“It’s too country for rock and too rock for country.” That’s what record company executives would tell Lucinda Williams to explain why they wouldn’t be signing her to produce an album. Thus one of America’s most revered songwriters spent nearly two decades struggling to find a place in a music business too rigidly genre-bound to take a chance on her boundary-breaking style.

Fifteen studio albums later, Williams’s status as an icon of American music is secure. In June, she released Stories from a Rock n Roll Heart, joined by the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Margo Price, and Angel Olsen on backup. This summer, she’ll tour alongside youthful indie folk band Big Thief, proving her power to appeal across generations.

THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF WHEN WAYLON JENNINGS AND BILLY JOE SHAVER CREATED OUTLAW COUNTRY

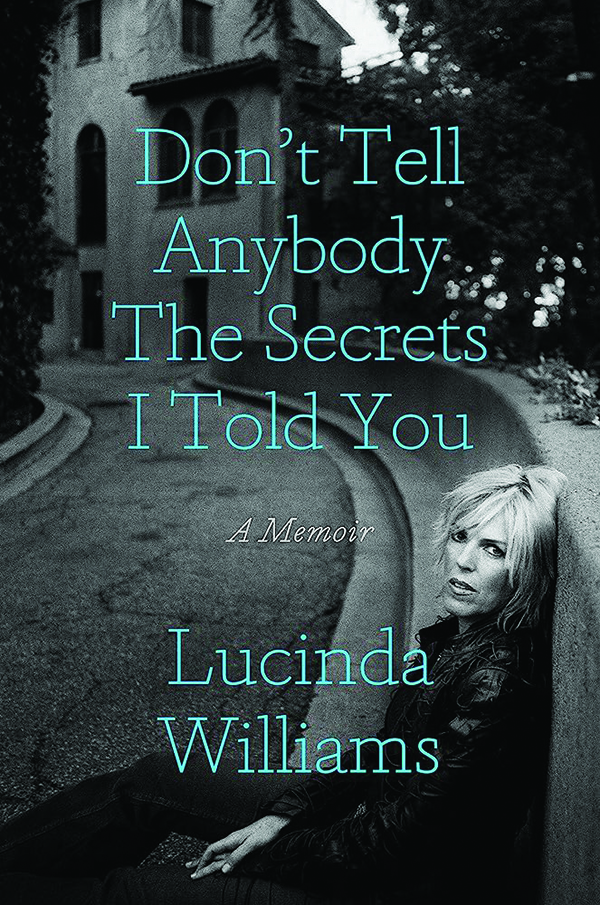

Williams has always told true stories through song. Now, she finally tells her own through prose in her new memoir, Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You. As is evident from her music, this is not an entirely happy story. Williams’s songs are rife with funerals, deaths, and suicides. Others are portraits of men she described in the past as “beautiful losers,” poetic types done in by their tragic flaws and excesses. She isn’t one to veil the meanings of her lyrics behind layers of mystery, so the revelations in her memoir are less about decoding obscure metaphors than detailing the specific people and circumstances that inspired her songwriting.

When she mentions a poet from Subiaco, Arkansas, for example, fans will pick up the grim foreshadowing. Subiaco Cemetery is the final resting place for a friend who shot himself with a .44, described in her bluntly documentary song about his death, “Pineola.” The gist of that story is clear enough from the verses, though it only hints at the life of the deceased. Her memoir adds vivid detail, introducing the wild Southern poet Frank Stanford and recounting how two of his many lovers confronted him for philandering and demanded he stay loyal to one of them. He took his life the next day.

She is equally candid about her own tumultuous childhood. She was rarely in one place for long, moving nearly a dozen times by the age of 20. Her mother suffered from mental illness and alcoholism. Her parents split during her adolescence, and her father took up with one of his undergraduate students, formerly the family’s babysitter. Williams reflects on this hardship with generosity of spirit, accepting this familial dysfunction as ultimately less important than what she gleaned from the experience. “What matters is that I inherited my musical talent from my mother and my writing ability from my father,” she writes.

It’s to the latter, the poet Miller Williams, that her book is dedicated. For all her childhood adversities, her father also exposed her to a rich Southern literary scene. At 8 years old, the two of them paid a visit to Flannery O’Connor. Later, in Fayetteville, Arkansas, Miller Williams hosted wild parties for the literati. Charles Bukowski was there, she says, hooking up with another writer in the downstairs guest bedroom. If all the stories are to be believed, that one bedroom hosted Bukowski, Lucinda Williams, and Jimmy Carter at various times, though presumably not for the same purpose.

Miller Williams’s poetry fellowships also expanded his daughter’s experience beyond the American South, first as a young girl in Santiago and later to Mexico, where she played her first live shows singing American folk songs on a goodwill tour sponsored by the American Embassy. He was supportive when she dropped out of college to stick with her first regular gig as a musician, performing for tips in a joint on Bourbon Street. She recognizes this as a turning point in her life, one illustration of how her youth provided both the grim Southern Gothic inspiration for much of her songwriting as well as the encouragement and opportunity to develop her voice.

Another turning point came in 1988 with the release of her eponymous album on the British label Rough Trade. Stuck playing the same shows in Los Angeles, nursing rejection after rejection from American music executives, the offer to record came out of nowhere. “I’ve always enjoyed that it took a British punk label to give me a chance to make a commercial record,” she writes, an irony for an artist now viewed as an exemplar of modern Americana.

This album was also where Lucinda Williams began exploring one of the other great themes of her music. She writes about lust and desire better than just about anyone. “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad” finds her driving through the night to meet a paramour at his hotel. Then there’s the Grammy-winning “Passionate Kisses.” Both seem innocently quaint compared to later work depicting moaning self-pleasure while recollecting a past lover or likening erotic desire to the gripping need for a heroin fix.

We get the backstories to many of these songs in her memoir. “A poet on a motorcycle” is how she describes the type of man she’s always been attracted to: “There’s a part of me that wants to stay up all night and talk about philosophy and art, and there’s another part of me that wants to be dragged into the bedroom.” A man who can do both is irresistible, for better or worse. Listen to how she channels anger, yearning, and hurt in one of her rawest verses, “Did you love me forever / For those three days,” from her 2003 album, World Without Tears. We learn in the memoir that the affair that inspired this number was disappointingly unconsummated; Lucinda Williams is an artist who knows intellectual and erotic connection can be most powerful at their most fleeting.

Now 70, she is at last a bit more settled, living in Nashville, Tennessee, in what seems by all accounts an unequivocally healthy marriage. She omits mention of a recent stroke that has lately robbed her ability to play guitar, but she still tours and still produces amazing work. The story that emerges is one of a life lived fully and hard, now reaching a degree of reflective contentment and well-earned success.

“Shouldn’t I have all of this?” she sang on that breakout album 35 years ago. One of music’s most beautiful souls, no one deserves it more.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Jacob Grier is the author of several books, including The Rediscovery of Tobacco, Cocktails on Tap, and Raising the Bar.