The practitioners of the contemporary American novel, mostly residing in coastal cities and hoarding graduate degrees, produce books about “important” subjects such as climate change and systemic racism. This is why Adrian Nathan West’s debut novel, My Father’s Diet, detailing the degradations of small-town life in Nowhere, USA, is such a delightfully radical read. When most authors self-consciously look to expand the scope of their books in the hope of creating a cringey multigenerational saga for the book club crowd or a novel that speaks to the “current political condition,” West, an acclaimed translator of more than a dozen books, has gone the opposite route: My Father’s Diet is a small book about small lives. In his devotion to the complexities hidden in the smallness, West has written a deceivingly grand novel about the forgotten blue-collar Americans who toil obscurely away.

The landscape is an unnamed town in Middle America, and our guide is a dispirited and dulled young man coming of age whose father “moved to the Midwest to make something of himself.” The father bolted when the son was 2 years old and has been in and out of his life ever since. Now that his failed ramblings have left him unfulfilled, and with his kooky wife in tow, he reappears in town. The son, who’d gone away for college but is back home after failures of his own, is afflicted with a bottomless male malaise. The young man and the middle-aged man reconnect — not because they desire some great reconciliation, but because they don’t have much else going on. The bulk of My Father’s Diet depicts the budding relationship between father and son and how disparate views on masculinity shape their respective identities. But the novel is about much more than the contemporary male condition in a decaying America. The men in the novel are certainly broken, but so are the women, such as the father’s wife, Karen, who opens up a spirituality/self-help center called CESID (Center for Emotional, Spiritual, and Intellectual Development) on a whim after her job as a healthcare aide providing “home health care for those too poor, too ill, or too obese to travel into town” proves unfulfilling. The main thread that unites the characters in My Father’s Diet is the profound feeling of unfulfillment that afflicts most downwardly mobile people and how every waking moment is a constant battle against the malaise brought about by living in the fringes of a sputtering empire.

What passes for inner peace in the novel isn’t found in characters who lean into cooked-up spirituality like Karen — she ends up having a near breakdown — but in someone who calls himself The Weirdo, the son’s stepfather, a man who “had no box or file folder containing birth certificate, tax returns, or any other documents bearing indications of his past or provenance.” The Weirdo, along with the dishwashers who work with the son in a ramshackle restaurant, and his mentally ill aunt with “dappled skin like a withered fruit” who “seemed never to pass into adulthood” have begrudgingly accepted the unfulfillment that doesn’t result in happiness but in an indifferent acceptance of their low-down plights. These beaten but not defeated — you need to care to be defeated — losers aren’t punching back at life. They are merely dodging punches and looking to avoid the inevitable haymaker that puts them out of their misery.

The unfulfilled characters running out the clock on their lives and the sense of blue-collar despair that permeates My Father’s Diet situates the novel in a dirty realist style, a la the works of short-story masters Raymond Carver and Richard Ford, a style that has fallen out of fashion in recent years as literary fiction trends toward the overtly political. This is a throwback novel that hark back to the 80s and 90s when dirty realism, trafficking in seedy depictions of mundane life, ruled the literary world and stories about the working class drifting aimlessly through their lives weren’t met with derision from publishing gatekeepers. It’s no surprise, then, that My Father’s Diet, a novel totally antithetical to the literary zeitgeist and one that mucks around with forgotten people, is published by a small press. But once again, the smallness of this novel and the smallness of the lives contained within are what make it such a depressing pleasure to read.

West makes adept stylistic choices that heighten the blue-collar despair he’s going for, such as never quite grounding the reader in a distinct location. Characters go to Atlanta and “out west,” but most of the novel takes place in a purposefully anonymized Middle America town. A reader can pinpoint the exact setting, if need be, but the novel is less about a certain location than the brokenness and despair that has overtaken regions of America known as “flyover country” and the like. The father and the son can be any father and son, and the town is no town at all, which is to say that it’s every town. This is the disappeared and forgotten America of gun stores and pawnshops and independent wrestling shows — the grotesquely beautiful American sameness of it all.

