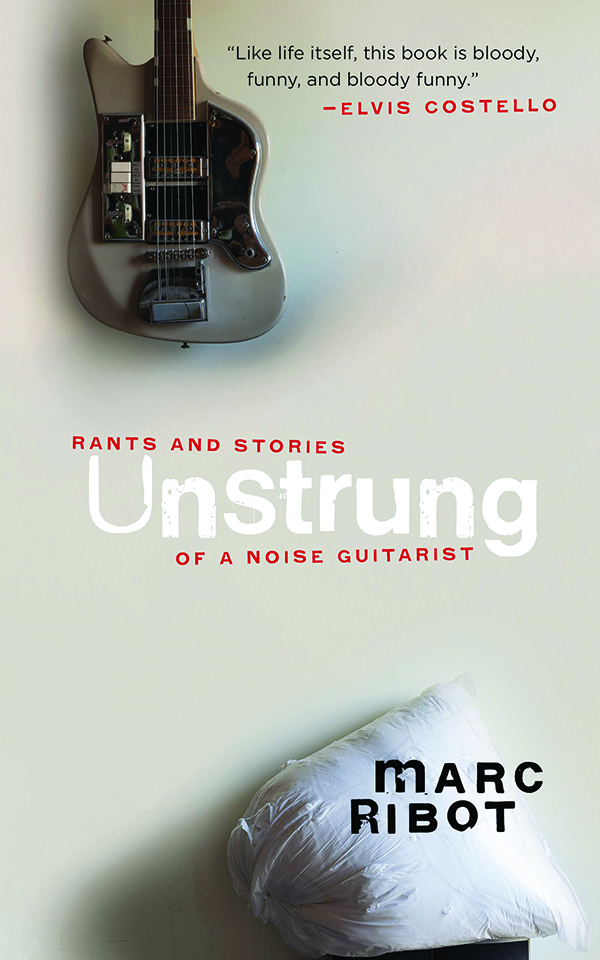

Marc Ribot’s new book, Unstrung: Rants and Stories of a Noise Guitarist, begins in a surprisingly earnest fashion for a musician who is considered the epitome of cool: “Hi. My name is Marc. I’m a guitarist who points extremely loud amplifiers directly at his head. Very often. Sometimes as often as two hundred nights a year for the past forty-five years. Audiologists say this could make one’s ears howl, create an uncomfortable sensation of density in one’s head, and eventually make it impossible to hear human conversation. Yet I persist … Why?”

I’m not sure Ribot could answer that question even if he wanted to, but for a small subset of serious music geeks, whatever response the legendary guitarist gives is going to be of interest. Ribot first rose to acclaim in the 1980s, when he helped create the carnival-inside-a-trashcan soundscapes of seminal Tom Waits albums such as Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years and played with the funky free-jazz hipster favorites the Lounge Lizards. If you’ve never heard Ribot, it’s difficult to get a handle on his unorthodox musicianship. His off-kilter guitar lines don’t melodically cascade so much as fall down the stairs, and yet Ribot’s every choice seems perfectly considered simultaneously to challenge the listener and serve the song. (To get a concrete idea of what he’s capable of, cue up the Lounge Lizards’ “Big Heart” from their Live From Tokyo album and listen for the exemplary Ribot guitar solo.)

For the last 40 years, he’s been a sought-after session guitarist by the likes of Paul McCartney, Elvis Costello, and Beck. When he’s not working for the biggest rock stars around, Ribot’s managed to keep a toe in the underground, collaborating with everyone from trip-hop pioneer Tricky, cutting-edge jazz musician John Zorn, Japanese indie rockers Cibo Matto, and critically acclaimed songwriter Sam Phillips. He even did an album with Allen Ginsberg.

With a career like that, you can expect that Ribot knows how to express himself, and not just musically. The first two essays in the book offer some rather stunning insights into the nature of the electric guitar, its mechanical development, and how the volume and noise it introduced culturally affected music. Not surprisingly for anyone familiar with Ribot’s playing, he elaborates on how he views playing guitar as a literal and metaphorical struggle:

He also speaks profoundly and generously about learning from other musicians. In a piece titled “World Music: Time and Money,” Ribot details his experiences working with musicians from around the globe and in the process recounts his difficulty adapting to different rhythmic sensibilities. He had to learn the hard way that for some African musicians, time is round rather than linear — songs do not have discrete bars and meters with a beginning and an end. In attempting to play Peruvian music, he realized after the fact he’d been attempting to play along in 3/4 time but his Western music sensibilities prevented him from realizing the Peruvians were playing four bars of three. The essay works well on two levels: It offers a fascinating examination of musical theory that is both an implicit and explicit plea for cultural understanding.

Along these lines, Ribot also offers up a heartfelt and elegiac tribute to his first guitar instructor, Frantz Casseus, a famed Haitian composer who combined elements of classical guitar and Haitian folk music. It’s ultimately a tragic and familiar tale: Even though Casseus’s songs were recorded by big-name artists such as Harry Belafonte, Casseus suffered a series of debilitating injuries and died in penury after years spent trying to recover thousands of dollars in royalties owed to him. Shortly before he died, he finally received a check for $16,000, and Ribot recounts with a pronounced bitterness that Casseus said, “If I had known, I would have composed more. I felt my work to be without value.” This tragic tale spills over into “The Attack on Artists’ Rights … and Me,” a righteously angry essay about the efforts to screw musicians out of the money they are owed that evinces a fairly good understanding of our broken copyright laws and the threat to freedoms posed by Google and other Big Tech companies.

But even the best musicians, to say nothing of one as daring as Ribot, hit a few clams. And the more Ribot strays from the topic of music, the more his writing resembles that of a rhythmically challenged musician who can’t seem to land on the one.

The book’s foray into politics is a reprint of the liner notes to “Songs of Resistance,” a Trump-era album of protest music that Ribot organized. Despite recounting some interesting musical history, it’s shot through with Ribot’s sadly predictable boomer politics. It’s an understatement to say the thoughtful and nuanced approach to cultural differences elsewhere in the book does not extend to Americans living outside Manhattan.

Another piece in the book, “Everybody’s A Winner,” is a short story or, God forbid, an autobiographical literary sketch about a musician having an affair with a bisexual former model amid the backdrop of art galleries in Chelsea. Suffice to say, the whole indulgent mess provides an unflattering contrast to the flashes of hectoring morality elsewhere and can be summed up by perhaps the single most groan-inducing line I’ve encountered in a while: “Parting had its own bittersweet semiotics.”

Fortunately, there’s much more worthwhile here, including essays on Ribot’s friend and seminal punk guitarist Robert Quine, the poetry of enigmatic jazz bassist Henry Grimes, and an amusing detour into the ne’er do wells that inhabited the New Jersey lounge act scene of the 1970s. The few lackluster pieces in the book can be easily overlooked, and at its best, Ribot’s writing resembles his music: It’s challenging, unique, and very humane.

Mark Hemingway is a writer in Alexandria, Virginia.