answer. But with crosswords, there is one correct answer. So that’s comforting.” Jacobs unlocks one such impossible challenge: a 19th century rebus that only two other people had previously solved — one of whom, Will Shortz, the longtime New York Times puzzle editor whom Jacobs also visits, applauds the author’s persistence.

I feel this way not only about crosswords but also escape rooms, of which our family has completed several dozen on four continents. Here, as with jigsaws and other collaborative efforts, after plenty of snapping and grabbing and yelling, we proceed methodically from one step to the next in search of the one ultimate solution. With all of the distractions represented by our smartphones locked away in a cabinet outside, we’re free, for an hour or less, to focus solely on a series of tricky but solvable problems demanding our full attention and mental acuity.

Along his journey, Jacobs experiments not only with solving puzzles but with creating them. He absorbs crossword tips from Shortz and Gordon, he assists his wife’s company in developing a puzzle hunt for corporate clients, and he even devises a “generation puzzle” — akin to the classic Tower of Hanoi, with a stack of disks that must be moved across three rods without placing a larger disk atop a smaller one. But Jacobs’s generation puzzle, which he dubs “Jacobs’ Ladder,” requires more than a decillion (the number one followed by 33 zeros) steps to solve. Even at the fastest pace humanly imaginable, the universe will have entirely decayed by the time it’s completed.

All of this tends to raise the kinds of profound philosophical questions we sometimes encounter in our most contemplative moments: Why bother? What’s the point? If the work can never be finished, why start in the first place? Perhaps the importance of puzzles pales in comparison to the deeper mysteries of life, but the dynamic is the same: In both contexts, we strive to learn, to achieve, to improve, to resolve because the effort itself is what makes us human. Puzzles, like life itself, expose our shortcomings and inspire perseverance.

Jacobs concludes by invoking the wise words of renowned lyricist and avid puzzler Stephen Sondheim: “A good clue can give you all the pleasures of being duped that a mystery story can. It has surface innocence, surprise, the revelation of concealed meaning, and the catharsis of solution.” This charming book provides all of the above — and then some. Now, if only Saturday would arrive more than once a week.

Michael M. Rosen is an attorney and writer in Israel and an adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.