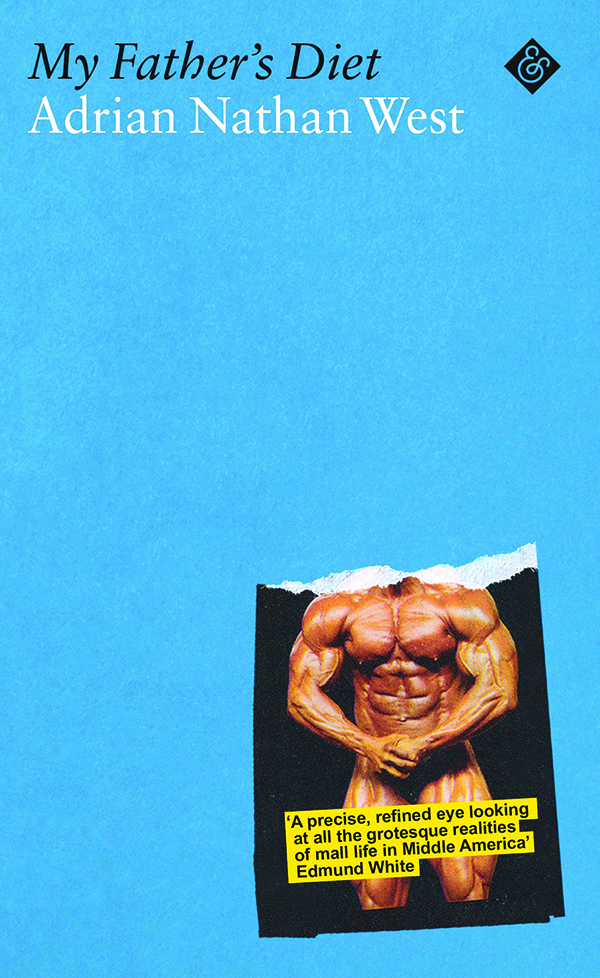

The son, who spent his days when he was away at college “walking the grid of streets between the town and the river, anticipating poetic or philosophical inspirations to be jotted down in his leatherette pocket journal,” grasps for solidity in intellectual pretensions. But the father, 55 and long betrayed by the affected intellectualism of his youth, chooses to make himself physically solid: He will compete in a bodybuilding contest in the hope of winning the “Body You Choose” competition put on by Total Body Development magazine. It’s the age-old story of a man trying to transform his body in order to become a new and better version of himself, but in West’s capable hands, this borderline cliche conceit works. The dispassionate son agrees to help the father, even working out for a day alongside him with a crazed bodybuilder predictably named Gunn. What ensues is not quite a coming of age in which two bruised men are brought together by mutual struggle, but a tenuous understanding that one day might blossom into something deeper. Still, from where they started, two disconnected and aimless men, this flimsy connection between father and son is as great a victory as possible in the broken vision of Americana that West has built.

Recent novels, including Sean Thor Conroe’s Fuccboi and Atticus Lish’s The War for Gloria, have dealt with the condition of American masculinity. But where those books dive headlong into the political, My Father’s Diet, so limited in scope, and so intimate, tackles the daily debasements and intricacies of the male condition in a manner that is far closer to reality. Nothing much happens in a man’s life outside of the quiet indignities he must bear on his own, and even when something does go down, such as a bodybuilding contest you quixotically enter, the end result doesn’t matter much anyway. Which is why we never find out if the father, after weeks of working out and eating copious amounts of protein and even taking steroids, wins the competition. He sends in the pictures of his tanned and ridiculously glistening muscle-bound middle-age physique to the magazine, and that’s that.

My Father’s Diet is a slim and acidic novel that doesn’t quite fit in today’s literary landscape. But thankfully for the few readers left who enjoy mucking around with the lost losers of America, it exists.

Alex Perez is a fiction writer and cultural critic from Miami. Follow him on Twitter: @Perez_Writes.