I don’t remember exactly when Korea eclipsed Japan as the go-to country for beauty, which itself had been in fierce competition with France, but it must have been sometime in the early 2010s, maybe 2010 or 2011. Conversations about beauty were dominated by Korean cosmetics, Korean skincare, and Korean plastic surgery. Digital communities, podcasts, and YouTube channels started mushrooming everywhere. South Korea, it seemed, just did it better. They offered affordable snail mucin that made our skin baby soft, foam cleansers that smelled like freshly picked strawberries, and sheet masks that promised everything from glassy, poreless skin to no more dark circles.

By the late 2010s, a little under a decade after K-Beauty emerged as a phenomenon among beauty insiders, the rest of the country caught up. By now, South Korea has long been the standard-bearer of skincare and cosmetics. Forget Sephora taking a cue from the Face Shop, one of Korea’s most popular cosmetic brands; even Walgreens now boasts a K-Beauty section. At the very least, you’ll find a wide selection of sheet masks, easily the breakout star of the K-Beauty phenomenon.

YOU CAN’T NIP AND TUCK YOUR EGO

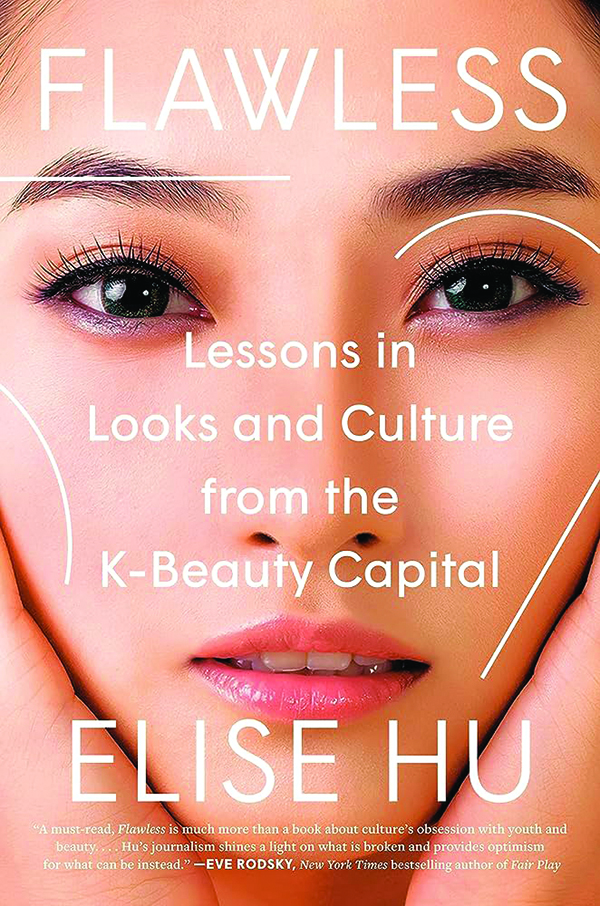

What never seemed to emerge in the United States, despite our love affair with Korean cosmetics, is the subject of Elise Hu’s new book, Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital: an unforgiving beauty standard.

In the introduction to Flawless, Hu takes a tone that feels a little precious. Words like “attractive” and “beauty” are placed in scare quotes. It smacks of the type of carefulness that’s become customary in social justice tracts, the ever-present parenthetical reminding us that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. It quickly becomes clear why she chose this language, though. It’s not that Hu is being overly sensitive. It’s that the beauty culture of South Korea is prescriptive in a way that would be completely alien to American readers.

Women here often speak of the pressure to conform to certain norms. But everywhere in Korea, the same perfect face is broadcast in a way that seems completely untenable in the United States. Korean beauty is strictly defined and strictly enforced for both men and women. “The visage is inescapable,” Hu writes, “milky white, smooth, glowing, with a narrow nose, anime-sized eyes, and a small, delicate jawline that meets at a V.”

Looks-based discrimination isn’t felt “between the lines.” It’s not something that subtly shifts from environment to environment, industry to industry, in the same way beauty standards vacillate wildly between suburban Oklahoma and Orange County, California. In Korea, lookism, which is forbidden by a 1995 discrimination law, is a cultural and economic norm. Job descriptions mention preferences for “pretty eyes” and “high noses.” Job applications require headshots. Hu writes. “Looking pretty … isn’t just important, it’s the price of entry into the labor market.”

To buck trends, to deliberately “uglify” oneself, even by merely foregoing makeup, has real social and economic costs. When Hu writes about the #EscapetheCorset movement, a group of nearly 300,000 women who decided to protest beauty standards, it doesn’t have the same self-satisfied tone an American equivalent might. The truth is, in the United States, it may be in bad taste to go to Starbucks in your pajama pants, but nothing will happen if you do. If you roll into your office with a messy bun and no makeup, you might be teased, but you won’t get fired. Being ugly may be less glamorous than being beautiful, but in reality, the costs are not as deeply felt.

But in Korea, looks are everything, and in a way that we may never truly understand.

In the U.S., beauty lingers somewhere between a hobby and a luxury. Beauty knowledge is transmitted through TikTok and YouTube tutorials and Rolodexes of instructive subreddits — the kinds of things that are, frankly, easy enough to avoid. And while it can feel like a necessity, we know deep down that we can live without it — just like we can live without a doorman apartment or Ubers or a membership to Barry’s Bootcamp as opposed to Planet Fitness.

While Americans long for younger-looking skin, smaller noses, and slimmer jawlines, we lack a unified beauty standard. We have deconstructed ourselves — and as a result, beauty — into individual parts, like a computer that’s being upgraded, bit by bit. We are, in some sense, beauty nihilists. Or perhaps we’re beauty accelerationists. Our quest to look “better” is less about fitting some sort of hegemonic ideal and more about unlimited consumption. The American beauty industry has no end goal. Change your skin, change your hair, change your gender; it doesn’t matter. There’s something about the fact that we can do it at all that appeals to us.

Hu writes that South Korea is the future, almost as a warning. But this shift seems unlikely. Yes, it’s likely the future insofar as trends and products. Korea has historically been a decade or more ahead of the curve with plastic surgeries and cosmetics. Otherwise, it seems improbable that Korea’s beauty culture will ever fully take root in the United States. If Americans are beauty nihilists, then Koreans are beauty fascists.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Katherine Dee is a writer and co-host of the podcast After the Orgy. Find more of her work at defaultfriend.substack.com or on Twitter @default_friend.