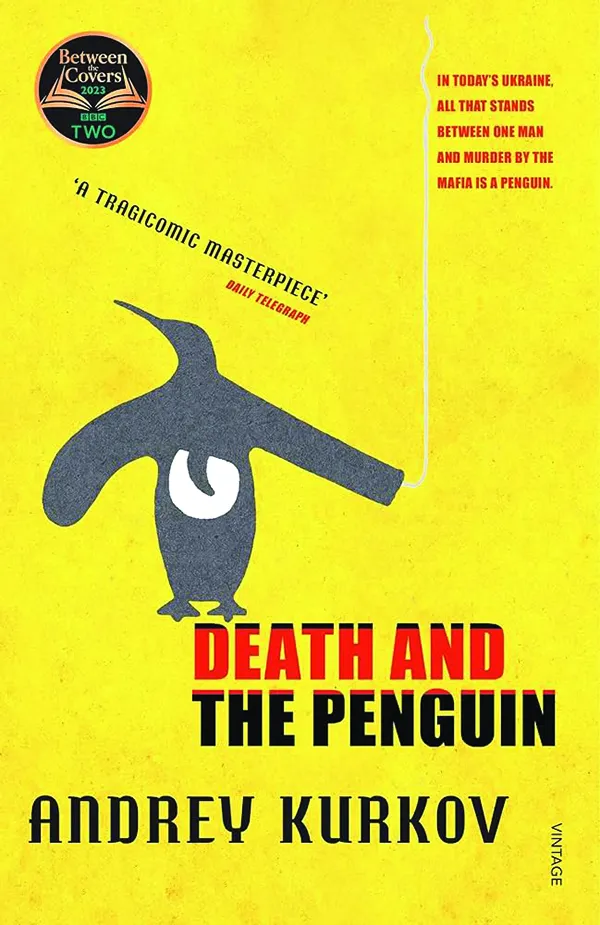

Originally published in 1996, Andrey Kurkov’s novel Death and the Penguin, which follows a humble obituarist and his pet penguin in post-communist Ukraine, finds tenderness and comedy in bleak circumstances. Lies are endemic, and murder is commonplace, but there is enough warmth and humour for one to feel the power of evil in the knowledge of the goodness against which it works.

Kurkov has an obvious interest in the tension between human (and animal) vulnerability and human (and animal) strength. God knows we are vulnerable. The Silver Bone — the first novel in the Kyiv Mysteries series, published in 2020 — begins with the idle butchering of Samson Kolechko’s distinguished father. Having already lost his mother and sister — as well as his ear, in the same attack that robbed him of his father — Samson is left to face a poor and violent Kyiv alone.

It is 1919. The Bolsheviks control the city, but will they tomorrow? Its occupants have seen too much chaos and cruelty to do anything but survive, with communists, Russian nationalists, and Ukrainian nationalists fighting over the country. Unwilling to be a mere victim, submissive in his powerlessness, Samson joins the Bolshevik police and their attempt to bring order to the city. Samson is no kind of ideologue. He just wants people to stop stealing his stuff.

Again, Kurkov finds tenderness amid the terror. Samson aches as he recalls the dacha his family visited in more innocent times. “How can so seemingly recent a past feel so distant, as if one had read it in a book and not lived it?” Like Japan’s Haruki Murakami, Kurkov has a keen sense of the profundity of food and drink. “Each of them downed a shot glass of medicinal alcohol.”

There is humour, too, though it is often coal-black. Samson’s father’s coffin has a strange board fixed to it. “Where we were short of good wood we used planks from an old fence,” shrugs a clerk, “But perhaps it was a fence your father knew well from his walks?”

