The legendary American artist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) painted in a realistic style and refused to bow to the dictates of modern art, saying he didn’t believe that “these novelties” should claim to be “works of art.”

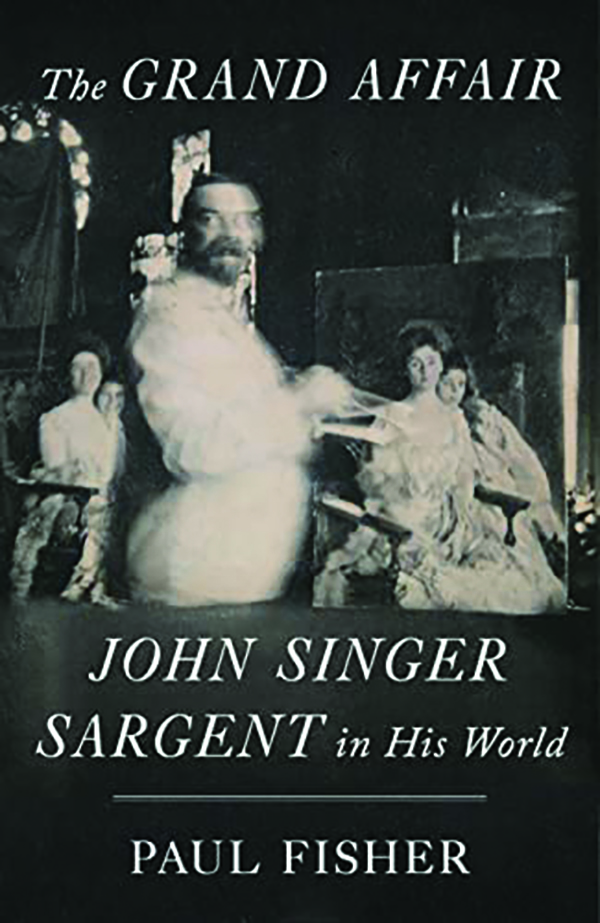

As Paul Fisher’s biography, The Grand Affair, explains it, Sargent disliked controversy but stood up for his beliefs when pressed. He also had an independent streak starting with his unconventional childhood.

Born in Florence to expatriate parents who left Philadelphia for Europe, Sargent came from a close-knit family. They frequented museums, libraries, and notable places where he was exposed to work by renowned artists such as Diego Velazquez and Frans Hals.

His father, FitzWilliam Sargent, a former medical illustrator and eye surgeon, homeschooled him and his two younger sisters, Emily and Violet. John, his father said, had no math ability, but his art was handsomely articulated. By age 14, he rendered entire Alpine landscapes.

FitzWilliam encouraged his children to read the Bible. This would play a large role in Sargent’s magnum opus, The Triumph of Religion, his mural cycle at the elite Boston Public Library, created during the final decades of his life.

His mother, Mary Newbold Singer, was a watercolorist. She sought out places to paint and influenced her children to do likewise. The family lived an itinerant existence visiting warmer countries in the fall and winter and cooler countries in the spring and summer.

When Sargent was 18, the family moved to Paris, and he entered the atelier of the fashionable portrait painter Carolus-Duran, friend of Claude Monet. Later, Sargent attended the exclusive Ecole des Beaux-Arts to study drawing from casts and life.

Sargent established himself in Paris, painting the rich and famous as well as gypsies, dancers, and street children. During the 1884 Paris Salon, his portrait of Virginie Gautreau, shown with bare shoulders and a hanging strap, offended some art aficionados. The picture, later known as “Madame X,” made him persona non grata in the Paris art scene.

Detesting scandal, he moved to London where his 1885-1886 painting, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, triumphed at London’s Royal Academy. He soon became the leading portraitist in Britain and the United States. Sargent painted VIPs such as John D. Rockefeller, Lady Randolph Churchill, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Henry James, a longtime friend. Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt sat for him.

In 1918, Sargent enlisted in World War I as an artist and created an epic painting, Gassed, showing a line of hobbling soldiers blinded by mustard gas. The picture was partly inspired by the death of his niece and model, Rose Marie Ormond, who ministered to the World War I wounded and was killed by the Germans during a Good Friday Tenebrae service. Devastated by the loss, Sargent memorialized Ormond’s features in the Pieta image of the “Church” in his Boston murals.

