When I was stationed in Germany years ago, some of my fellow soldiers would get bored and pick fights with young Russian men in the local clubs. The German locals never seemed to have the heart to duke it out, and the Russians were not only eager and willing to trade blows, they were an even match. On particularly debauched nights, the club floor would suddenly transition from dancing to punching, a roiling frenzy in the loud dark of Schweinfurt’s Rockfabrik club. What stood out the most to me in those moments wasn’t the violence itself — young soldiers abroad get restless, after all — but how similar the Americans and Russians appeared. Both “sides” were tattooed and weighted down by jewelry, with close-cropped hair and tank tops. Sometimes, you couldn’t tell who was who. In those moments, I couldn’t help but feel a resonance between our two cultures, deeply buried, perhaps, and difficult to articulate, but there all the same. I was convinced that the fighting was really a catalyst for some deeper communion.

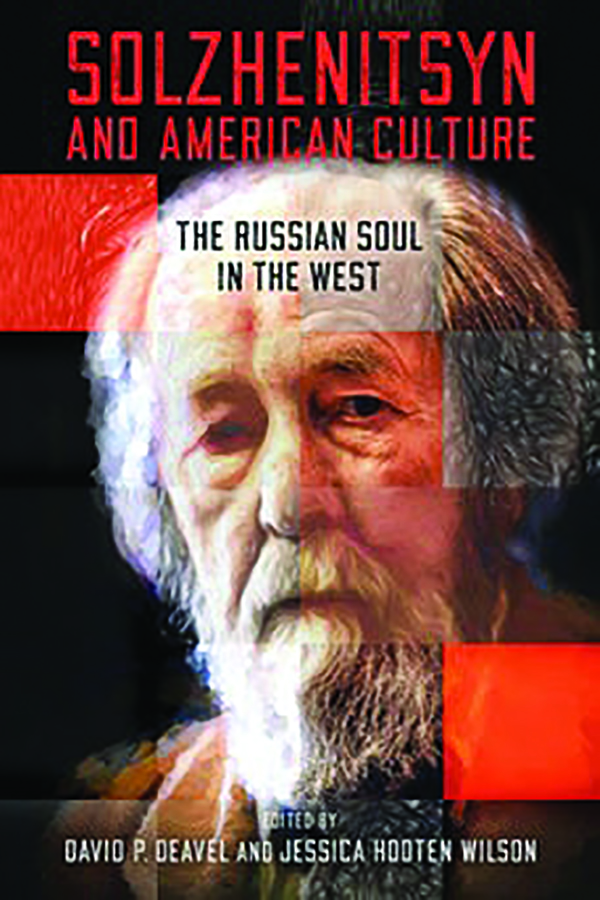

Something of that affinity is captured in the recently published collection of essays Solzhenitsyn and American Culture: The Russian Soul in the West, edited by David Deavel and Jessica Wilson. Many will have heard of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the author of such works as One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and The Gulag Archipelago, but they may regard him as a relic of the Cold War, interesting merely as an example of a dissident victimized by Soviet brutality and censorship. If they know anything about him beyond a general sense that he opposed totalitarianism, they might cite his deep Orthodox Christian sensibility or his sharp criticisms of Western decadence. But this book complicates that understanding both by deepening our appreciation of Solzhenitsyn as an artist and by illuminating the cultural context in which we understand his art.

Nathan Nielson writes in the first essay of the book, “The Universal Russian Soul,” that “a Paradox lies at the center of the Russian character. Its history and politics embrace nationalism, but its culture and spirituality seek universalism. The deeper it burrows into its soul, the further it looks outward. When the defenses go down and Russia opens its heart, it finds its reach cannot fit within its own borders.” Solzhenitsyn and American Culture is the fruit of that paradox, pulling from the Russian notion of sobornost, or a “spiritual community” that emphasizes the suppression of individualism, and drawing on the work of both Americans and Russians in order to explore the universal themes that Solzhenitsyn wrestled with in his fiction and essays: Why is ideology so alluring? Can we ever truly discern the shape of history? What makes a person good?

