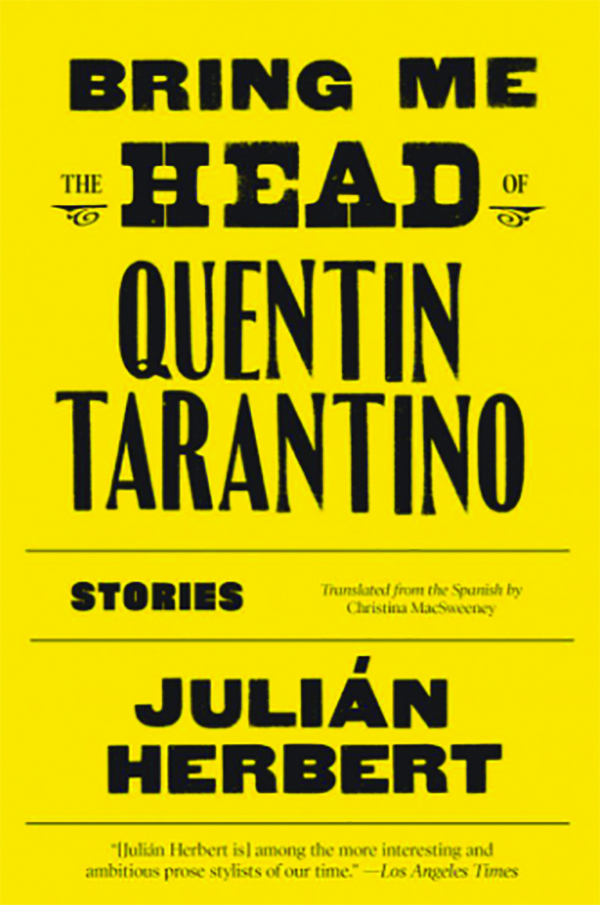

The 10 stories collected in Julian Herbert’s Bring Me the Head of Quentin Tarantino seem, at first, to have been engineered using the very artistic DNA of the collection’s namesake. Like the films of the American director, the stories of the Mexican author are a concoction of the urbane and the savage. Sophisticated protagonists convene with subterranean society and return to report surreal, nightmarish encounters in the vigorous and cynical language of hardened adventurers. They are formally very clever, upending genre tropes, telling stories within stories, fluidly switching between points of view, and otherwise testing the limits of narrative reliability. One story even includes sheet music and pictures of the inside of the protagonist’s mouth.

And much like Tarantino’s films, Herbert’s stories may prove too showy and divisive for some people — people like me who don’t much care for Tarantino. But this knee-jerk rejection may ill-serve Herbert’s fiction, with its literary sophistication and unique satirical bite lurking beneath the flash.

The hyperkinetic tenor of this collection is set down in the first story, which begins with Max, a failed filmmaker-turned-office drone who is caught in the middle of a corporate scandal that includes fraud and arms smuggling into Nicaragua. It then switches to the direct point of view of the narrator: a “personal memories coach” paid to make colorful embellishments to Max’s experience. “I could have been one of the many fleeting new voices of Mexican literature,” the narrator claims. “But I refused. … I refused because I am smart: I want to be corrupted by money, not flattery.” But when his clients don’t pay, he hijacks their “memories and anecdotes” with his own literary touches, sometimes “offering them as short stories … to cultural publications and literary supplements.”

“I’m a true Mexican businessman, and that means I’m trained to carry out or condone any low-down action in exchange for money.”

Herbert has a fondness for disillusioned creatives akin to what a cosmetics lab technician might feel for the rabbits he stuffs with experimental chemicals. In “NEETS,” a conceptual artist who specializes in gruesome pornography is tortured by the thought that he is fathering a literal “Exterminating Angel” who can kill anything at will. “Caries” tells of another conceptual artist with “blind faith in his own point of view, his own aesthetic conscience,” who discovers “sheet music in his teeth.” He transcribes the music for an exhibition only to be accused of plagiarizing a preexisting composition.

In “M.L. Estefania,” a crack-addicted ex-tabloid journalist poses as the titular author of Westerns to make ends meet. He ends up on a speaking tour of a hundred schools and colleges. When the narrator expresses doubts about the fraud, his more efficiently corrupt partner dispels them: “It’s not fraud: we’re working in a gray zone created by postmodern education and culture. The death of the author and all that crap you go on about in your talks.” The title story centers on a film critic kidnapped by a drug lord whose resemblance to Tarantino betrays an obsession with his films. It is the longest story, more of a novella really, that doubles as a satire on cartel violence and the pretensions of academic criticism, including long discourses on Harold Bloom, parody, and the nature and craft of writing.

Herbert’s stories exemplify what might be called pulp surrealism. His fiction is equally comfortable depicting the madcap violence of a neo-Western as it is exploring the bizarre inner space of the human subconscious. It is where Death Valley and the uncanny valley meet.

In “There Where We Stood,” two academics in Chile think they’ve spotted Juan Rulfo, the long-dead Mexican master of the short story, eating in a bar. “White Paper” recalls at once the angular prose poetry of Donald Barthelme and the ghost stories of M.R. James, told from the ghost’s point of view. “The Dog’s Head,” centered on a partially eaten croissant left on a seat of a Berlin train, imagines a kind of expressionist Nicholson Baker. The most realized of these experiments, though one I wish was longer, is “Z,” in which a man keeps his appointments with a therapist who, along with the rest of the world, is slowly succumbing to a zombie state:

“Practically the whole army has been infected to some extent. … And although it’s true that they get the best vaccines, it’s also the case that cells of deserters spring up on a daily basis (or at least that’s what CNN says: the national media have disappeared), at the service of the worm catchers. Anything that still functions here relies on corrupting everything else until it becomes an allegorical mural of destruction.”

As with fellow Mexican author Fernanda Melchor’s novel Hurricane Season, published in English earlier this year and reviewed in these pages, Herbert’s stories take a candid, cynical view of Mexican society. Violent crime, political corruption, and the overall cheapness of life are taken as givens. But both authors use inventive, discursive, and nonlinear narrative methods to counteract the brute cynicism of their stories’ content. Their success in doing so suggests that literature clarifies and accentuates the absurdity of common — and not-so-common — cruelty better than prestige television, cable news, or digital media can ever hope to.

The prestige of the short story in the United States rests somewhere between that of the thought experiment and that of the TV pilot pitch. American readers will delight in Herbert’s lapidary style and gallows wit, and they may also appreciate his cleverness for its own sake. But the candor, disillusionment, and moral and social precarity depicted within the novel is something they would have to go back in time to recognize in their land — back to a time before the U.S. was a world power, when it was not quite as well understood as it is today. Back, that is, to the time of Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Herman Melville. The posthumous fame that these writers achieved can sometimes obscure the strangeness at the heart of their work, shaped in no small part by their own social precarity and by the wild physical and human landscape in which they wrote. Whatever differences in style and subject between those authors and this new generation of Mexican writers, their work has the same quality for their respective readers, coming on like storm clouds in the same darkness, drenching them in the same overwhelming torrents.

Chris R. Morgan is a writer from New Jersey. Follow him on Twitter: @CR_Morgan.