Although he excelled at portraits and landscapes, Sargent believed The Triumph of Religion” his masterwork. Fisher, unfortunately, devotes little attention to Sargent’s religious installation, calling this aesthetic tour de force, “stodgy library decorations.”

Considered an “American Sistine Chapel,” the dramatic installation includes gilded serpents, zodiacs, angels, and the Ten Commandments as it traces the evolution of mankind’s belief in the supernatural from the time of the pagans to the Old Testament and the New Testament. Sargent covers the ceiling and walls with his mural cycle and includes Moloch, Astarte, pharaohs, Jeremiah, Micah, and Jesus. Some Jewish people thought Sargent misrepresented their religion, but after five years, the controversy ended.

Sargent sailed back and forth from England to the U.S. for nearly 30 years as he composed this history. Princeton University’s engaging and well-researched book, Painting Religion in Public by Sally Promey (1999) conveys the inside story of the notable project that was left unfinished with Sargent’s death.

Fisher, a professor of American studies at Wellesley, tries to fathom Sargent’s genius, but he has an uphill climb, since Sargent kept silent regarding personal matters. Although Sargent frequently corresponded with friends and family, he left no documents revealing any matters of the heart with either men or women, so there are gaps in Sargent’s life story. No one knows why Sargent never married. Did he not find the right one? Was he, in Fisher’s term, “queer”? Or was he too busy painting and providing for his mother and sisters after his father died?

Fisher fills in the holes with innuendo, for example, using “My soul longs for…,” a part of a quote, and implying it refers to Sargent’s longing for his Boston model, Thomas McKeller. The complete quotation, however, refers to Sargent’s desire to be in Boston, working on his mural in his studio in the “Pope Building.” It’s a push and misleading to suggest a romantic attachment.

Even Fisher’s title, The Grand Affair, is ambiguously suggesting Sargent experienced a passionate love affair. But read carefully, and you’ll see Fisher is referring to Sargent’s “love affair with the visual world.” While innuendo makes for a more titillating read, it creates a less credible biography.

Fisher insinuates Sargent had homosexual or homoerotic feelings but argues in a footnote, “This book, however, does not make the claim that Sargent was ‘gay’ in the present understanding of the word.” Yet he notes Sargent’s friendships with several men and sketches and paintings of nude men found after Sargent’s death. Many of these were drafts done for his murals that were never completed. Even so, it’s doubtful that anyone can see into an artist’s sexual secrets by looking at their work. This is doubly true with an artist as complex and reserved as Sargent.

Sargent’s supposed homoerotic longings can, according to Fisher, be intuited. Fisher discusses the red color of a bathrobe, for example, and speculates about a possible affair between the artist and his subject, Dr. Pozzi, a gynecologist married with three children.

No matter Sargent’s sexual orientation, he portrayed his subjects in realistic detail, sometimes blending them with impressionistic techniques. During the era of postimpressionism, Fauvism, expressionism, and cubism, he kept his own aesthetic vision and won “whole rooms full of accolades … [including] five honorary degrees, sixteen exhibition prizes. … a Legion d’Honneur from France, a membership in the Royal Academy.”

But modernist art critics derided Sargent’s work. Roger Fry, Bloomsbury member, smeared Sargent, as Fisher compellingly explains, because Fry falsely implicated Sargent as a supporter of postimpressionist art, and Sargent vehemently claimed his “sympathies were in the exactly opposite direction.” Afterward, Fry viciously panned Sargent’s work.

Nevertheless, Sargent’s reputation has endured. Sargent’s Boston murals were restored in 1953 and again in 2003 and 2004. Revealing his bold colors and the nuances of his lines, the restorations garnered further admiration for his style. Nearly 100 years after Sargent’s death, his fame remains secure in the pantheon of American artists.

One hundred and forty of Sargent’s Spanish-themed oils, watercolors, drawings, and photographs, including sketches of saints and crucifixes, “Sargent and Spain,” are now on exhibit at the National Gallery of Art in Washington until Jan. 2.

Diane Scharper is a writer and critic. She teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.