These questions exist within the tension between the seemingly incompatible values of Russian patriotism and a spiritual, particularly Orthodox, universalism. If these values strike us as uncanny, it’s because we recognize ourselves in them. America, too, believes in its own particular greatness and in its mission to redeem the world. Both countries are large and contain multitudes. In the paradox between our own brutality and our rich spirituality and artistic culture, we contradict ourselves.

The book is roughly organized into five different sections, each focusing on a particular aspect of Solzhenitsyn’s work. Perhaps the most interesting section is titled “Solzhenitsyn and Russian Culture,” which contains two particularly gripping essays from the contemporary Russian fiction writer Eugene Vodolazkin. In “The New Middle Ages,” Vodolazkin writes that “in my view, the coming epoch’s intent attention to metaphysics, its intent attention not just to surface reality but to what might lie beyond it, gives us cause for calling it the Age of Concentration.” Suggesting that each new historical shift is meant to solve a specific social problem, Vodolazkin argues that the modern world overemphasizes surface, progress, data, and individualism over depth, the eternal, wisdom, and community. “As the rights set down for the individual multiply,” he continues, “a turn is inevitably coming for a right to cross the street against a red light. Because our concept of rights is antihumane at its core, it activates the mechanism for self-destruction. The right to suicide turns out to be our most exemplary liberty.” He goes on in the second essay, “The Age of Concentration,” to explore how the notion of social “progress” is uniquely tied to the horror of utopianism, writing that “at the very essence of a utopia is the idea of progressive movement toward a not-yet-achieved perfection.” This might at first glance seem only tangentially related to the work of Solzhenitsyn, but these are in fact the very same issues — the spiritual emptiness of secular humanism, the appeal and the danger of utopian ideology — that Solzhenitsyn wrestled with.

Another standout essay is David Walsh’s “Art and History in Solzhenitsyn’s The Red Wheel.” Focusing again on Solzhenitsyn’s interest in ideology, Walsh writes that “the protagonists of ideology are driven by the conviction of the superiority of their conception to all that has existed. The servants of truth subordinate themselves to what is required to bring what is already there more fully into existence.” Solzhenitsyn, Walsh reminds us, wasn’t just interested in avoiding the hubris that comes with ideological certainty; he also encouraged people to play an active role in the recovery of the complex world. Art, like spirituality, is a great way to cultivate a sensitivity to the vast depth of reality. Like the spiritual, art exists above history. Walsh explains that “art surpasses history by penetrating to what history has yet to discover within itself. The truth of art is the truth towards which history converges.”

Solzhenitsyn and American Culture could serve as an introduction to the writer’s literary work, as a kind of traveler’s guide read before vacation. Or it could be a valuable addition to the nightstand of anyone interested in deepening their knowledge of Solzhenitsyn. The book’s ultimate significance, however, is spiritual. In following Solzhenitsyn’s intellectual footsteps, in taking up his preoccupations with ideology, art, morality, and meaning, the book makes Solzhenitsyn himself into a passageway through which we glimpse the universal. Or as Nathan Nielson puts it, “We gaze at the universe through the Russian navel.”

In taking this narrow passage through the particular toward the eternal, we begin to understand Russia as it exists beyond its creepy contemporary politics or the occasional moral failures of its culture and instead see it as a complex and occasionally even contradictory civilization-state. But it also helps us to see ourselves and America more generally in the same redemptive light. We can’t control the patterns of history, only act appropriately within them. As Miles Davis said, “It’s not the note you play that’s the wrong note. It’s the note you play afterwards that makes it right or wrong.” In this sense, Solzhenitsyn and American Culture doesn’t just talk about spiritual community but might even act as an aid in its realization. The song is unfinished, still playing and changing, always waiting for the next note to be played. And there’s always a chance that the Russians and American soldiers fighting at the club might embrace and begin dancing together. I’ve seen it happen.

Scott Beauchamp is an editor for Landmarks, the journal of the Simone Weil Center for Political Philosophy. His most recent book is Did You Kill Anyone?