“History doesn’t repeat itself,” Mark Twain reputedly said, “but it often rhymes.” Twain’s actual words, found in his 1873 book The Gilded Age, were less pithy: “History never repeats itself, but the kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends.” The echo of that statement first appeared in print around 1970, a fractured quote for a fractured age. Not the same thing, but close enough.

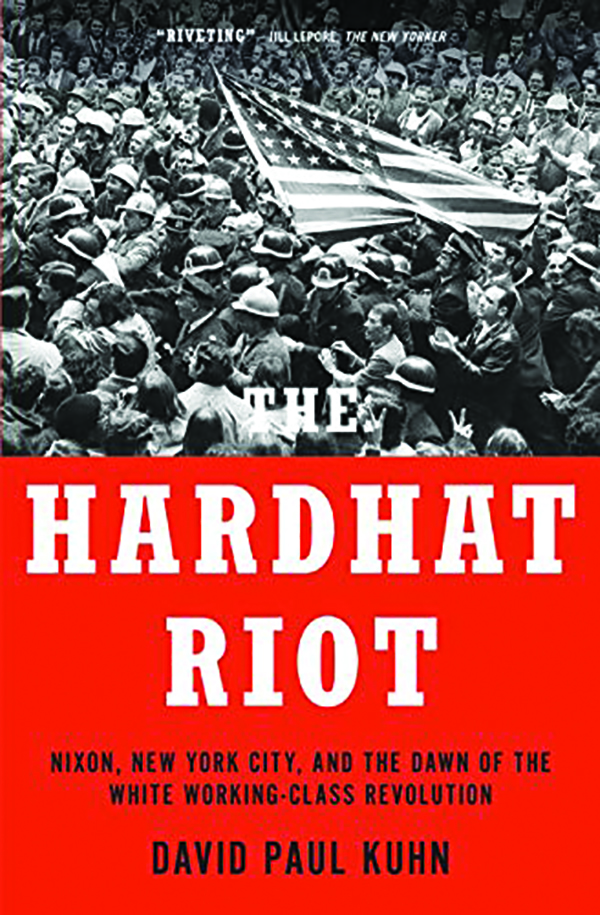

Reading David Paul Kuhn’s The Hardhat Riot here in 2020, one cannot help but see the same “kaleidoscopic combinations” of the 1970 events he describes now, 50 years later. The clash Kuhn describes is between two core Democratic constituencies, college students and union construction workers, that found themselves having little in common. Radicals to one side, working people to the other. It sounds a lot like the conflicts of today. It isn’t, exactly. But it is close enough to give us a frightening preview of what comes next.

Kuhn takes the reader back to a time when the United States was riven by political and social conflict. The civil rights movement had already achieved some major successes, but the fight for racial equality still drove people to protest. The war in Vietnam continued to be unpopular, and by 1970, Richard Nixon’s expansion of the conflict into Cambodia had brought anti-war sentiment to a boil. The shooting at Kent State on May 4 of that year ratcheted up tensions even further.

But there were other social cleavages that many found hard to understand. The people demanding the biggest changes were those — college students — who had benefited the most from the system. At an anti-war rally outside the New York Stock Exchange in early May, blue-collar policemen and construction workers were baffled by the contempt the college student demonstrators had for the country. “Many saw spoiled brats protesting,” Kuhn explains, “kids dismissing advantages they never had while scorning them for doing their job.”

By itself, anti-war sentiment was not a problem for many of the workers in the police and building trades. Many of them doubted the wisdom of fighting in Vietnam, where their friends and family were disproportionately likely to serve. But whatever their doubts, they and their sons served, trusting in their elected leaders to do what was right.

The Watergate scandal a few years later began to erode that deference to authority. But for the hippies, such deference was already gone, along with respect for the nation and its symbols. The daily insults to the U.S. and its flag grated on the men in hard hats and police hats. Meanwhile, New York’s mayor, John Lindsay, courted elite opinion by praising the protesters, even calling them “heroic.”

The hardhats organized a counterprotest on May 8, 1970. Workers streamed in from nearby job sites to praise the country, the flag, and the sacrifice of the troops in Vietnam. Hippie tactics had evolved in the past few years to include actions intended to provoke. (We see the same schemes today: Radicals take to the streets and do anything they can to inspire the powers that be to strike back.) By 1970, police were mostly wise to the ploy and declined to respond to the foul-mouthed flower children. That restraint was never cultivated among those who did not have to face such insults daily. The construction workers took the hippies’ words to heart and responded with force. The police were capable of corralling peaceniks, but when hundreds of angry men hardened by years of physical labor pushed back, the blue line broke.

After the fact, many accused the police of letting the workers through, and Kuhn chronicles the ample evidence that the police sympathized with the hardhats. The two professions drew from the same classes and neighborhoods and had similar outlooks. The police were not allowed to swing at their upper-middle-class antagonists, but they likely did not mind someone else doing it for them.

The protest turned into a riot, and the casualties were largely one-sided. After clashing with the hippies, the workers streamed north to City Hall, where Lindsay had ordered that the American flag be hung at half-staff after Kent State. Again, the police were outnumbered and disinclined to tangle with a mob capable of fighting back. After some scuffles, the deputy mayor, Dick Aurelio, ordered the flag raised back up before the workers took over the building.

That was enough for the day. After some patriotic singing, the men disbursed — most of them back to work. Radicals who had for years dreamed of a workers’ revolution got a glimpse of one, if only for a few hours. They did not like what they saw. The workers did not want socialism. When they rioted, it was for flag and country.

“Washington is not Corinth,” Twain wrote after his line about the kaleidoscopes, and here again, he is correct. New York is not Seattle or Portland, and 1970 is not 2020. But the trends that led solid citizens to riot are present now just as they were then. Today, we have no military draft, and our overseas wars are winding down. The past 50 years have seen tremendous progress on civil rights — even if some real grievances remain. Yet the enraged protesters in the streets these days are every bit as radical as the hippies — often more so.

Protests that began with a complaint most could understand — outrage at the killing of George Floyd — quickly devolved into an orgy of statue-toppling, America-hating chaos, much of it in conscious imitation of the late 1960s. Like Lindsay, most local mayors came to praise the radicals. But in 2020, corporate America and the legacy media were on their side too. Our leading institutions praised the increasingly unhinged protests as heroic. But can it be heroic to do exactly what the corporate and media establishment wants? The counterculture of 1970 is the establishment culture. The rejection of classical American virtues is now official dogma.

Still, their protests rhyme with history. So do the slogans of their opponents. Nixon gave speeches about the blue-collar workers, calling them a “Silent Majority.” Trump, for his part, sends an all-caps tweet: “SILENT MAJORITY!” They are, it is true, increasingly silent. But are they still a majority? And what will they do now, should they choose to break their silence?

The Hardhat Riot shows what can happen when the establishment and the counterculture align to denigrate the values and symbols of Middle America. It is not a pretty sight. One might cheer the workers’ counterprotest in 1970, but we should not wish for the violence that followed it. Americans will defend America. The Hardhat Riot shows us the perils of leaving that task to a mob.

Kyle Sammin is a lawyer and writer from Pennsylvania and the co-host of the Conservative Minds podcast. Follow him on Twitter at @KyleSammin.