The curious fate of Truman Capote’s final, unfinished novel is typically thought of as a cautionary tale of the perils of writers becoming too cozy with, or dependent upon, their subjects.

Capote’s endlessly discussed, perpetually delayed, self-described “magnum opus,” Answered Prayers, was intended as the cafe society equivalent of the author’s 1966 “nonfiction novel” In Cold Blood: a book that marshaled the tools of fiction, as well as Capote’s unerringly elegant way with words, to recount actual events — gossipy anecdotes, really — that the author had heard about. But when excerpts from Answered Prayers began to emerge in dribs and drabs in magazines in the mid-1970s, a slew of Capote’s unwitting sources, including high-society staples Babe Paley and Slim Hayward, were outraged at having their private lives exposed.

Wounded by being cast out of a social set he cultivated, Capote let Answered Prayers molder. A man of manifold bad habits and addictions, Capote either lacked the dedication or, more likely, the killer instinct to complete the novel, which was unpublished at the time of his death, at 59, in 1984. Three years later, the extant fragments were at last put between hardcovers. It turned out that Answered Prayers was a perfectly credible parody of the privileged classes, albeit one that was relatively toothless when compared to another New York satire published in 1987: Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities.

In fact, Capote’s reluctance to pull the trigger on Answered Prayers seems, in retrospect, to have been remarkably short-sighted. Although Capote was clearly beside himself at being cut loose by some of his fancy friends, he should have recognized that literature, if that’s what he thought he was creating, was likely to last longer than friendship. Not only are all of the “swans” whose dirty laundry Capote aired now deceased, but that same laundry is once again flapping in the wind.

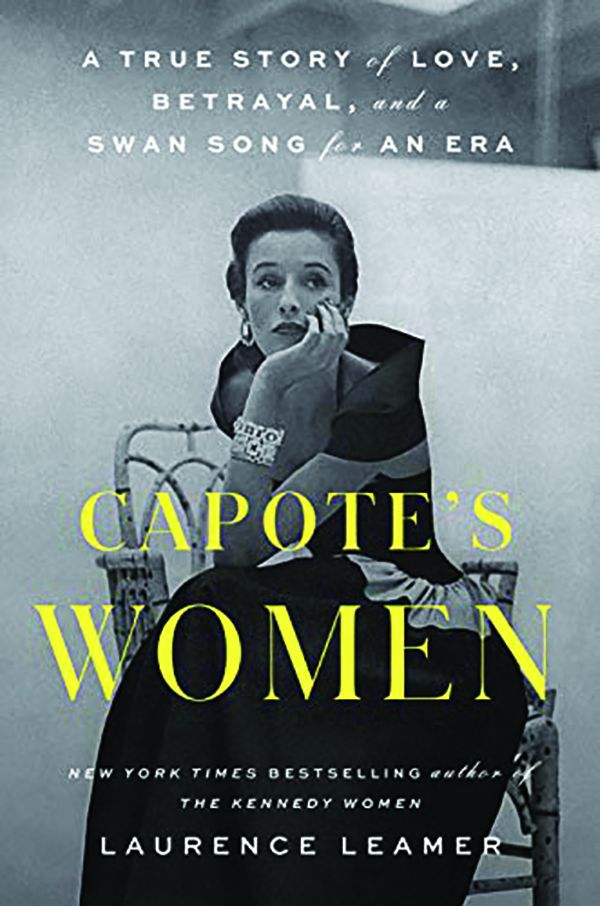

In a new book about Capote’s friendship with the haut monde, author Laurence Leamer dives into the lives of the women who bewitched Truman with considerably more detail, and far less writerly aplomb, than anything contained in Answered Prayers. And Leamer names names.

Ironically, given the rather trashy tone of Capote’s Women, Leamer makes clear that Capote’s intentions in writing Answered Prayers were relatively pure or, at least, respectably literary. In 1958, frustrated by the relative flimsiness of his bibliography to date — which, by then, included the reed-thin novels Other Voices, Other Rooms, The Grass Harp, and the soon-to-be-published novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s — Capote resolved to produce a more substantial novel, a book that summoned the swanky milieu he had been traveling in. He looked to Proust as a model.

“The novel is called, ‘Answered Prayers’; and if all goes well, I think it will answer mine,” Capote wrote in a letter to Random House publisher Bennett Cerf. That he risked estranging women whose friendships he coveted seems to have mattered little. After his biographer Gerald Clarke warned Capote that he had barely managed to conceal his fictional characters’ real identities, the author snapped back: “They won’t know who they are. They’re too dumb.”

But along with Capote’s apparent seriousness of purpose was his equally serious appetite for the lifestyles he sought to send up. Like his mother Lillie Mae, described as a Southern social climber, Capote was drawn to his swans like a moth to a flame. “Truman loved to be around women,” Leamer writes. “Women were more intimate, more self-aware, more observant, more concerned with the details of life in the same way he was.” He adopted worshipful tones in speaking about them, describing Paley as “the most beautiful woman of the twentieth century” and commemorating his first encounter with C.Z. Guest this way: “Her hair parted in the middle and paler than Don Perignon, was but a shade darker than the dress she was wearing, a Main Bocher column of white crepe de chine. No jewelry, not much makeup; just blanc do blanc perfection.”

Leamer rather lurchingly switches between biographical portraits of assorted swans with passages about Capote, especially his relationships with them and his mining of material from them. Referring to his tete-a-tetes with Pamela Harriman, Capote said, “We spent a lot of time on yachts together. Anybody becomes a confidant on a yacht cruise, and I think I’ve lived through every screw she ever had in her life.” Yet Leamer is no Capote: The affairs, extravagances, and excesses described here tend to run together, forming a kind of collage of naughty behavior among the well-to-do. Only the reader steeped in this social set can keep track: Slim Hayward did what? C.Z. Guest said what? Pamela Harriman set her sights on whom?

Even worse, Capote’s Women fails to capture, as does, in its way, Answered Prayers, what drew Capote to these women in the first place. While he surely relished their gossip, Capote was also genuinely charmed by America’s beautiful people. And to the extent that figures such as Paley still intrigue us, it’s not for what they might have done behind closed doors but for the cool, gracious way they presented themselves, passed their time, and furnished their homes. But if lifestyles of the WASPy and refined is what you’re after, a book of pictures by Slim Aarons will do just fine.

Maybe Capote was right to give up on Answered Prayers after all. In the end, that book, like this one, says at length what Fitzgerald said in a sharp, quick line in The Great Gatsby: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy — they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that held them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Peter Tonguette writes for many publications, including the Wall Street Journal, National Review, and the American Conservative.