Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) had an inauspicious beginning for a Founding Father. Born on Milk Street in Boston, Massachusetts, to a working-class family, he was the youngest son and one of 17 siblings and step-siblings. His father lacked the money to educate him.

But Franklin had a robust sense of irony and a way with words that bordered on poetry. He bought one of the leading newspapers of the colonies, the Pennsylvania Gazette, which he printed and contributed to and which covered events in America and Britain. He also compiled Poor Richard’s Almanack beginning in 1733, which sold more than 10,000 copies a year and made him rich. His other book, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (1791), written to inspire his son, William, became a classic and is widely read today.

REVIEW OF KING: A LIFE BY JONATHAN EIG

Franklin was a leading figure of the Enlightenment. He founded schools, libraries, and hospitals. Self-educated, he was an inventor, a respected scientist, a community leader, and an internationally regarded statesman and educator. He would serve as a delegate to the Continental Congress and help Thomas Jefferson and others draft the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution.

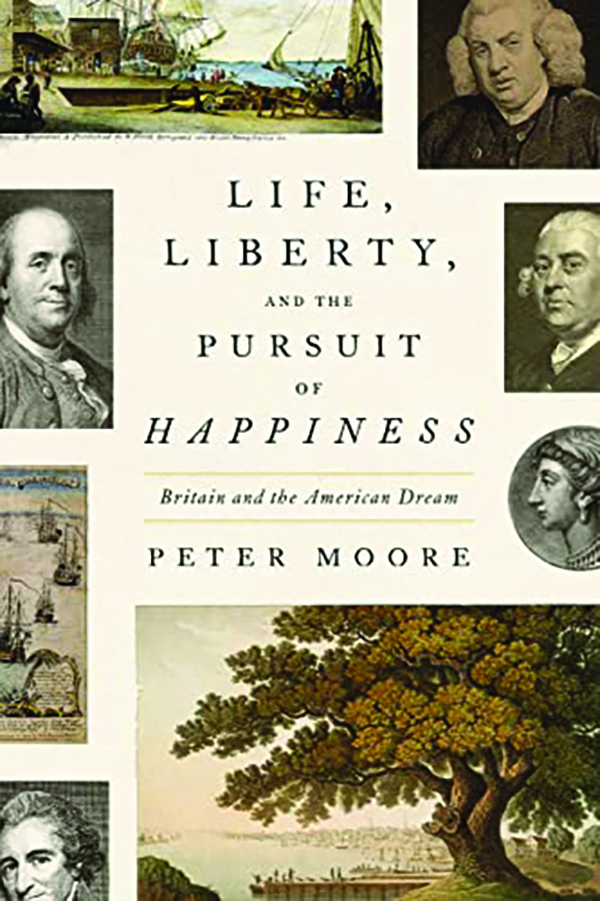

Franklin is the central character in Peter Moore’s new book, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness: Britain and the American Dream, which chronicles the lives of Franklin and five of his British contemporaries who set the stage for the Declaration of Independence.

A British historian, Moore teaches at the University of Oxford and specializes in 18th-century history. His book offers a well-researched and brightly written account of life in England and America from 1740 to 1776.

The highlight of the book for American readers is the way Moore showcases the British perspective detailing what happened in Britain during the buildup to the revolution. He describes the political and financial tensions as well as the views of those who supported the colonies and those who did not — with Franklin almost always in the middle.

Moore interweaves two stories. One is that of Franklin’s rise from obscurity to the heights of diplomacy, including the friends and enemies he made along the way. The other is that of the declining relations between England and America, mainly over money issues. The bottom line might be Franklin’s maxim: “If you would know the value of money, try to borrow some.”

The Seven Years’ War between Britain and France had triggered financial strain for Britain, as Moore explains. It also raised problems that disrupted relations between George III and Parliament, setting off dissension among members of Parliament. Britain had helped the colonists survive and protected them from the French. The colonists were British citizens and were expected to pay their dues when Britain reached out for financial aid. Many were born in England and had families residing there. Although happy when the Seven Years’ War ended, the colonies had their own money woes and rebelled against any increased financial burdens.

Their rebellion led to the Boston Tea Party, when 342 chests of tea were thrown from ships into Boston Harbor, to the Revolutionary War (1775-1783), and to the Declaration of Independence (1776), the wording of which was influenced by the six people featured in Moore’s book.

Each held opinions regarding the tensions between the two countries. Franklin at first sided with Britain but then became an American patriot. He had roots in both nations.

He spent years in London and established long-standing friendships as well as business and political connections. These contacts included Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), William Strahan (1715 -1785), John Wilkes (1725-1797), Catherine Macauley (1731-1791), and Thomas Paine (1737-1809).

Franklin was especially congenial with the London writer, printer, and publisher Strahan, whom he had mentored. Strahan sided with Britain, calling the colonists “obstinate madmen,” and supported the Intolerable Acts to force the colonies into submission. Franklin, at first, agreed with Strahan but changed his mind when he became convinced of the corruption in Parliament. Moore focuses on their differing political views and how they adversely affected their friendship.

It didn’t help that Franklin forwarded letters that expressed negative opinions on the colonies’ ability to govern themselves. He had wanted them to be kept confidential, but once they were out, they were leaked, and they lit the fuse for the Revolution. (“Three can keep a secret if two of them are dead,” as Franklin himself once put it in a maxim.)

Slavery also ratcheted up tension between England and America and influenced the views of the principal characters. Paine’s hatred of slavery led him to the idea that all men were created equal. Moore also mentions that Samuel Johnson, the lexicographer, treated Francis Barber, the slave he inherited, like a son, and left his estate to Barber.

Paine thrived on the notion of free speech. He was uneducated and started out as an “inconstant, ill-omened” person. But when he met Franklin, his life changed. He asked Franklin for and received a recommendation, traveled to Philadelphia, found work as a writer and editor for a new magazine called The Pennsylvanian, and soon became a statesman as well as the author of Common Sense, which inspired the Revolutionary War and the Declaration of Independence.

Macauley lobbied for women’s freedom. She believed that women had a right to an education and to live freely pursuing their own goals. Not allowed to go to school, she had studied in her father’s extensive library, formed opinions, and shared these via her articles and books.

She became close friends with Founding Father Samuel Adams and sided with the colonists against England. She argued that if the colonists broke away, Britain would have only “the bare possession of their foggy islands.” She openly disagreed with Samuel Johnson, who saw the colonists as “excitable, restless, and inconstant people,” who multiplied “with the fecundity of their own rattle snakes.”

Wilkes was an instigator for freedom of speech as well as a reprobate, pornographer, and a liar when it suited him. He sided with the colonies, saying, “Men are not converted by the force of the bayonet at the breast.” He founded The North Briton, a radical newspaper opposing the pro-government publication, The Briton. Wilkes criticized George III’s peace treaty with France at the end of the Seven Years’ War. Considered one of London’s ugliest but most charismatic men, Wilkes made his radical views felt throughout England and the colonies. It wasn’t long before British citizens were carrying signs that read, “Wilkes and Liberty.” America, too, was soon espousing Wilkes’s notions of freedom of the press and liberty for all.

Moore has an ear for apt quotes and uses them liberally throughout his text. But ultimately, his special talent lies in his ability to convert sometimes dry facts into a compelling narrative. He writes his story as if it were a novel, with cliffhangers and telling details to showcase his protagonists. And as Moore describes them in this engaging if somewhat overly long history, they become unique personalities that readers can care about.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Diane Scharper is a poet and critic. She teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.