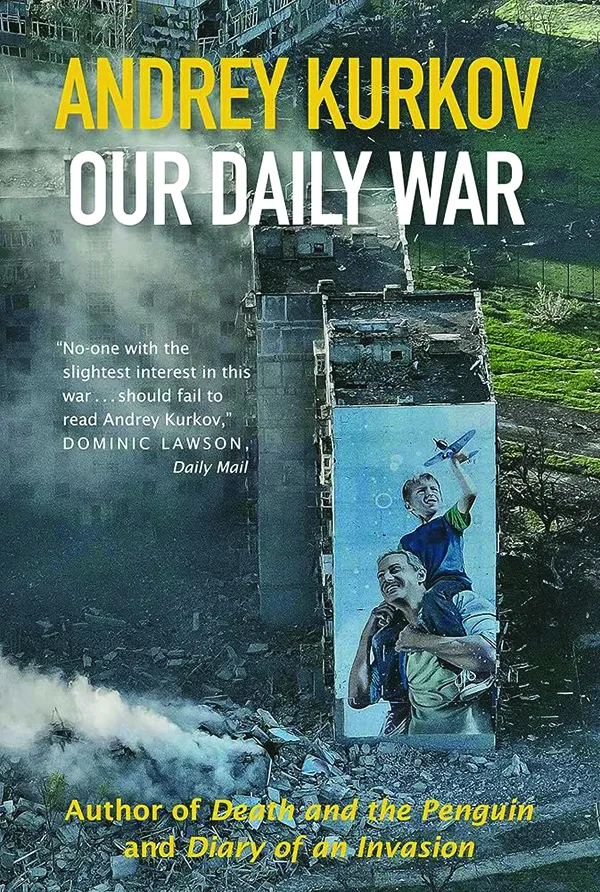

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Kurkov has found himself turning to nonfiction. Reading his 2024 book, Our Daily War, one finds painful parallels with The Silver Bone. “In our apartment in the centre of Kyiv,” writes Kurkov in his diaristic account of Ukraine’s resistance to Russian aggression, “the temperature never rises above 18°C in winter. Quite often it drops to thirteen. We are already accustomed to the cold.” Samson faced the same chill in his war-torn winter. Once again, Ukrainians are enduring what Kurkov calls the sickness of war.

There is little sense of a collective struggle in The Silver Bone. Ukrainians are too desperate and cynical for that. Samson is investigating a micro-mystery in an ocean of individual tragedies and lies. In Our Daily War, on the other hand, Kurkov is a patriotic, political animal. A major theme is the need to promote Ukrainian culture. “The spirit of the nation is kept alive by the souls of dead writers and poets,” Kurkov observes, elsewhere asking readers: “Find books by Ukrainian writers, take the time to learn a little more about Ukraine than you know now, so that it becomes closer to you.”

What Ukrainian culture? What Ukraine? Kurkov is under no illusions about the thorny questions of identity that bedevil his homeland. He is fascinated by the blurred lines between Ukrainian and Russian culture and the Ukrainian and Russian people. But a blurred line is still a line. Kurkov has Russian ethnic roots, and Russian is his native tongue, but he is a proud Ukrainian. Ukraine exists, he writes, not in spite of cultural and ethnic complexities but in part because of them. “I live in a beautiful country with a complex character and complex history,” he reflects, “Where each citizen has his or her own image of the Ukrainian state in their head and everyone considers their image to be the correct one. In other words, we are a society of individualists.”

This only goes so far, of course. A society of individualists needs enough of a sense of collective identity to, say, successfully raise an army that can resist an invasion. But resist an invasion the Ukrainians have — with a sense of individual daring and ingenuity and a collective sense of sacrifice.

Kurkov is an artist, not a propagandist. He is not blind to the moral dilemmas that face Ukraine, though he often approaches them with a light touch. His account of attempts to demonize Russian culture in toto ends with a barbed observation about how petty they must seem to Ukrainian soldiers who are actually fighting Russians. He also reprimands intolerance to debate or satire within Ukraine by noting its similarity to that which might be found in Moscow or Grozny. One painful, neutrally recorded passage describes Ukrainians who have fled the country to avoid mobilization. The patriot and humanist either avoids comment or cannot think of what to say.

Still, as in his novels, Kurkov finds the light of humour in the darkness of suffering. Commenting on Russian attempts to frame military withdrawals in positive terms, he wrote, “Ukrainians have suggested a new military term that the Russians might use to better describe these tactics: ‘advancing negatively’ on the Kharkiv front.” But laughter only goes so far. It ends at the barrel of a gun. Kurkov is blunt about how war, framed by the Russians in ludicrous emancipatory terms, has been snuffing out human potential. Volodymyr Vakulenko was a popular children’s author who was taken from his home and executed in the Kharkiv region. He died like many of his readers.

HOW TYRANNICAL GOVERNMENTS’ MONEY MADE AMERICAN CAMPUSES AUTHORITARIAN

War has obstructed Kurkov’s fiction, but new English translations still emerge. The Stolen Heart, first published in Russian in 2021, is the second novel in the Kyiv Mysteries series. Samson is still a detective, struggling to find order amid social and political chaos. But at what price? And after his war-imposed hiatus from fiction, Kurkov finished the third novel in the Kyiv Mysteries series last year. No one can demand that an author feel inspired — and the fact that there was poetry after Auschwitz need not mean that one man must write novels after Bucha — but I am glad. As Kurkov himself expresses so eloquently in Our Daily War, Ukraine cannot simply hang on.

Still, Kurkov is optimistic about Ukraine’s chances of winning the war, by which he means reclaiming all the territory it has lost since 2014. Frankly, I am not. Inequalities of men, materiel, and money seem too great to overcome — and words and dreams can be no substitute for practical necessities. Yet in a sense, the Kremlin has already lost. Ukrainian outrage and fellow-feeling, animating all of the creative and industrious potential that Ukraine already had, will ensure that Putin’s desire to Russianize the country will remain more implausible than the Armed Forces of Ukraine retaking Crimea. The sane and cultured voice of Andrey Kurkov provides substantial evidence of this.

Ben Sixsmith is the online editor at The Critic.